HOME > Japan SPOTLIGHT > Article

Trump 2.0 Unprecedented High Tariffs Policy & Responsive Navigation of East Asian Economies

By Choong Yong Ahn

Introduction

The 47th US President Donald Trump has virtually ended the free trade era which has prevailed since the end of World War II, and which has contributed to global prosperity and growth. In his inaugural speech on Jan. 20, 2025, he declared "America will soon be greater, stronger, and far more exceptional than ever before." In this context, he introduced a high tariffs policy against all US trading partners and higher tariffs against all trading surplus economies, and exceptionally far higher tariffs against China. Trump's rhetoric and actions have further strengthened his transactional view of international relations that he laid out during his first term of presidency.

With these unprecedented high tariffs policies, far stronger and more swiftly implemented than during his first presidency, the Trump 2.0 economic policy package also include a major corporate tax, the deportation of illegal immigrants, and a consequential strong dollar. During the election campaign, he made clear that he would adopt these polices to create jobs and protect American industries, preaching his touted slogan to "Make America Great Again".

Calling "tariff" the most beautiful word in the dictionary, Trump proposed an unprecedented tariff hike on all imports universally and additional 10% tariffs on top of the current rate of 50% on imports from China, as well as resorting to reciprocal tariffs on the trading surplus economies with the US. Likewise, he will put "America First" in dealing with all US international relations.

Under this protectionist doctrine and amid an acute high-tech rivalry between the United States and China, East Asian economies--and for that matter, the rest of the World--are facing unprecedented challenges, as the geoeconomic fragmentation already underway becomes more aggravated. From now on, trade protectionism may appear to be a rule rather than an exception. As a result, the multilateral WTO system is being pushed helplessly into demise.

Against this backdrop, how should East Asian economies respond to ensure their own robust growth and continue to engage in international trade, individually and collectively? During the past decades, East Asian economies have been increasingly intertwined through supply chain linkages in an open trade regime, especially after China's entry into the WTO in 2001. Most smaller economies in the region, significantly dependent on the two largest economies in the world, the US and China, seem at a loss how to navigate the direct impacts of both Trump's protectionist policies and the potential fallout from aggravated US-China trade warfare. I will attempt to answer some of these questions.

Economic Effects of Trump's Policies on US Economy

On April 2nd, Trump unveiled officially his "liberation day" tariffs to impose a baseline tariff of 10% on foreign imports across-the-board. He further charged larger reciprocal tariffs for those trading surplus economies with the US. For example, 20 % for the EU, 25 % on Mexico and Canada, 34% on China, making total tariffs of 65-70 % including levies from the previous administration, 46% for Vietnam, 32% on Taiwan, 26% on South Korea, and 24% on Japan, raising the weighted average tariffs to 23%.1 Trump leverages "tailor-made trade deals" with individual countries. He also charged 25% tariffs on imported vehicles and parts starting April 2, 2025. Tariffs are the central part of his economic policies. He firmly believes tariffs will boost US manufacturing, and protect jobs, as well as raising tax revenues and growing the US economy.

The rationale behind Trump's policy is that the high tariffs will lead to an increase in demand for domestic products made in US and a consequent recovery in US manufacturing. The ultimate purpose of the high tariffs policy is to induce "reshoring" of domestic and foreign firms into the US for growth and job creation. However, the commitment both to eliminate trade deficits and to pursue foreign investment shows the inconsistency of this policy. Trade deficits and capital surpluses are two sides of the same coin, and this causes unpredictability in the business environment for American and foreign multinational companies.2

Trump's rapid-fire tariffs policy is generating serious uncertainty that could weigh on businesses and household spending. Some pundits have even marked up the chances of a recession.3 Mainstream economists believe Trump's high tariffs policy on imported goods and consequent US consumers' higher demand for domestic goods, with reduced foreign imports in a full employment economy, will exert upward pressure on prices. Then, to keep inflation under control, the Federal Reserve will have to increase interest rates. As a consequence, the US dollar will get stronger, and US exports will suffer. The trade deficit cannot be improved in this way.

