HOME > Japan SPOTLIGHT > Article

Interview with Researcher & Cultural/Visual Anthropologist Dr. Steven Fedorowicz

Intersection Between Language & Culture: Probing Japan's Deaf/deaf Society

By Japan SPOTLIGHT

Japan SPOTLIGHT was pleased to interview Dr. Steven C. Fedorowicz, a cultural anthropologist, visual anthropologist and associate professor of anthropology in the Asian Studies Program at Kansai Gaidai University, online on Aug. 13. Dr. Fedorowicz, whose own experiences led him to see deafness as a social and legal construct, compares the deficit and cultural models of deafness, explains the various languages used by Deaf and deaf people, and explores ways in which mutual understanding with the non-deaf can be deepened.

JS: First, could you please introduce yourself, in particular your academic background and the history of your personal interest in deaf/Deaf culture in Japan?

Fedorowicz: I was born in Superior, Wisconsin, and grew up in the state of Michigan. I did my undergraduate work at Michigan State University with a degree in Social Science & International Studies and an additional major in Anthropology. I did my graduate work at Washington State University where I earned a Master's and PhD in Anthropology.

As a Master's student I was able to work for a summer in a small rural village in Bali, Indonesia. This particular village has a high percentage of deaf people, due to a mutated gene. A group of researchers, including my former professor, were trying to map the gene and examine the extraordinary position of the deaf inhabitants in the village. Simply put, deafness was not considered to be a disability and the deaf people were not marginalized or discriminated against. Their participation in village life was the same as that of the hearing people, and the deaf even had some special duties. Of course, the deaf communicated through their own sign language, known as kata kolok. But many hearing people in the village could use the sign language as well. Most of the village's inhabitants are peasant farmers and commoners. Everyone needs to cooperate. So if your neighbor happens to be deaf, you use sign language. This was my first experience with deafness and sign language. It is an example that illustrates that deafness and disability are social and legal constructs. It made me question why there has been so much prejudice and discrimination against deaf people in America and Japan.

After I entered my PhD program, I spent a year at Kansai Gaidai University in Hirakata city in Osaka Prefecture for language study. I was also able to meet people in the deaf community and study Japanese Sign Language (JSL). It was then that I decided to do my PhD research about deafness and sign language in Japan, particularly in the Kansai region. I have lived in Japan for over 25 years and am an associate professor of Anthropology in the Asian Studies Program at Kansai Gaidai University.

I would like to stress that I am not deaf, or an advocate or spokesperson for deaf people. I do not speak on their behalf. I am an anthropologist who has conducted research, fieldwork and participant-observation with various deaf communities in Japan for a long time. As an anthropologist I am concerned about any form of ethnocentrism any group faces. What I can offer is my own interpretation and cultural descriptions, based on my research. I am responsible for any possible errors or confusion that arises from my work.

"Deaf" Versus "deaf": 2 Different Cultural Models

JS: What is the difference between "deaf people" and "Deaf culture"?

Fedorowicz: There are an estimated 350,000 to 400,000 hearing-impaired people in Japan. These are people who are registered at their local governments as disabled. They receive a disability handbook that identifies the type of disability and rank of severity. This ranking in part determines the amount of social welfare assistance the individual can receive. There are various levels of hearing loss among deaf people. Some have residual hearing and can hear high-pitch sounds, while some are able to hear low-pitch sounds. And there are other physical circumstances that combine with individual situations: some people are born deaf, some are born deaf with deaf parents, some are born deaf with hearing parents, some become deafened later in life, some are hard of hearing, and some are multiple-handicapped (deaf-blind, for example). These circumstances influence identity, attitudes and communication styles.

Not all deaf people are "Deaf". What is the difference between deaf and Deaf here? Let me try to briefly explain. Deafness entails much more than hearing loss. Academics, and now Japanese Deaf people themselves, present two models of deafness: a deficit model and a cultural model. The deficit model treats deaf people as disabled, handicapped, abnormal and needing to be treated, rehabilitated and/or cured. Advocates of this model work on behalf of disabled people to provide social welfare services because the deaf are seen as unable to secure such assistance for themselves.

