HOME > Japan SPOTLIGHT > Article

Brexit: Causes & Consequences

By Matthew J. Goodwin

On June 23, 2016, the United Kingdom voted by 52% to 48% to leave the European Union (EU). The vote for "Brexit" sent shockwaves around the world, rocking financial markets and rekindling global debates about the appeal of national populism, as well as the long-term viability of the EU. Aside from challenging liberalism and global markets, the vote for Brexit also highlighted deepening divides that cut across traditional party lines in British politics. On one level, the vote for Brexit served as a powerful reminder of the sheer force of Britain's entrenched Eurosceptic tradition and of the acrimonious splits among the country's political elite over Britain's relationship with Europe. But on a deeper level, Brexit should also be seen as a symptom of longer-term social changes that have quietly been reshaping public opinion, political behavior, and party competition in the UK as well as in other Western democracies.

In this essay I will set out some of the key causes of the Brexit vote, paying particular attention to the role of long-term social changes, asking: what underlying changes in British society made this historic vote possible? In the final part of the essay I shall turn to consider the consequences of this vote, exploring what the 2016 referendum tells us more generally about British and also European politics.

Why Brexit Was a Long Time Coming

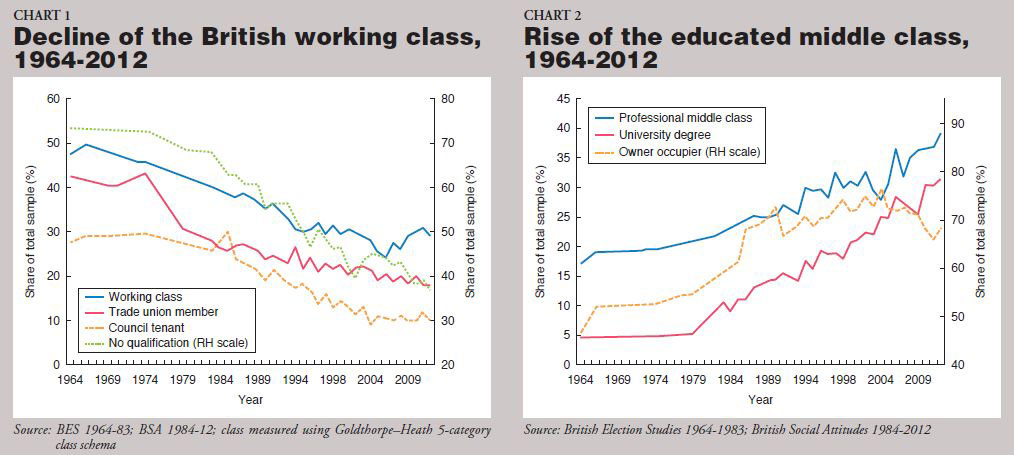

The social changes that set the stage for the UK's historic vote to leave the EU began decades ago. As we argued in our book Revolt on the Right (Robert Ford and Matthew Goodwin, Revolt on the Right: Explaining Support for the Radical Right in Britain, Routledge, 2014), one key "bottom-up" driver was a slow but relentless shift in the structure of Britain's electorate, including the numerical decline of the working class and the growing dominance of the middle classes and socially liberal university graduates (Chart 1 & 2). In the 1960s, more than half of those with jobs in Britain did manual work, and less than 10% of the electorate had a university degree. But by the 2000s, the working class had dwindled to around a fifth of the employed electorate, while more than one third of voters were graduates. These changes gradually altered the electoral calculus for the two main parties, Labour and Conservative, whose traditional dividing line had been social class.

In earlier years, when the working classes had been dominant, Labour could win power by mobilizing its core working-class support, while the Conservatives had to cultivate cross-class appeal. By the 1990s, however, the shift in the country's class structure had reversed this calculus. Labour was compelled by repeated electoral defeats and a shrinking working-class core vote to develop a new cross-class appeal, a strategy that was explicitly acknowledged and pursued by Tony Blair, who went on to enjoy a record three successive election victories. Traditional working-class values and ideology were downplayed in Blair's rebranded "New Labour", which focused instead on building a managerial, centrist image designed to appeal to the middle classes. Between 1997 and 2010, New Labour sought to attract the middle class and university-educated professionals, whose numbers were growing rapidly and whose social values on issues such as race, gender, and sexuality were a natural fit with liberalism. This proved highly successful in the short run, keeping Labour in power for 13 years.

But this success came at a price. During the same period, socially conservative, working-class white voters with few educational qualifications gradually lost faith in Labour as a party that represented them. The result was lower turnout, falling identification with Labour, and growing disaffection with the political system more generally.