In addition, China and European nations are determined to respond with tit-for-tat retaliation, and then the outcome would be even worse for the US as well as its trading partners. Sluggish American exports and little improvement in the trade deficit, if any, are likely to lead to higher inflation and an economic slowdown in US.

As another policy pillar, Trump has promised to extend the tax cuts enacted in 2017. The corporate tax rate, which was reduced from 35% to 21% in 2017, will be further cut to 15% to help American businesses, especially manufacturing firms. Furthermore, Trump has promised to deport illegal immigrants, numbering around 11 million, and may deport about 1 million a year. Total US employment is 160 million. Job vacancies are inevitable in labor intensive service sectors.

From the first Trump administration, the lesson one can learn is that the level of national savings, which falls short of the investment level, determines ultimately the trade deficit. The proposed tax cut will cause the national savings rate to fall and thus increase the budget deficit. So both budget deficit and trade deficit would widen on a greater scale than before. With these negative outcomes, many critics of Trump's high tariffs policy argue that it will benefit other countries--making "America Last" rather than "America First".4

Some argue that Trump is using tariffs as a tool to achieve other policy objectives in international deals. For example, his punitive tariffs on China and delayed tariffs on Canada and Mexico are aimed at getting America's biggest trading partners to reduce the number of illegal immigrants and the quantities of fentanyl drugs crossing the US border.5 All in all, as Chad Bowen and Douglas Irwin (2025) argue: "Trump focuses on Tariffs, but they are rarely the best solution to the challenges that concern his administration. Instead, the Administration should use a variety of economic policies, as most of economic problems originated within the country."6

Desmond Lachman (2024) argues that the results of the economic policies of Trump's first presidency were disappointing as far as the trade and budget deficits were concerned. Far from narrowing, the trade deficit increased by around 50% from $500 billion in 2016 to $680 billion in 2020. Meanwhile, the budget deficit approximately doubled in size between 2016 and 2019 before blowing out to some 15% of GDP in 2020 as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic.7

In his second presidency, Trump is likely to see the widening of the trade deficit soon or later. It might entice him to double down on his aggressive tariffs policy. That in turn could invite aggressive retaliation by America's trading partners, friends and adversaries, and take all stakeholders further down the path to a full-scale international trade war. That would likely lead to a global recession.

Since the reduction of the US trade deficit is not feasible even in a longer term, Trump might eventually back down from his original plan. But he views international relations on a transactional basis, and he is also a man of continuity in his belief that raising import tariffs will improve the US trade balance. So there is a serious risk of an unpredictable trade environment unfolding, at least until the mid-term elections. Furthermore, Trump is also going to scrap the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework for Prosperity (IPEF), initiated by his predecessor President Joe Biden as a rules-based trade framework in the Indo-Pacific, and thus move away from even a glimpse of regional trade liberalism in managing global common concerns and values.

Beyond abandoning the TPP concluded by President Barack Obama in 2017, Trump withdrew from the Paris climate agreement, a commitment by countries across the world to address climate change and global warming, referencing the "draconian financial and economic burdens on US". The US has also exited from UNESCO and the UN Human Rights Council.

