HOME > Japan SPOTLIGHT > Article

Future Prospects of Geopolitical Risks: Adapting to the New Normal Era

By Keiichiro Komatsu

2016 was a year of dramatic change. Brexit and the election of Donald Trump were seismic events that will have long-term influence.

In June, the British public voted in a referendum on the question of whether the United Kingdom should stay or leave as a member state of the European Union, and surprised the rest of the world by deciding to leave. Then in November, Trump, a presidential candidate from a purely business background, as chairman and president of the Trump Organization, who had already surprised the world by winning the competition within the Republican Party nomination, did so again by beating the Democratic Party candidate Hillary Clinton.

In December, the Italian public voted in their referendum and rejected a constitutional amendment. This means that the euro currency is likely to eventually face another crisis as the majority of bad debts in Europe are from Italy. Various elections in Europe this year put the concept of the EU as well as its future under scrutiny. The extremely large numbers of refugees, mainly from the Middle East and Africa, flowing into Europe, particularly since the summer of 2015, also contributed to the UK referendum result and other countries' tightening of borders, against the idea of a borderless Europe. Within this context, this paper discusses the new challenges for the international community and the prospects for 2017 and beyond.

In addition, this paper will also try to offer some ideas to help deal with these challenges.

What Is Behind Brexit and the Trump Phenomena?

What we have already learnt from 2016 is that these changes bring, in the immediate short-term, i.e. on a weekly basis, noticeable fluctuations in the markets, including stock and currency markets. On a monthly basis, however, the world economy has shown toughness and has recovered. Yet, on an annual basis, structural changes are taking place and such political events will have further impacts. Trump has said that there will be great changes to the EU concept and the euro in the future. German Chancellor Angela Merkel and French President François Hollande deny such a prospect. Some observers say that it will be business as usual. Some say that the euro is finished. Whatever happens, we should brace for significant changes in coming times.

In this context, one should pose the question: do terms like nationalism and populism accurately express the nature of support behind Brexit and the election of Trump? For the older generations, the concept of a single market in Europe under the EU is a relatively recent one, coming in the wake of repeated great wars particularly between France and Germany. The goal to establish a "United States of Europe", uniting France and Germany as one country was symbolic of a new sense of values born after two World Wars.

However, for the new generations who have only seen the deepening of integration of the EU during their lifetime, the EU is already the status quo. In this sense, if one simply thinks that the younger generation is in support of the unification of Europe and globalism more than the older generation, this probably overlooks the difference between the richer educated class with the tendency of being pro-EU, and the less well-off supporters of Brexit among the younger generation. By the same token, those who are highly educated and relatively rich are believed to have favoured remaining in the EU even among the older generation. Under the current structure of the EU, the rich, educated urban population have benefited from EU membership while those who are less well-off, uneducated, and/or live in rural areas have felt rather victimised by the EU.

Urban businesses have benefited from economies of scale in the larger united EU market rather than a one-country market. In contrast, small enterprises and family businesses could not benefit from economies of scale and have been rather overwhelmed by large businesses coming freely from other EU countries. If one is highly educated and achieved a higher level of education, such as lawyers or accountants, or medical doctors, then one can operate anywhere in EU member countries. In contrast, those without a high level of education and qualifications, who merely operate small businesses locally, have not felt the benefit of membership of a larger EU market.

The principle is simple: people favour what they can benefit from and dislike what they see as putting them in a disadvantageous situation. This principle is a more important factor than the generation gap. In this sense, the gap between the rich and the poor, highly and less educated, those benefiting and those who feel they are not, divided and polarised the UK. This same principle may divide and polarise other countries in Europe as well. What this means is that the accumulated frustration was expressed at the polls by people who felt left behind and this voice became the majority. In Trump's case in the United States, there are also clear divisions between voters from the urban and rural areas corresponding to Trump and anti-Trump.