The cultural model of deafness treats Deaf people as a cultural group and/or linguistic minority. Nothing is necessarily lacking in these people; rather, they use a form of language that is visual rather than oral. This cultural model can be seen as a social movement originating in the United States and spreading to other countries including Japan. The capital D in Deaf serves as an empowering device that marks these people as a cultural group, similar to the capital J in Japanese people, B in Black people and LGBTQ in LGBTQ+ communities. To be culturally Deaf in Japan entails a sense of belonging in the Japanese Deaf World, using JSL as one's first language, marrying another Deaf person (and ideally living in a Deaf family situation) and struggling with discrimination and prejudice from the dominant hearing society.

Meanwhile, the use of small-d deaf refers to the hearing loss, the physical condition. So not all deaf people choose to be Deaf--this involves a conscious decision and acceptance into the Deaf community. This decision also influences the language form used by the individual, group affiliations, attitudes and beliefs. It is important to better educate people on the differences between deaf and Deaf, which may not be widely known; there are many initiatives working toward that end.

JS: We have recently seen the Special Olympics in Richmond, Virginia and the Paralympics in Paris. Do many deaf or Deaf people take part in these kinds of events?

Fedorowicz: They have their own event, Deaflympics, which dates back to 1924. The next one, in November 2025, will be held in Japan. (Note: In these events, deaf athletes compete at a top level, but cannot be guided by sounds. See www.Deaflympics.com for more information.)

JS: "Deaf culture" is truly fascinating. Do you think it makes our national culture more colorful and diversified?

Fedorowicz: I believe that Japanese culture is already very colorful and diverse. Of course, it is not as diverse as America and other countries. But 3-6% of Japan's population consist of ethnic minorities. In some geographic areas, the concentration is 10%. We can add to that the other kinds of minorities like disabled people, Deaf people, LGBTQ+, Christians and other religions. There are about 30 languages other than Japanese spoken in Japan. Plus, dialects. Plus, JSL.

Japanese Sign Language & Signed Japanese

JS: What are the unique features of JSL, and how does it compare with Signed Japanese? What do you think are the important differences between the two?