Impact on China & Other East Asian Economies

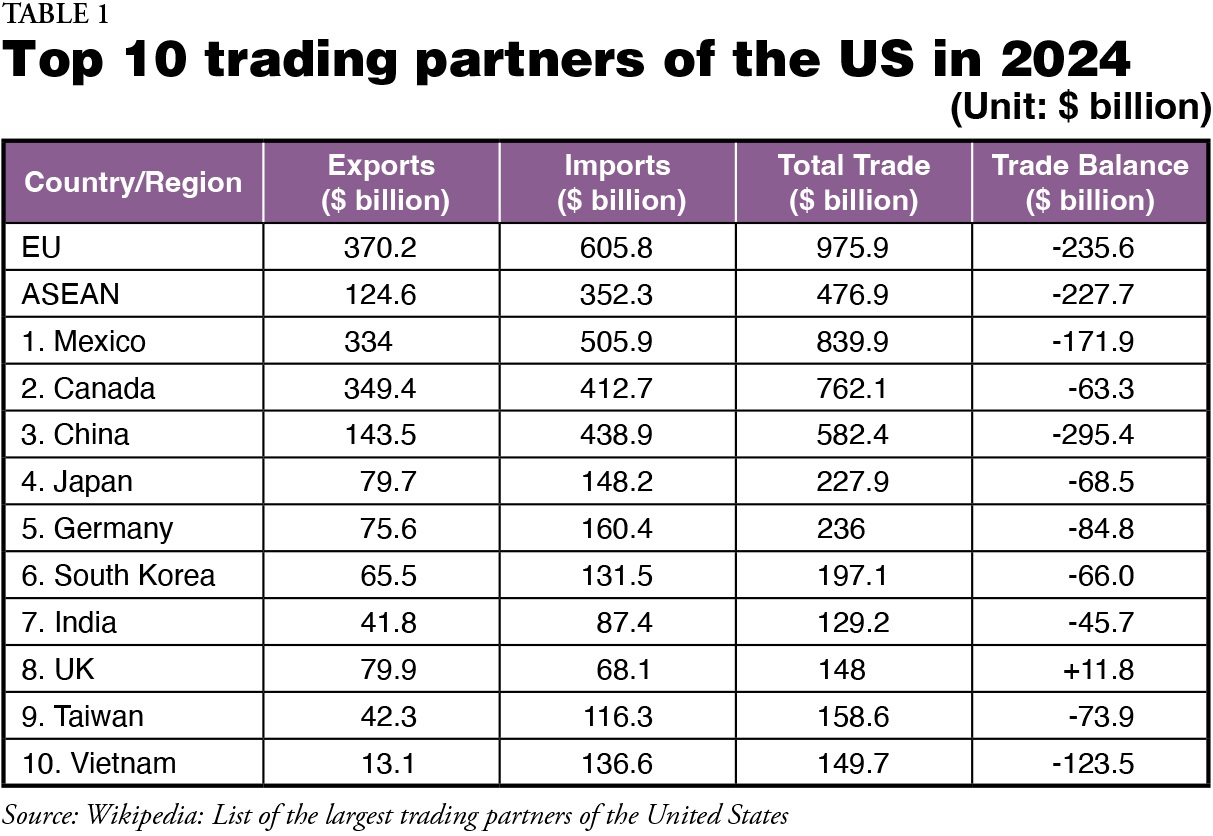

To assess the economic impacts of Trump's high tariffs policy on Asia-Pacific economies and expected fallouts from the US-China trade war, one needs to look at the how the major East Asian economies are intertwined with the US and China. As shown in Table 1, the major trade-surplus economies with the US include seven Asia-Pacific economies, Mexico and Canada from the American continent, and China, Japan, South Korea, India and Vietnam. It should be noted that all top 10 economies except Germany belong to either the CPTPP or the RCEP or both. Expanding US trading partners to the top 30 countries, important East Asian economies such as Malaysia (17) Singapore (18), Thailand (19) Australia (21), Indonesia (22), Hong Kong (25), and the Philippines (30) are included.8 Most of them have also registered a sizable trade surplus with the US. As a result, they would definitely suffer under the US high tariffs policy.

Going back further to 2021, seven Asian economies were also among the top 10 trading partners of the US to enjoy huge trade surpluses with it. The trade surplus of each of those seven economies is recorded as follows, with US billion dollars in parentheses: China (353.5), ASEAN (183.1), Japan (60.3), South Korea (29.0), Taiwan (40.2), India (33.1), and Vietnam (90.9). In terms of regional economic communities, ASEAN and the EU were the first and second largest partners of the US, respectively.