An Era of New Normal

At this point of time in early 2017, it is difficult to foresee how the future will unfold as we have entered uncharted waters. What is clear is that this new era will be of continuous dramatic changes, and that would become the "New Normal". To understand the background of the current international state of affairs, one needs to look back at the following developments that have been particularly significant over the last several years (Table 1). What is the common thread among these events? It is anti-elitism, and more accurately, anti-establishment and anti-status quo.

First, in the Middle East, the regimes of former President Zine El Abidine Ben Ali in Tunisia and President Hosni Mubarak in Egypt were condemned as dictatorships after the outbreak of the "Arab Spring". At that time, many Western countries both in Europe and North America as well as the global media internationally supported the uprising of anti-government protests as democratic movements. However, the ways in which the governments were overthrown by these movements were technically illegal and very violent.

For instance, the author personally knows some cases where family members of senior Tunisian officials were attacked by protestors at home while the officials were away. Their homes were destroyed and burnt down. Their wives and small children were taken somewhere against their will and disappeared. These series of incidents were not widely broadcast by the global media.

In fact, the governments were not changed through democratic elections as they should have been. Yet the international community still supported these movements as democratic. Taking the case of Libya, some developed countries led by the UK and France even used their air forces to conduct military operations (in reality in support of anti-government movements against the then Muammar Gaddafi regime). This resulted in the overthrow of the government without democratic elections.

With the "Arab Spring", even when one could understand the feelings of people who were fed up with their existing governments and wished to change them, it was technically still illegal and a violent way of taking down a government. Thus, a serious question arose: whether an illegal and violent overthrowing of internationally-recognised governments could be justified by the international community or not.

Another serious question that arose was whether intervention in internal affairs this way is acceptable or not. Furthermore, even if this could be justified, legally-speaking, where is the consistency with the principle of the respect of the Rule of Law? In fact, before the massacres occurred in Bosnia, Rwanda and other places in the middle of 1990s which attracted significant attention from the international community, it was conventional understanding that intervention in internal affairs was illegal.

Even if intervention in internal affairs could be justified as international responsibility to protect the victims of a dictatorship, the definition of dictatorship itself and who should judge a government as a dictatorship have been questioned and there is no clear consensus yet. At present, responsibility to protect is not international law.

These issues have caused several confusing international affairs in recent years. For instance, President Vladimir Putin of Russia later pointed to this Libyan intervention case when the West imposed sanctions against his Russia after his military occupation and eventual annexation of Crimea in 2014. In fact, the West has not been successful in convincing the majority of the Russian population who have supported Putin's annexation of Crimea.

In the same year, the Islamic State (IS) finally caught the attention of the international community when its fighters occupied Mosul, one of the largest oil and gas fields in northern Iraq. Not only personnel in the international energy sector, but also experts in security became worried about the possible influence of IS occupation of the region on international affairs.

Soon after IS fighters crossed the border from Syria into Iraq and captured Mosul, IS denied the border between Syria and Iraq. In fact, some independent observers have seen the border as unrealistic considering the region's social and political situation around the border areas. The people that inhabit northern Syria and northern Iraq are several tribes of the same Sunni Arabs.

The Bashar al-Assad regime in Syria has been perceived by many as a Shia-dominated government, although Assad's Ba'ath Party is originally Arab socialist which used to be against religions including Islam. This is very close to how the Ba'ath Party under former Iraqi President Saddam Hussein was.

The regular army under the Assad regime was made up of conscripts. After the outbreak of civil war in Syria, the Alawite fighters began to dominate the Assad army. Then most conscripts from different religious factions left the army. Since the Alawites are a minority population in the country, they fear losing power if a democratic voting system is introduced. What has been overlooked is the fact that Alawites have been questioned among Shias in the regions if they are actually part of the Shias. This might be a significant factor when trying to assess the distance between the Assad regime and the Shia state of Iran are in the geopolitics of the region. Nonetheless, international observers and most of the media have tended to see Alawites as Shias.