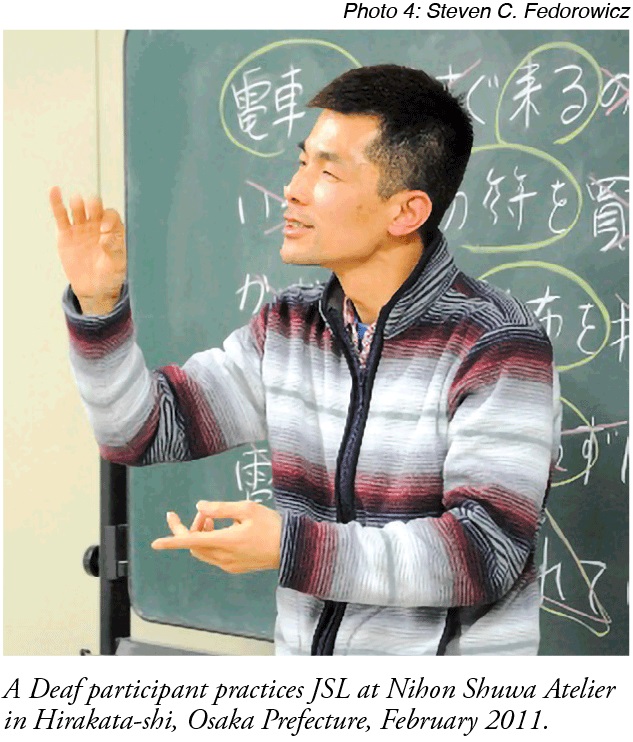

Fedorowicz: Sign languages are not universal. JSL is different from ASL, Chinese Sign Language and others. JSL is not understood by deaf communities who live outside of Japan. There is a strong connection between language and culture. Different culture means different language, whether this be spoken or signed languages. JSL is not the same as spoken or written Japanese; JSL uses a different modality. JSL has its own grammar, word order, and worldview. This involves much more than hand shape, placement and orientation, or movement. It includes all body language, especially facial expression (grammar) and imagery. JSL itself can be termed a "performance culture"--not in the sense of pantomime, but rather, grammatically speaking, as the use of "classifiers".

JSL uses a system called yubimoji (finger-spelling) for kana characters. JSL has signs based upon and representing kanji (Chinese characters). There are regional differences and dialects, such as those of Tokyo, Osaka, Hokkaido, Kyushu, etc. For example, Osaka and Kyoto are close geographically, but their sign languages are slightly different. There are also gender differences--men, women, masculine forms, feminine forms, non-binary forms, etc.--and generational differences: old, middle aged, young, children. Furthermore, there are polite forms or keigo. All of these qualities should not be a surprise linguistically, as we see the same things in spoken Japanese.

Up until now I have been speaking about JSL. But there are two major forms of sign language in Japan (with many pidgins and varieties in-between). JSL (Nihon Shuwa) is the sign language that Deaf people use amongst themselves, their mother tongue, a natural language, recently codified, analyzed and described in standard linguistic terms by Japanese Deaf linguists. In contrast, Signed Japanese (Nihon Taiou Shuwa or SJ) is the sign language used by hearing people, some deaf people, and some hearing-impaired people; it follows the same grammar and word order as spoken Japanese. Often Japanese is spoken along with the signing (while such a thing is impossible with JSL).

Signed Japanese lacks many linguistic and grammatical characteristics of JSL, including the all-important facial expressions and imagery. Hearing-people find SJ easier to study because it is basically the same as the spoken Japanese they are used to, only with some added gestures. Deaf people often find SJ confusing. For them, the meaning, the nuances, and the relationships between imagery and reality are absent in SJ. Most sign language interpreters use SJ, which can be problematic if the deaf people they are interpreting for don't fully understand it.

JS: In order to facilitate the rapid entry into Japanese society and culture by non-Japanese people, it has been suggested that "Simplified Japanese", which could be called a new language, should be created and promoted. Is there any similar movement in deaf or Deaf circles, in order to speed up communication between hearing people and the hearing-impaired?

Fedorowicz: Not really. SJ in itself is already a constructed simplified language. Most Deaf people would prefer to use JSL.

Grassroots Contributions

JS: What do you think the Japanese Federation of the Deaf and local grassroots groups have contributed to creating Deaf identity and culture in Japan?

Fedorowicz: National deaf groups work to advance the rights of deaf people and to propagate sign language. The Japanese Federation of the Deaf (JFD), founded in 1947, is the oldest deaf organization in Japan. It is highly bureaucratic and has ties with the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare. It can also be seen as inclusive, with deaf, Deaf and hard-of-hearing members.

In recent years, there have been recognition and promotion of sign language, and now there are 536 prefectures, wards, cities, and villages with local ordinances, starting with Tottori Prefecture in 2013. But this recognition is usually along the lines of the JFD philosophy that sign language is a form of communication for disabled people, similar to Braille, and not a real or separate language. Nor does the JFD acknowledge the connection between JSL and Deaf culture. No explanations of the difference between JSL and SJ, and the differences between users of each, are found in these ordinances in any significant way. This is odd because there is much research on the linguistics of JSL and other signed languages.