To examine the impacts of a US-China trade war, we also need to look at China's major trading partners and their trade balances. Table 2 shows that among China's top 10 trading partners in 2024 are the US, at number one, followed by South Korea, Japan, Taiwan, Vietnam, and Malaysia. So five of the top 10 trading partners are from East Asia and they will be affected by China's stagnant growth due to sluggish exports to US. Wang Tao, an economist at UBS, predicted that if 60% tariffs on China are implemented, its economic growth rate will decline by 2.5 percentage points. To the extent that East Asian economies are linked to China in trade, they will definitely suffer from such drastic decline in growth. South Korea, for example, still export 20% of its total exports to China.

Given China's economic profile in the world, the fate of East Asia's regionalism is increasingly tied to how the US and China compete and cooperate over the terms of the regional and global order. China and the US seem destined to struggle for influence and hegemony in global and regional affairs.9 In this context, one can think of three broad scenarios for how US-China relations may unfold: a) zero sum hegemonic competition with potential military confrontation, b) a status quo approach mixed with engagement and containment for competitive coexistence, c) an active compromise for multilateralism.10

In the event of a zero sum hegemonic competition even with potential military confrontation between US and China, any glimmer of hope for East Asian economic integration would suffer the devastating consequences of acute geo-economic fragmentation, if not a total global recession. However, this is not likely to happen for sheer economic reasons. Amid a tit-for-tat trade war between the big two powers, the bilateral goods and services trade linkages between the US and China still remain significant. The bilateral trade volume between the two countries reached $758.4 billion in 2022, with China's trade surplus amounting to $367 billion. The US and China need each other to trade agricultural products and daily necessities for basic consumer well-being. Without China's merchandise, Americans could not celebrate the Christmas holidays. China needs US soybeans and beef. Given the inherent interdependence between them, the second scenario of competitive coexistence mixed with the third one is more plausible.

As a result of Covid-19 and US high-tech sanctions on China, China's growth has been sluggish in recent years, growing 2.99% and 5.24% in 2022 and 2023, respectively, compared to 7.5% per annum in the early 2010s, according to Statista. On the inbound FDI front in China, it continued to grow even during the pandemic years but dropped to $163 billion in 2023 from a peak of $189 billion in 2022. Some analysts claim that China is now suffering from the middle-income trap. For sustainable growth, it would be mandatory for China to stay within a rules-based trading system and expeditiously upgrade the quality of the RCEP as the de facto anchor economy within East Asia. Reversing the declining inward FDI trend by carrying out massive deregulation is highly desirable for China.

Navigation of China & East Asian Economies to Deepen Existing Free-Trade Deals

Amid growing protectionism and subsequent trade wars between US and China, the effectuations of the CPTTP and the RCEP in sequence have provided welcome momentum for a regional rules-based trading system. East Asian economies must achieve dynamic regional growth in such a way that the US cannot ignore voices from this vital rules-based trading regionalism. Given Trump's assertive and protectionist agenda and the resulting unpredictable trade landscape, how should East Asian economies prepare themselves to mitigate expected negative impacts of Trump's trade policies?

To avoid immediate tariff "bombs" from the US, East Asia's trade surplus economies with the US need to take some timely actions to trim down one way or another their trade surplus with the US. They might include three options: a) increasing strategic imports from the US, b) reducing exports to the US, and c) making huge FDI commitments to the US following Trump's reshoring policy.

China might take one of three possible countermeasures: a) a tit-for-tat high tariff confrontation, 2) milder retaliation, and 3) muddling through with some marginal adjustments toward compromised settlements. Depending on China's reaction, smaller East Asian economies are likely to be affected by China's inevitable economic slowdown. Given the fundamental economic connectivity with both China and the US, East Asia's smaller economies want to remain connected to both of them. As a result, all East Asian economies want to see the US and China settle their differences by searching for middle ground, especially on high-tech competition.

In whichever direction the US-China trade war unfolds, East Asian economies would need to invoke the "East Asian identity" arising from the Asian financial crisis in 1997/98 to mitigate future external financial shocks by providing each other with short-term liquidity. To revive this identity, East Asian economies will need to take some concrete collective and coordinated actions in the spirit of free trade principles by making maximum use of existing regional or mini-lateral architectures to increase intra-regional trade and investment.