From 2010 onwards, this disillusionment among the white working class, particularly over the issue of immigration, could have provided an opening for the Conservative Party. But its new leader, David Cameron, focused instead on trying to "modernize" his party, regaining support from the graduates and middle-class professionals who had drifted away from the Conservatives during the era of Blair. As a result, white working-class voters were neglected by both parties, in a country where, despite recent and rapid demographic changes, the electorate remains overwhelmingly white. In the most recent census in 2011, for example, still 87% of the British population identity as white. These white working-class voters noticed the change in their parties' behavior and reacted accordingly. They became negative about the two main parties and the perceived lack of responsiveness to their concerns. Many turned their backs on politics altogether. Apathy among the working classes increased. Eventually, in 2016, many of these voters would go on to vote for Brexit.

A second long-running social change overlapped with these demographic shifts and magnified their importance - growing value divides over national identity, diversity and multiculturalism, and liberalism more generally. The newly ascendant groups in Britain, including ethnic minorities, graduates, and middle-class professionals, held values that were very different from the more conservative and even authoritarian outlook that was held by many older, white and working-class voters, as well as those who had left the educational system early in life. As the UK's two main parties reoriented themselves to focus on the rising liberal groups, a new "liberal consensus" emerged. This was a more socially liberal outlook on the world, which saw rising ethnic diversity as a core strength, actively supported religious, racial and sexual minorities, saw national identity as a matter of civic attachment rather than ethnic ancestry and thought that individual freedoms mattered more than communal values. The increased prominence of this outlook was not just a matter of electoral expediency. It reflects the typical worldview of the university-educated professionals whose weight in the electorate is rapidly increasing, and who also came to dominate politics and media. But such values contrasted sharply with the more nationalistic and communitarian outlook of those white, working-class and economically marginalized voters, whom we term "the left behind". These voters feel cut adrift by the convergence of the main parties on a liberal, multicultural consensus, a worldview that is alien to them. Among these voters, national identity is linked to ancestry and birthplace, not just institutions and civic attachments, and a much greater value is placed upon order, stability and tradition. The policy preferences of the left behind reflect this. Unlike those who would later go on to vote to remain in the EU, the white working class not only favored harsh responses to criminals and terrorists who were seen as threatening social order but also much tougher restrictions on immigration. Thus, the very things that liberals celebrate - ethnic diversity, the shift to transnational identities and rapid change - strike the left behind as profoundly threatening.

Mobilizing the Left Behind

As the UK approached the 2016 referendum, many of its mainstream politicians were not only ignoring the values and priorities of the left behind, but promoting a vision of Britain that the left behind found threatening and rejected. Long before the vote there was a growing pool of electorally marginalized, politically disaffected, and low-skilled white working-class voters whose values were increasingly at odds with the liberal consensus.

The left behind were available to form the nucleus of a new movement but they needed an issue and a party to crystallize their inchoate discontent and to mobilize it into politics. The issue would arrive in the mid-2000s in the form of unprecedented levels of immigration into the country, and this would be followed by the arrival of a new political party - the UK Independence Party or UKIP - that campaigned to reduce this immigration and also leave the EU. Between 2010 and 2016, UKIP became the primary vehicle for public opposition to EU membership, mass immigration, ethnic change, and the socially liberal and cosmopolitan values that had come to dominate the establishment.

The spark that lit this populist revolt was a fateful decision by Blair in 2003. Unlike most other EU member states, Britain opted not to impose temporary restrictions on the inward migration of EU nationals from the so-called A8 states in Central and Eastern Europe that were due to join the EU in 2004 - the Czech Republic, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Hungary, Poland, Slovakia, and Slovenia. Britain's low unemployment and generally strong economy attracted EU migrants in much larger numbers than originally forecasted by the government. Net migration to Britain had already been rising before the decision, but the influx from Central Europe boosted the numbers and made controlling them more difficult. Net migration rose from 48,000 to 268,000 per annum between 1997 and 2004 and continued to rise, topping 300,000 in the years immediately before the referendum.

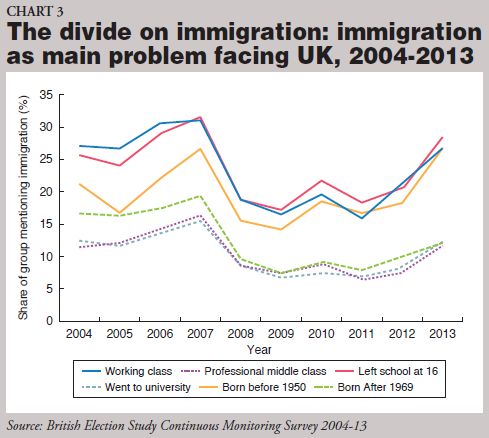

This influx produced a strong reaction among voters, who became very concerned about rising immigration. The share of voters naming immigration as one of the nation's most important issues increased from under 3% at the start of 1997 to around 30% in 2003 and then to over 40% toward the end of 2007 - a record high. After that point, immigration was routinely named by voters as one of the top two most important issues, even in the depths of the financial crisis and the recession. By the time of the EU referendum, immigration had been at the top of the political agenda for well over a decade, something which had never happened before in British politics (Chart 3).