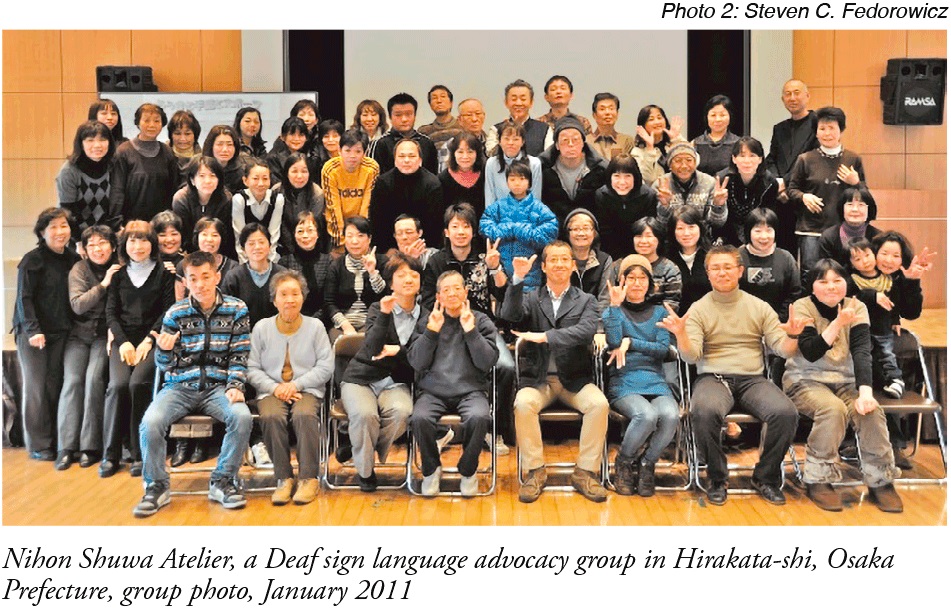

Often the most successful changes come from local grassroots initiatives, those who believe that deaf people are bicultural (Deaf and Japanese) and bilingual (JSL and reading/writing Japanese). For example, the Hirakata City Sign Language and Interpretation Training group is made up of deaf and hearing members that use JSL. After the Great East Japan Earthquake in March 2011, this group made a video on what to do in an earthquake and other disasters, providing information on shelters and other emergency services. This is very important because deaf people are among the last to get warnings and information during such disasters.

More recently this group made a video about how to use the remote sign language interpretation service on smartphones and tablets. This is very important for older deaf people without much experience with these technologies, and also for hearing people so they can become more knowledgeable about these services, how they work, and their importance for deaf people to be able to communicate. The emphasis is on common technology that all people can use, not special technology geared towards deaf people only.

Another example is a Deaf LGBTQ+ group that was founded in Osaka and Kyoto about 15 years ago. They offer lectures, workshops, support books, and video lectures about the intersections of Deaf and LGBTQ+ identities. They also teach LGBTQ+-related JSL that many might not be familiar with. These mostly young people have been very savvy with research, social media, crowdfunding and domestic and international networking.

JS: Please tell us about the various workshops promoting JSL and Deaf culture in Japan.

Fedorowicz: There are many such activities in Japan if you know where to find them. There is a wide variety of workshops, lectures and entertainment; with the common general goals of promoting JSL and Deaf culture by spreading awareness, fighting discrimination in communication and education, and creating Deaf identity in local communities. These workshops, lectures and entertainment are usually in JSL without interpretation; sometimes this is a case of singing to the choir. The challenge is to attract and educate (hearing) people without experience or knowledge of deaf and disability issues.

JS: How do you compare Deaf culture in Japan with that of other nations?

Fedorowicz: It is still growing, though is not yet as big as that in America and European countries. We are seeing more and more international relationships between deaf groups from different countries. There are about 70 countries with national sign language recognition, some as a constitutional right, some as a part of disability recognition.

Acceptance of Diversity

JS: Does the creation of Deaf culture lead to more social acceptance of diversified cultural groups, such as the cultures of immigrants speaking their own language?

Fedorowicz: We talked about diversity in a previous question. So here I would like to focus on social acceptance. This is still problematic for many minority groups because of a lack of experience or knowledge.