In fact, the East Asian economies together with some economies on the American continent have demonstrated that they are pursuing regional free trade agreements together with mini-lateral mechanisms to survive on their comparative advantages. They have already agreed on the highest standard trade and investment rules as contained in the CPTPP, effective in 2018, and to a lesser extent on the liberalization agreed in the RCEP, effective in 2022, and on a significant sub-regional economic bloc, namely the ASEAN Economic Community (AEC), effective in 2015. In a global trade landscape shifting from liberalism to rising protectionism, these three regional institutional architectures need to be strengthened and harmonized to counter the protectionist tide in the world.

Beyond those regional mega deals, middle powers in East Asia should align with each other in multifaceted and multilayered mini-lateral architectures, such as the Digital Economic Partnership Agreement (DEPA) and the Supply Chain Resilience Initiative (SCRI) to make a rules-based inclusive regional order. Often, both high-tech trade bans and "weaponization" of strategic materials under the security-trade nexus frame have been practiced by big powers at the expense of smaller and less powerful economies. The demarcation line between security sensitive high-tech products and commercial high-tech goods is increasingly blurry. Trade bans along the security-trade nexus need to be openly discussed for an agreed framework.

Against the America First policy, East Asian economies needs to respond with some collective actions in regional frameworks for internal supply chain resilience and to raise a collective bargaining position against the US. They need to take some collective actions as follows.

1) Upgrading RCEP as quickly as possible

Amid the Covid-19 pandemic and rising protectionism due to US-China competition, the January 2022 start of the RCEP is a silver lining; it is the largest free trade deal in history, covering about 30% of world GDP, 30% of the world population and 30% of world trade in 2022. For the first time, China, Japan, and South Korea (CJK) became formally interconnected under the RCEP, which also ushered in the first free trade connectivity between South Korea and Japan and between China and Japan.

Just before the outbreak of Covid-19 and while the RCEP was being negotiated, it was also fortunate that the CPTPP agreement went into effect in 2018 as the most advanced free trade deal to date in the Asia-Pacific, comprising 11 signatory states--Canada, Mexico, Peru, Chile, Japan, Australia, New Zealand, Vietnam, Malaysia, Brunei and Singapore. The United Kingdom, which joined in 2023, became the 12th state. The CPTPP is a downgraded variant of the US-led TPP, signed in October 2015 but scrapped by Trump in January 2017.

Unlike the CPTPP, the RCEP contains some important caveats. It does not include high-standard clauses on labor and the environment, an enforced mechanism to settle investor-state disputes or disciplined intellectual property rights protection, which are explicitly contained in the CPTPP. The RCEP is scheduled to eliminate about 90% of tariffs on imports between signatories within 20 years of going into force. As a result, it has been regarded as a "shallow" and slow process. RCEP parties agreed to fully liberalize only 63.4% of total tariff lines, compared to the CPTPP parties' liberalization of 86.1% of tariff lines upon going into effect. Therefore, the quality of the RCEP needs to be upgraded to the level of the CPTPP to make it significant free trade club, which the US cannot shun down the road.

Still, the RCEP's member states can benefit from unified and accumulated rules of origin and exporters' self-certification, which would be good news especially for regional SMEs. Thus, it is a great challenge for the RCEP to raise and expand the tariff concession lines and accommodate the missing chapters contained in the CPTPP.

2) Strategic convergence of RCEP to the level of CPTPP

It should be noted that there is a strong linkage between the RCEP and CPTPP. Seven CPTPP economies, namely Japan, Australia, New Zealand, Singapore, Vietnam, Malaysia and Brunei, also belong to the RCEP. It is imperative for these seven intersecting economies to upgrade the current RCEP for a strategic convergence of the two mega deals.