In any case, the Assad regime is not seen as an ally by the Sunni Arab tribes; rather, the tribes have felt suppressed by the Assad regime through the civil war since the "Arab Spring" began. In Iraq, after Saddam Hussein's government was overthrown, a Shiite government emerged in Baghdad since the majority of the population in Iraq are Shias. Consequently, as long as so-called democratic elections continue to establish the central government in Baghdad, the Sunni population who inhabit mainly the north and west of Iraq have no hope of coming to power again in the future. This is exactly what the Alawites in Syria fear and why they support Assad. These factors fuel the bond between Sunnis in Iraq and Syria, who tend to be in support of the Sunni militia called IS.

The Syria-Iraq border is legal in the sense that it has international recognition. However, some observers have questioned the legitimacy of the border on the basis of the historical fact that it was drawn under the secret Sykes-Picot agreement between British and French officials during World War I. When IS denied the border, it cannot be refuted that those factors contributed to attracting relatively wide support from the local Sunni-Arab tribal powers. Thus, the challenge against the status quo by Sunni groups in the region is one side of the conflict in the Middle East.

More than 15 years have passed since the declaration of the "War on Terror" in 2001 and more than six years since the "Arab Spring" began in 2010. The sad fact is that none of these countries Tunisia, Egypt, Libya, Syria, and Iraq in addition to Afghanistan, have yet become reasonably stable.

Terror attacks have actually been increasing not only in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA), but also in many countries in the West. Taking 2015 and 2016 alone, repeated large-scale attacks occurred in Paris, Brussels, Nice, Berlin, Munich, Istanbul, Cairo, Baghdad, Jeddah, Medina, Jerusalem, Dhaka, Bangkok, Jakarta and other places by many militants, and intelligence personnel. Terror attacks will expand exponentially unless the root causes and the sense of injustice in the world are tackled and mindsets changed fundamentally on all sides.

Under these circumstances, the threat of weapons of mass destruction (WMDs) is becoming more realistic and significant. If anyone eventually uses WMDs, they would most likely be biological weapons and possibly chemical weapons rather than nuclear. Biological weapons are also known as "WMDs for the poor". This is because of the extremely low cost of production and the ease of carrying them.

Furthermore, cyber wars are already taking place. For instance, the most recent controversial issues of fake news and hackers, including those carried out by Russians during the US presidential election campaign.

Repression by Force of Occupy Movements Around the Globe

Following the "Arab Spring" from December 2010, anti-inequality movements spread across the world in 2011 (Map 1). These were known as "99% vs. 1%" movement or the Occupy Movement (Photo 1), with the slogan "We are the 99%".

In fact, especially since the end of the Cold War in the early 1990s, global inequality has increased rapidly. It was claimed at the time of the 99% vs. 1% movement that the top 1% hold 40% of the world's wealth. Thus, frustrated protesters' anti-status quo sentiment was observed in many countries. However, although it attracted a significant number, it did not necessarily draw the vast majority. The sheer scale of such movements divided people.

Globally, the authorities used force to repress those movements and it became temporarily quiet for the next couple of years.

Scotland, Corbyn, and Trump

Then in 2014, the people in Scotland went to the polls and expressed their will through the ballot box, instead of protests on the street. A significant number voted in support of Scottish independence from the UK, many of them motivated not only by Scottish nationalism but also by anti-status quo sentiment towards the government in Westminster. The rest of the world who did not understand the anti-status quo feelings in Scotland was surprised by how far the independence movement had come and then were relieved to find that a majority of 55% voted in favour of remaining in the UK.

However, some observers pointed out to the author that roughly up to half of the population in Scotland are historically of "English origin", and well over the majority of those of "Scottish origin" were in favour of independence. Regarding the issue of Scotland, another referendum on Scottish independence could be on the agenda again depending on the outcome of the coming Brexit negotiations between the UK government and the EU authorities in Brussels. This is because the majority of Scottish people who voted, voted to remain in the EU, in contrast with the majority in England who voted to leave. Thus, both the Scottish independence movement and the Brexit decision have divided people.