In 2016, the Law to Eliminate Discrimination against People with Disabilities was enacted. This is huge as it is the only national law that bans discrimination against anyone. Previously, there were no national laws to ban discrimination against women, minorities, foreigners, LGBTQ+ people, or anyone else. The goal of this law is to make life easier to some extent for the nation's 7.8 million people with impairments. It also bans "unjust discrimination" and asks government agencies and private businesses to take "reasonable accommodations" to remove social barriers. But there are shortcomings and limitations. Few people know about it or understand the issues; private-sector entities are asked to "strive" to take action in various ways, but there are no real penalties other than small fines. We need more knowledge acceptance, and generosity.

JS: What do you see as the challenges for Japan to create and promote Deaf culture?

Fedorowicz: There is no need to create it, it already exists. The problems, as we have been discussing, have to do with knowledge, acknowledgement, and acceptance. Challenges include allowing Deaf people to be a bigger part of the national discourse and policy-making, asking them what they need and want, and not making decisions of their behalf. One example is the recent trend in Japan to show television programs or plays that feature one or more deaf/Deaf person(s). This sounds a good idea in terms of increasing awareness. However, generally the actor(s) playing these roles are not themselves deaf. Some in the deaf/Deaf community feel strongly that, instead, deaf actors should be chosen to portray "themselves".

There are a lot of good ideas in areas such as Accessibility, Shifting the Mindset, Inclusive Approach, Integration not Separation, Support at the Workplace, Businesses, Education, and Media. But, as a society, we need to move from good intentions to action and implementation.

JS: Could you tell us your future plans as an anthropologist to further study this issue?

Fedorowicz: I really have not been able to do active fieldwork since the Covid-19 pandemic, because I could not leave my house to do it. But I have years of data to work with. The pandemic gave me a chance to work with my data to write papers, publish articles, and give presentations. I think this will continue.

I believe there is a strong nexus between research and teaching. I teach the Sociolinguistics of Deaf Communities in Japan course at Kansai Gaidai University. I stay in touch with deaf friends and researchers to keep up to date for the class and for my students. Every semester I have a Deaf sign language activist and teacher give a guest lecture in JSL. I interpret the JSL into English for my students. I teach a little JSL to my students and most of them enjoy it.

The question remains, how can people better understand deaf people, moving beyond surface-level and stereotypes, unless they have real involvement, real interaction, or real experience? Perhaps it is time to move beyond academic theories and models.

I am a simple ethnographer. I strive to do research and provide cultural descriptions of deaf people in Japan. I realize that my research and reporting have the major theme of Real Life. I have known some deaf people for over 25 years. I have watched some grow up, get married and have children. I have seen some get older and have grandchildren. I have seen their successes and joys. And I have seen them get sick and deal with other real-life problems. I have also seen an increase in Deaf researchers and linguists, some of whom employ English. They are writing about their own language and culture. I think we need to pay more attention to them and their incredible work.

Note: For an article by Dr. Fedorowicz on this subject, see: https://www.anthropology-news.org/articles/performance-sign-language-and-deaf-identity-in-japan/

For further reading, see: https://visualanthropologyofjapan.blogspot.com/2024/06/announcementa-primer-on-deaf.html

Dr. Fedorowicz also has a keen interest in ethnographic photography. He is a talented visual anthropologist, and has made many important contributions to the field of Visual Anthropology of Japan. His photographs and essays can be found at http://visualanthropologyofjapan.blogspot.com/

Japan SPOTLIGHT November/December 2024 Issue (Published on November 13, 2024)

(2024/12/16)

Japan SPOTLIGHT

Written with the cooperation of Jillian Yorke, who is a translator, writer and editor who lived in Japan for many years and is now based in New Zealand.

Japan SPOTLIGHT

- Coffee Cultures of Japan & India

- 2025/01/27