Despite its low level of liberalization, the RCEP agreement demonstrates that East Asian trading nations are unwilling to decouple from China and instead want to maintain ties with the region's predominant economy while ensuring that each member keeps a level playing field for trade and FDI policies. With East Asia facing US-China rivalry, Lee Hsien Loong, the former prime minister of Singapore, pointed out that "East Asian countries do not want to be forced to choose between the US and China."11

We should make the RCEP community a viable rules-based free trade bloc, even if loosely, so it can speak up against US protectionism and unilateral guardrails to ban high-tech trade in the name of economic security. The demarcation line between security sensitivity and commercial high-tech products needs to be agreed upon between the US and its trading partners. Similarly, China needs to refrain from suddenly halting exports of strategic materials while transparently implementing domestic reform.

At the same time, the CPTPP should expand its membership to include countries qualified for its advanced discipline toward a bigger and more influential platform for multilateralism. Then, the expanded CPTPP could hopefully entice the US to return to the club.

3) Acceleration of the AEC movement

ASEAN established the AEC in 2015 to promote ASEAN economic integration under a single market and production base and maintain a coherent approach toward external economic relations and increasing supply chain resilience. With its growing economic profile, ASEAN has played an important role in leveraging ASEAN centrality while dealing with external relations and managing a high-profile security dialogue mechanism, the ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF), in which major players in international security relations such as the US, Russia, China and North Korea, have been actively participating along with most East Asian economies.

ASEAN maintains a global network of alliances, dialogue partners and diplomatic missions, and numerous international affairs. It maintains good relationships on an international scale, particularly towards Asia-Pacific nations, and upholds itself as a neutral party in geopolitics. In fact, ASEAN pioneered the RCEP movement. Therefore, a highly viable AEC can be an honest broker to bring the US and China toward middle ground to prevent catastrophic consequences of their trade war. A strengthened AEC together with the ARF could help deal with protectionist trade issues under a security-trade nexus with a high diplomatic profile.

4) Strategic promotion of CJK FTA12

In order to upgrade the RCEP and ensure strategic convergence with the CPTPP, a CJK FTA in a "RCEP plus" framework is key to achieving a path toward eventual amalgamation of the two mega deals. Japan is in the driver's seat of the CPTPP and China has formally applied for membership. South Korea is weighing whether to formally apply.

In addition to the three architectures above, one should add the CJK FTA as an as-yet-unfulfilled institutional trigger to shape vital East Asian regionalism. The CJK economies are immediate neighbors, and among the top economies in the world--China, No. 2; Japan, No. 4; and South Korea, No. 14. Can East Asian regionalism be revived to reverse the waning trend of an international liberal order? To answer this question, a revival of the stalled CJK FTA negotiations that embraces a "RCEP plus" framework would be a key to mitigating the harmful impacts of geo-economic fragmentation and could even save the fragile liberal trade order in East Asia. In particular, we witnessed that a sudden halt of intermediate goods due to pandemic-induced lockdowns and some unilateral sanctions of strategic intermediate goods and materials for political reasons have seriously damaged the once-robust trilateral regional supply chain system.

The three nations have all benefited greatly from the liberal trading system, becoming global manufacturing hubs by taking advantage of naturally emerging regional value chains arising from geographical proximity and inherent structural complementarities. They accounted for 24.1% of world GDP, 19.9% of merchandise exports and 16.4% of world merchandise imports, as well as 20% of the world population in 2023. The three countries are an absolutely dominant part of the RCEP bloc.

Intra-CJK trade connectivity is clear from Table 3. The three countries were within the top four as each other's trading partners in 2023. For South Korea and Japan, China is the top trading partner. For China, Japan and South Korea are its second- and third-largest trading partners, serving a critical role in supply chain networks. The CJK trilateral FTA negotiations began in 2013 and have gone through 16 rounds without substantial progress; they have stalled since the outbreak of Covid-19 and the geopolitical tensions that followed. If the three countries can agree on a trilateral FTA with a more liberalized framework than that of the present RCEP, it could promote a strategic RCEP-CPTPP convergence.