Of course, there was no violence in Scotland, and democratic and legal procedures of voting were held. The means of IS rising has been violent, and this is a decisive difference between the two cases. Yet, when the author talked with some observers in the UK, they said that there is something in common between what Scotland and IS are trying to achieve. The common thread is that Scotland and IS are both trying to redraw established borders and create new states. What the establishment does not like is the ease with which they are both trying to establish a new country/state, redefining the norm.

Then in 2015, far-left MP Jeremy Corbyn was elected as the leader of the British Labour Party. His position was distant from the then status quo that was established by former Prime Minister Tony Blair's New Labour (moving closer to Conservative policies). Corbyn emphasised the importance of renationalising some industries and he is also known for his Euroscepticism, in contrast to both then Prime Minister David Cameron's Conservative Party and Blair's New Labour, which have pursued privatisation and globalisation as major parts of key policies. Corbyn's victory surprised many, and his views have alienated some party supporters as well as members of his own parliamentary team, leaving the Labour Party in a state of some turmoil.

Then the American presidential election campaign followed. Bernie Sanders, a Democrat candidate considered to be from the left emerged to compete against an established lawyer and former First Lady Hillary Clinton for the Democratic Party nomination. This was while on the side of the Republicans, Trump emerged with his series of unusual speeches based on his successful experience as a businessman, not as a politician. Neither Sanders nor Trump were perceived to be from the political establishment in Washington, DC.

Eventually, Trump was elected as the 45th US president in November 2016 and inaugurated on 20 January 2017. Both Sanders and Trump attracted significant support from people who were fed up with the status quo which resulted in dividing the members of both parties and even the whole of the electorate in the US. Thus, these events in the last several years have shown a global tendency that at a popular level roughly half of the population voted against the status quo.

What one can see in these developments is that around half, sometimes the majority, of the voting population of many countries have felt elite-tired, more accurately establishment-tired, and wanted new and fresh faces. Not only people from the bottom of the income scale who might have been desperate and seeking great changes to the current situation, but also many from the rest of the population voted for the new norm.

For free competition to function properly in the social structure of capitalism, people need to be able to start from the same line. Of course, this does not necessarily mean that people need to start from the same living standard. But they should be given equal opportunities or at least opportunities within a range that enables those at the bottom to catch up with those at the top through reasonable efforts.

In fact, the real issue occurs when people start to lose hope that their living standards will continue to worsen no matter how much they try. In such a situation, extremism could emerge everywhere and form a threat in the coming years. What is important is finding ways to narrow the gap in opportunities rather than the gap in living standards. To make capitalism function effectively with free competition, guaranteeing delivery of equal opportunity is necessary. Otherwise, it does not work if people are already divided at the time of birth.

Trying to find a universal level that fits all countries is futile as different fluctuating factors such as price indexes, exchange rates, assets and income flow levels, and employment rates all affect the right level for each country at any given time. It is somewhat similar to the problem of the global poverty line. When social and economic factors differ significantly by country, the global poverty line can lead to misleading policies. It is important to try to minimise unreasonable gaps based on the social norms of each society. What is acceptable in some societies would not be acceptable in others, and thus discussions must take into account these social norms, rather than simply setting so-called global and/or universal lines.

The Nature of Conflicts in the Age of New Normal

Conflicts today involve sudden bombings and terror attacks out of the blue. Even if you sense that something might be coming, things remain peaceful until it actually happens. Moreover, asymmetric warfare is already the norm, and future wars are more likely to be fought through terror attacks and guerrilla warfare.

In January 2009, the author was in the outskirts of Antananarivo, the capital of Madagascar, visiting a national park to see the lemurs. For those who do not know, Madagascar is a huge island country in the Indian Ocean next to the African continent. While there were rumours that a coup d'état could take place at any time, it was a very peaceful day. On the way back to Antananarivo, the author saw anti-government forces already putting up barricades. Yet the atmosphere was still business as usual with families and children walking past as if there was nothing different.