The majority of voters in favor of reduced immigration realized that the EU was a key obstacle to achieving that goal, and consequently became more skeptical about the UK's continued EU membership. Anxieties about the perceived effects of migration on public services, welfare, and identity were further cultivated by a strident and populist tabloid press, which routinely opposed immigration. Front-page stories blaming EU migrants for social ills, and demanding action to control their numbers, became a regular occurrence after 2004.

Though both Labour and the Conservatives were keenly aware of the growing disquiet, neither could find an effective response given the external constraints on policy at the EU level. In an era of free movement, where EU nationals were free to work and settle in other EU member states, tight immigration controls were simply impossible. Labour defended immigration as economically and socially beneficial while the Conservative Party committed a major error by promising voters that it would reduce net migration "from the hundreds of thousands to the tens of thousands". This was an ill-advised promise, as EU treaty rights guarantee the free movement of EU nationals, making such a degree of control impossible so long as the UK remained in the EU. Thus, the target was never met and further angered voters who favored sharp reductions in immigration. Voters anxious about immigration lost faith in the ability of the main parties to manage the issue.

Rise of a New Challenger

Immigration was the political catalyst for these voters, symbolizing the value divides that had put them at odds with the mainstream liberal consensus, eroding their trust in the traditional parties and the political system, and providing an opening for a new challenger. By 2015 UKIP had become the most successful new party in English politics for a generation (see Matthew Goodwin and Caitlin Milazzo, UKIP: Inside the Campaign to Redraw the Map of British Politics, OUP, 2015). By fusing its original message of withdrawal from the EU with opposition to immigration, UKIP was able to catch the angry public mood, and its leader Nigel Farage quickly attracted rising support. UKIP finished in first place in the 2014 European Parliament elections, becoming the first party other than Labour or the Conservatives to win a nationwide contest since 1906, and then went on to win almost 4 million votes at the 2015 election, or nearly 13% of the national vote.

The rise of UKIP was fueled mainly by disillusioned former Conservative voters and so was a key factor that led Cameron to commit to holding a referendum on the UK's continued EU membership in 2013. Three years later, and after Cameron and his party had won a surprise majority government, thus committing Britain to a referendum, the prime minister completed an intensive round of negotiations over the terms of EU membership. He did obtain a few concessions. These included an opt-out from the declaration in EU treaties committing member states to an "ever closer union among the peoples of Europe", as well as an "emergency brake" whereby a member state could apply to the European Commission for permission to suspend benefit payments to EU migrants if they were placing too great a burden on social services. But these were not major reforms and failed to satisfy the white, working-class and left behind voters who would go on to vote for Brexit mainly because of their concerns over immigration (Harold D. Clarke, Matthew Goodwin, and Paul Whiteley, Brexit: Why Britain Voted to Leave the European Union, CUP, 2016).

During the 2016 referendum campaign, however, the pro-EU "Remain" side downplayed these identity-related concerns. Instead, the Remain campaign focused almost entirely on appeals to people's fears about risks to the national economy, their own finances and to self-interest. This relentless appeal to economic interest was reflected in claims by the Treasury that each household would be £4,300 worse off annually if the country voted for Brexit. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) only days before the vote warned that leaving the EU would harm British living standards, stoke inflation, and by 2019 reduce economic output by 5.5%. A further warning from Chancellor of the Exchequer George Osborne said that such an outcome would necessitate harsh public spending cuts and tax increases. Businesses also intervened. One letter from 198 business leaders warned that Brexit would threaten jobs and put the economy at risk.

But what the Remain camp had failed to grasp was that ahead of the vote most voters accepted that leaving the EU would be economically costly, both to the economy and their own finances. Yet they were prioritizing their immigration concerns. This meant that the pro-Brexit "Leave" campaigns, which focused heavily on immigration, were far more emotionally resonant and in tune with the core concerns of voters. Vote Leave claimed that EU membership cost Britain £350 million per week ("Enough to build a brand new, fully-staffed NHS hospital every week"); that more than half of net migration came from the EU; and that voters should reject the possible future flows of migration that could come from states such as Albania, Macedonia, Serbia, and Turkey.

Brexit Delivered

In the end, these currents bubbled to the surface on the day of the vote. The Leave win with 51.9% of the vote was larger than any of the late polling had expected. The lead for Leave was even stronger in England, where 53.4% voted for Brexit. Local authorities across the length and breadth of England, from rusting postindustrial Labour heartlands to prosperous Conservative suburbs, reported big majorities for Leave on very high turnouts - the overall turnout was the highest recorded in a UK-wide vote since 1992.