It is significant that they are now formally but indirectly connected for the first time under the RCEP roof. One basic reason the CJK FTA negotiations were suspended is that the three countries adopted different FTA strategies. China is known for its selective and gradual approach to FTAs, preferring a moderate-level trilateral FTA and primarily focusing on trade in goods. Both South Korea and Japan prefer a comprehensive FTA in terms of scope and content, including services, investment, government procurement, IPR and technical standards.13

Once a CJK FTA in an RCEP-plus framework is reached, it will be relatively easy to upgrade the quality of the RCEP given the CJK's dominant economic position and the rest of the RCEP economies being unified under trade liberalism. A significantly upgraded RCEP via CJK's joint efforts is likely to bring it closer to the CPTPP standards. If this strategic convergence is realized, the ideal of the Asia-Pacific Free Trade Area (APFTA) envisioned by the leaders of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation forum in 2016 would be feasible, and serve as a great stepping stone for reviving WTO multilateralism.

5) Smooth cross-border FDI flows with effective aftercare service

In the past three decades, East Asian economies have deepened their natural intra-regional connectivity by liberalizing trade and FDI regimes fueled by China's rapid economic growth. On the cross-border FDI front, once China was a most preferred FDI destination of South Korean firms but in 2023 China's FDI from South Korea fell to the worst level in 30 years, recording only $1.87 billion out of South Korea's total outbound FDI of $64.4 billion.14 A similar trend is also observed in Japan's FDI to China. For supply chain resilience, cross-border FDI flows need to maintain growth momentum, while reducing excessive dependence on the US. For viable CJK supply-chain resilience, as mandated under the RCEP, the trilateral flow of strategic materials and security-sensitive high-tech products should not be "weaponized" by political motivations.

Furthermore, cross-border FDIs among East Asian economies once in place need to be well protected and equally treated like domestic firms under a South Korean-type aftercare system for multinational enterprises operating in the country.15 Providing host economies' with preemptive resolutions of grievances raised by multinational enterprises will allow mitigation of potential investor-state dispute cases. Protected intra-East Asian FDI flows are crucial for regional supply chain resilience.

With the fully implemented RCEP mechanism, it is imperative that CJK leaders live up to the spirit of trilateral common prosperity as emphasized by the joint statement at the Chengdu Trilateral Summit in 2019 and the Seoul Trilateral Summit in 2024, which resumed after a four-year suspension.

Conclusion

These three main institutions in the Asia-Pacific--the CPTPP, RCEP, and AEC--should be inclusive and open to any country sharing their underlying values. In fact, Australia, Brunei, Japan, Malaysia, New Zealand, Singapore and Vietnam belong to both the RCEP and CPTPP. As a result, the seven economies plus other trade-oriented economies can trigger a coalition of like-minded countries for an RCEP upgrade converging with the CPTPP and to strengthen the common elements of the three institutions for strategic cooperation toward a stable and prosperous Asia-Pacific.

Viewed through the lens of the increasingly bitter US-China rivalry, the future of East Asian economic integration under a rules-based order can seem bleak. But most countries in the region have benefited greatly from a liberal trade order and China, Japan and South Korea especially have ample reason to nurture and expand new trade arrangements like the RCEP and the CPTPP, and hence to work for a trilateral CJK free trade pact therefrom, with the goal of eventually reviving WTO multilateralism.

While the US pursues nationalism in isolation to regain undisputed hegemonic power status, East Asian economies should stay within a rules-based trading bloc, which the US cannot shun in the years to come. This will strengthen the bargaining position of East Asian economies collectively against US protectionist policies. Such collective action can help to maintain the legacies of the multilateral trade order. It is also hoped that even in a highly unstable world structure, Trump can still use American power, alliances, and economic statecraft to defuse and minimize conflicts, and furnish a baseline of cooperation among countries big and small.16

In a mini-lateral framework, East Asian economies also need to encourage intra-regional tourism by facilitating entry processes with some open sky agreements for an immediate economic effect in this turbulent transition period. Furthermore, a green growth model and digital trade mechanism should be encouraged among East Asian economies to create a constructive building bloc toward multilateralism to address global challenges.