The next day, smoke was breaking out all over the place (Photo 2). From around noon, the demonstrations became violent and a section of the military called CAPSAT started to revolt. Suddenly, a coup d'état was taking place. Because it was so calm the day before, it didn't feel very real. It was such a great pity because the so-called "coup business" in Africa had looked like it was dying down for nearly a decade, ever since Nigerian President Olusegun Obasanjo successfully managed a change of government through democratic elections rather than by an illegal and violent coup d'état. Now a small part of Malagasy troops, CAPSAT, was resuming the coup business. The author strongly felt that if the international community allowed it to happen easily, it could spread like an epidemic again.

Before the coup, his role as special advisor to the president of the Republic of Madagascar was to advise on economic policies to lift the national economy through trade and investment promotion. This included not only advising but actually making it happen by finding, bringing and assisting investors. However, his role had to change to a highly diplomatic one where he and his colleagues made their very best efforts to re-establish a legitimate government in the country. Fortunately, in 2013, a democratic election was eventually held in Madagascar and a new legitimate government established. As Raj Makoond, a leading businessman from neighbouring Mauritius, eloquently put it, one should not underestimate the stability factor and must find ways and means to include conflict prevention components at the very outset of a development strategy.

In fact, the author had worried during the Malagasy coup that this could spread. Indeed, the "Arab Spring" began in 2010. Just like the case of Madagascar, it was not only illegal and violent but also sudden. The development and expansion of technologies and sales of radio, mobile phones and ICT made this possible. Indeed, these new technologies made it easier for anti-government groups to organise such demonstrations.

The following year, in December 2010, the author was in Tunis attending an international conference on economic co-operation between Japan and the Arab League. The conference ended with great success. Tunis seemed so safe and peaceful. A few days later, the author was still in Tunisia when suddenly the "Arab Spring" broke out. Tunis was plunged into a conflict triggered by self-immolation. President Ben Ali was ousted, and Tunisia has been in a situation close to internal conflict ever since. This spread to Egypt, Libya, and Yemen, where long-standing regimes lost power.

Recognising geopolitical risks in the years ahead, as mentioned above, this paper will now propose an idea that might hopefully lead to a solution.