Local jurisdictions with large numbers of pensioners and a history of voting for UKIP recorded very high turnouts and Leave shares. This was particularly so in parts of eastern England with large numbers of left behind voters. Brexit also attracted majority support in approximately 70% of Labour-held seats, winning especially strong backing in poorer northern postindustrial areas. At the other end of the spectrum stood London, Northern Ireland, Scotland, and the university towns, such as Oxford and Cambridge. Of the 50 local jurisdictions where the vote to remain in the EU was strongest, only 11 were not in London or Scotland, and most were areas with large universities. In a country that was now divided on unfamiliar lines, London - home to the political, business, and media elite - was profoundly at odds with the country that it had come to dominate and overshadow. London wholeheartedly embraced Europe, even as most of England emphatically rejected it.

Conclusions & Consequences

So what are the consequences of the Brexit vote? As the dust begins to settle, all the parties are struggling to come to terms with a political landscape that was profoundly changed by the events of June 23 and with an agenda set to be dominated for years by the most complex and high-stakes international negotiation in modern British history. Whatever approach the government pursues in implementing the referendum verdict, Brexit has accelerated the polarization of values, outlooks, and priorities that increasingly divides university-educated cosmopolitans from poorly qualified nationalists.

The coming period of difficult and protracted negotiations between the UK and the EU will most likely entrench the divides separating England's socially liberal youth from socially conservative pensioners, and its diverse and outward-looking cities from its homogeneous and introspective small towns and declining industrial heartlands. If anything, these divides were only entrenched by the outcome of the 2017 general election which saw the electorate become even more polarized along the lines of age.

The 2016 vote laid bare the depths of the divisions between these groups and placed them on opposite sides of the defining decision for a generation. Both of the main parties now have to wrestle with internal conflicts between Leavers and Remainers, between those who want to prioritize single-market access and those who want to prioritize stronger curbs on free movement and migration. Demands for a clear voice for Remainers are likely to grow as the problems and uncertainties of Brexit accumulate, and if neither traditional party is able to provide them with one, then at some point they may seek it elsewhere. Leave voters also pose problems for the parties. Their clear preference for immigration controls on EU workers is considered by many in Europe to be incompatible with Britain's retaining full access to the single market. This puts Prime Minister Theresa May in the difficult position of trying to negotiate a new agreement with the EU that maximizes access to European markets for the City of London, while including the more radical immigration reform that Leave voters clearly want. May's challenge is magnified by the fact that few comprehensive trade agreements have ever been resolved in a short timeframe, and the Brexit negotiation is likely to be more complex than most. A transitional deal may ease pressures, but it would be unlikely (at least initially) to deliver the immigration restrictions that Leave voters expect to see.

On the other hand, if the government prioritizes swift action on immigration control over access to European markets, this could have large and unpredictable consequences for the economy. It is possible that any viable deal will produce a significant backlash, regardless of its contents. Many Leave voters have very low trust in the political system, yet high expectations that Brexit will reverse the entrenched social and economic changes they oppose. Such expectations may be impossible to meet. A reckoning would then be inevitable, and would open a new window of opportunity for radical right-wing populists. Managing the inevitable disappointment and disruption that will follow Brexit will be the government's biggest challenge, while stoking and mobilizing a popular backlash may be UKIP's best opportunity for post-Brexit renewal.

The origins of the vote for Brexit, then, can be traced back over decades to changes in British society and politics that, by the 2016 referendum, had left a growing segment of older, white, nationalist, and socially conservative voters feeling marginalized from mainstream politics and opposed to the socially liberal values that have become dominant in their country. The 2016 referendum and the vote for Brexit exposed and deepened a newer set of cleavages that are largely cultural rather than economic. Across the West the divides between nationalists and cosmopolitans, or liberals and conservatives, cut across old divisions and present established parties with new and difficult challenges. In the UK, negotiating an exit deal with the EU is the primary policy challenge for the government today. But for all the country's parties, articulating and responding to the divisions laid bare in the Brexit vote will be the primary challenge of tomorrow.

Japan SPOTLIGHT November/December 2017

(2017/11/24)

Matthew J. Goodwin

Matthew Goodwin (Ph.D., University of Bath) is professor of politics at Rutherford College, University of Kent, and visiting senior fellow at the Royal Institute of International Affairs, Chatham House. He is known for his work on Britain and Europe, radicalism, immigration and Euroscepticism. He contributes regularly to debates and discussions on such media as BBC News, Bloomberg, Sky News, Al Jazeera, Radio 4, and CNN. He tweets @GoodwinMJ

Japan SPOTLIGHT

- Coffee Cultures of Japan & India

- 2025/01/27