While witnessing an "unraveling" of the liberal trade order, in a cautious note by P. K. Goldberg "today's escalating trade war could be viewed as a painful but temporary transition toward a revised multilateral framework that better reflects the evolving balance of power."17 For that purpose, altogether, East Asian economies should stay within functionally diverse mini-lateral and regional alignments, but not to the demise of WTO multilateralism completely.

References

1. Nick Timiraos, "Trump's tariffs aim to create a new world economic order," Wall Street Journal, April 3, 2025.

2. Phil Gramm & Donald J. Boudreaux, "Trump's Myth of the Trade Deficit: Economic growth depends on deregulation, tax cuts and the budget deficit, not on the balance of trade," Wall Street Journal, Feb. 20, 2025.

3. Paul Kiernan, "Worries Mount That Trump Agenda Is Testing Economy's Resilience: While it's too soon to tell if growth is in trouble, 'soft' survey data and markets show growing concern," Wall Street Journal, March 1, 2025.

4. Marcus Noland, "The economic implications for Asia of the Trump Program", Asia-Pacific Bulletin, Number 706, Nov. 2024.

5. Goldman David, "There is a method behind Trump's tariff madness," CNN, Feb. 10, 2025.

6. Chad P. Bowen and Douglas A. Irwin, "The Incorrect Case for Tariffs: Trump's Fixation on Economic Coercion Will Subvert His Economic Goals," Foreign Affairs, March 11, 2025.

7. Desmond Lachman, "Trump Trade Policy Follies", AEIdeas, Nov. 12, 2024.

8. The numbers in parentheses indicate the ranking of total trade with the US.

9. John G. Ikenberry, "The Future of Liberal Order in East Asia" in Peter Hayes and Chung-in Moon (Eds), The Future of East Asia, Palgrave and Macmillan, 2018.

10. Ahn Choong Yong, "Toward an East Asian Economic Community: Opportunities and Challenges" in Peter Hayes and Chung-in Moon (Eds), The Future of East Asia, Palgrave and Macmillan, 2018.

11. Lee Shien Loong, "Endangered Asian Century: America, China and the Perils of Confrontation" Foreign Affairs, July/August, 2020.

12. This subsection draws heavily from Ahn Choong Yong, "China, Japan, and South Korea can offer hope for East Asian Regionalism," Global Asia, Vol. 19, No. 3, September 2024.

13. Li Xirui, "What's Next for the Long-Awaited China-Japan-South Korea FTA" The Diplomat, Jan. 28, 2022.

14. Accessed Sept. 11, 2024, https://www.firstpost.com/world/south-koreas-investment-flow-in-china-slumps-to-worst-in-over-30-years-13749140.html

15. Ahn, Choong Yong, South Korea and Foreign Direct Investment: Policy Dynamics and the Aftercare Ombudsman, Routledge, 2023.

16. Michael Kimmage, "The World Trump Wants: American Power in the New Age of Nationalism", Foreign Affairs, March/April 2025.

17. Pinelopi Koujianou Goldberg, "Making Sense of the Tariff Chaos", Project Syndicate, March 20, 2025.

Japan SPOTLIGHT May/June 2025 Issue (Published on May 15, 2025)

(2025/05/20)

Choong Yong Ahn

Choong Yong Ahn is distinguished professor of economics at the Graduate School of International Studies, Chung-Ang University, Seoul, former chairman of the Korea Commission of Corporate Partnership, and former president of the Korea Institute of International Economic Policy. He is the author of South Korea and Foreign Direct Investment: Policy Dynamics and Aftercare Ombudsman, Routledge 2024, and co-editor of India-Korea Connections in the Indo-Pacific: Minilateralism to Multlateralism, Routledge, 2025.

Japan SPOTLIGHT

- Coffee Cultures of Japan & India

- 2025/01/27