Shifting Centres of Economic Growth

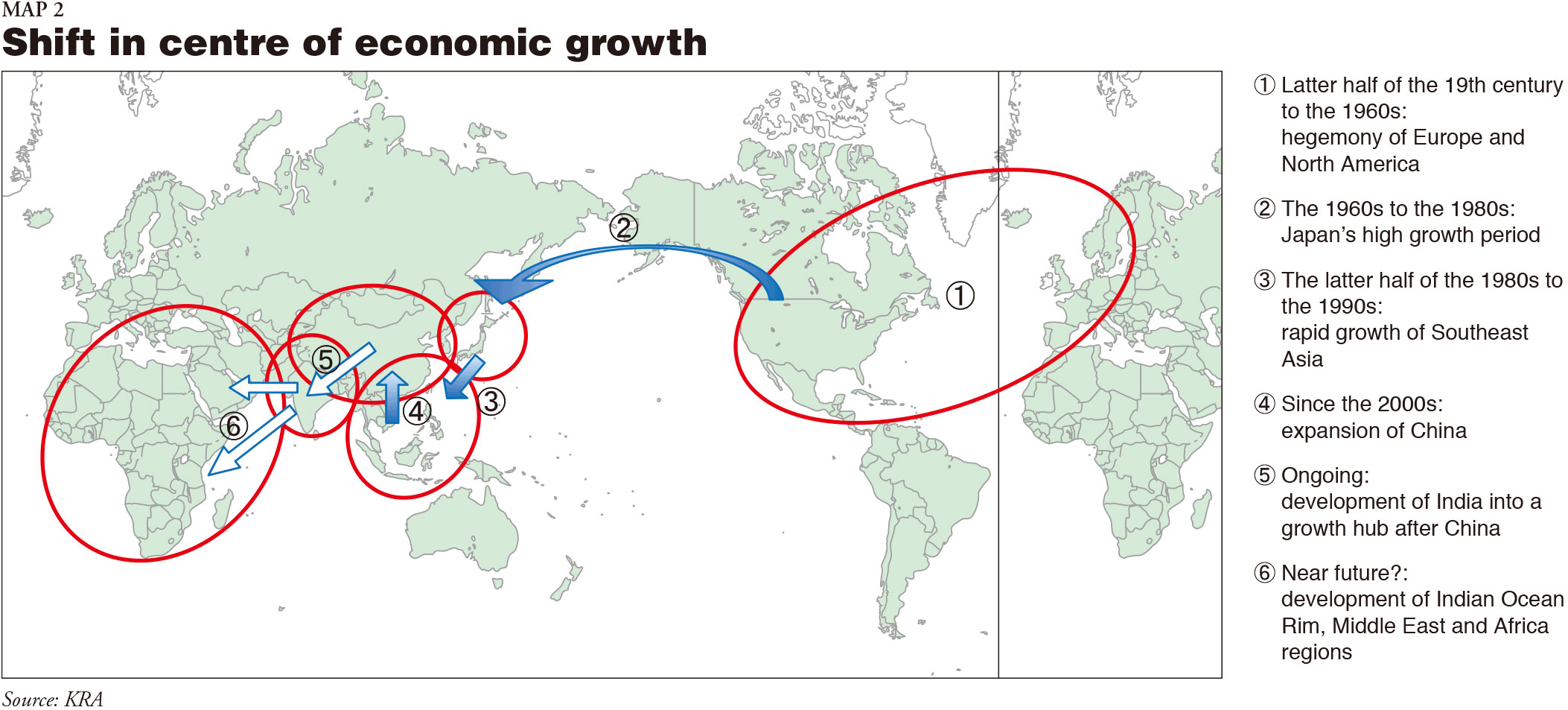

To understand the background of the idea, one needs to first look back at the historical development of economic growth in the international community. Modern industries began with the Industrial Revolution in Britain from the middle of 18th century. Looking at the centre of world economic growth in the timespan of decades, we can see that it has been shifting geographically from "east", starting from Britain westwards to North America and on to Asia, against the conventional image from the "West" to the "East" (Map 2). It is also noticeable that the total GDP of developing countries has started to overtake that of developed countries with the emergence of markets such as BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa). This suggests that the Northern Hemisphere-centred approaches need to change.

When we look at the demographic structures of countries around the world, developed countries including Japan are becoming increasingly ageing societies with a combination of longevity and low birth rates. There is a concern that this might hinder future economic growth as the young population, the main source of labour, is in decline. Even among the BRICS, the young population is either already decreasing or not increasing, showing signs of ageing societies. In contrast, some countries in the Middle East and many in Africa have a constantly growing young population. This means that developing countries in the Middle East and Africa have the potential to become the driving force for future global economic growth.

However, for that to happen, it is not sufficient to simply have a growing young population. They need to be in work. If they can find or create jobs in which they can find meaning and a sense of purpose, they can become a major driving force for the world economy. Otherwise, they may find meaning in extremism, leading to destabilisation and destruction.

It is therefore vital that there are jobs for the youth in the Middle East and Africa. It is here that the Japanese experience may provide a hint. Chart 1 shows the growth rates of East Asia and the Pacific, Sub-Saharan Africa, and low-income countries. Whilst Sub-Saharan Africa's growth rate is low and unchanging, that of East Asia and the Pacific shows rapid increase since the mid-1970s. The widening of the gap between the performance of East Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa is shocking.

As Chart 2 shows, this increase corresponds to the "four waves" of Japanese trade and investment into Southeast Asia and the Pacific region. The entry of Japanese companies and inflow of Japanese investment into this region contributed significantly to the lifting of their economies. The four waves into Southeast Asia are since 1971, since 1979, since 1985, and since 1995. This has sometimes been called a "happy marriage" between Japanese industries and Southeast Asia.

It may be useful to analyse and learn from the "happy marriage" experience of Japanese and East Asia and Pacific industries, in order to try and recreate a similar experience in the Middle East and Africa.

Observers who have experience in working with Japanese businesses often comment on the Japanese "obsession of distance". Practically, geographical distance is the largest hindrance for Japanese industries. The recent developments in ICT and transport capacity with new technology are helping to reduce this distance. However, it is still not enough. In the author's view, this physical distance can be bridged if there is a foothold in the Indian Ocean with the long-term vision to create a larger regional market that connects the Middle East and Africa with the Asia-Pacific regions through the Indian Ocean (Map 3).

The Indian Ocean is geographically and culturally the meeting point of Africa and the Asia-Pacific region. While the Pacific Rim economic zone with APEC is well-developed and functioning, the Indian Ocean rim economic zone is still in a much earlier stage, and thus developing the region is an urgent mission.

In this context, an important development took place in the summer of 2016. For the first time, the Sixth Tokyo International Conference on African Development (TICAD VI) was held outside Japan on African soil. Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe announced in Nairobi that "Japan bears the responsibility of fostering the confluence of the Pacific and Indian Oceans and of Asia and Africa into a place that values freedom, the rule of law, and the market economy, free from force or coercion, and making it prosperous." The uniqueness of TICAD VI is that despite having "Tokyo" in its name, its emphasis is on multilateral co-operation and connecting the Asia-Pacific region and Africa through the Indian Ocean. It has the possibility to initiate a potential Asian economic miracle in the Middle East and Africa in order to lift the region's national economies in a sustainable manner.

Increasing economic co-operation including public sector aid and private sector trade and investments in the Middle East and Africa from developed countries will be one of the means to overcome the coming difficulties and create prosperity for the world economy in the future. The key is to make sure aid and investments are used in a manner that lifts the whole national economy of the receiving country and to provide equal opportunities for the population. If only certain sections of the population benefit in a manner that merely increases inequality, the aid or investment will eventually lead to social instability.

Conclusion: Change, Not Crisis

What we have seen is that there are two opposite forces in recent international developments. On the one hand, there are forces for the disintegration of the current status quo, such as independence from the EU or individual countries. On the other hand, globalisation is likely to continue due to improvements in infrastructure and communication methods. Caught in the middle between these two forces, we need to start to reconsider formerly taken for granted notions like the nation-state. We also need to reconsider the directions of economic policies to make the Middle East and Africa the driving force of the world economy and not a centre of instability.

As early as the spring of 2011, when the then British Prime Minister Cameron made the decision to use military force against Gaddafi in Libya, the author's former supervisor Wilfrid Knapp, emeritus fellow at the University of Oxford and expert on international relations, said "Cameron does not know what he is doing. We are heading towards a Third Word War." He mentioned this sense of crisis to the author, and said such a war is going to be similar to World War I and World War II in that people will be fighting "everywhere" across the world, but the difference would be that guerrilla warfare and terror attacks would increase rapidly and that politicians and historians will not be able to define when it started and ended. It is likely to go on forever and must be stopped.

Those were the last words of Wilfrid Knapp. Usually he suggested solutions, but this time he didn't.

The international community will have to come together to invest in developing countries in a manner that lifts the national economy of each country and provide hope for the people in the regions. It is time for all to seriously come up with some solutions.

The author looks back at this supervisor's words mentioned above and is afraid that what he said is happening. This paper urges all those readers who are concerned with these matters to discuss and co-operate to overcome the coming difficulties.

As one does this, it is necessary to change the present mindset of seeing those political events as changing times rather than merely as crisis. That way, one can focus on adapting our way of thinking and treating those changes as opportunities. When living in turbulent times, one must not wait for the storm to pass, but learn to dance in the rain.

Japan SPOTLIGHT March/April 2017

(2017/03/14)

Keiichiro Komatsu

Keiichiro Komatsu (D.Phil. in International Relations, Oxon) is principal at Komatsu Research & Advisory (KRA) and an expert in business promotion and country-risk analysis. He has worked at the Japanese Central Co-operative Bank for Commerce and Industry, the World Bank, the British government (seconded by JETRO) and Madagascar government as special advisor to the president of the republic.

Japan SPOTLIGHT

- Coffee Cultures of Japan & India

- 2025/01/27