HOME > Japan SPOTLIGHT > Article

North Korea: Myths & Reality

By James E. Hoare

Introduction: North Korean Experts Are Rare Birds!

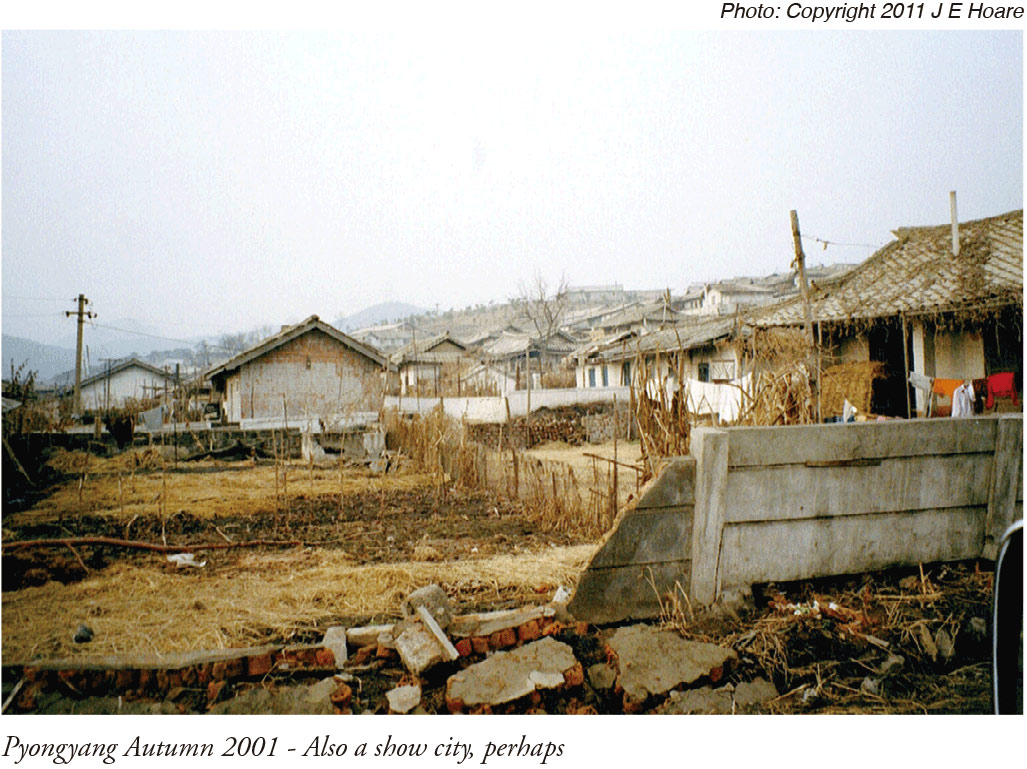

First a word of caution. Kim Jong Il, the leader of North Korea from 1994 to 2011, told a group of visiting journalists from South Korea in 2000 that anybody who presented themselves as an expert on his country was a fool. Having studied the North since the mid-1970s, visited several times, and lived there for 18 months in 2001-2, I am inclined to agree. Just when it seems obvious how things work in the country, a new twist throws you off balance and the certainties of yesterday are swept aside. It is not just me. The number of predictions about the future policy or the chances of survival of the country that have been proved wrong is legion. North Korea is adept at allowing visitors to see only what it wants them to see. It is not impossible to get around this. To do so, however, you must keep your eyes and ears open. Do not take things at face value. Probe as much as you can but do not be rude and do not break the rules. What would cause no problems in most countries may not be treated with much tolerance in North Korea as some have found to their cost.

Demonizing Is Easy

Demonizing North Korea is easy. For many commentators, it is the default mode. They do not analyze the country nor try to understand it. They know that it is evil, or that its policies are wrong. The most famous exponents of this view were probably US President George W. Bush and his senior colleagues, who famously did not negotiate with evil, but, they said, destroyed it. Unfortunately for them, the need to deal with the reality of the North Korean nuclear program proved stronger than the unwillingness to negotiate. But Bush and his men were by no means alone. North Korea arouses strong emotions. The strength of those emotions can spill over into vitriolic exchanges on social media, in conventional media and even in academia. Nuance disappears, black and white prevails.

The process begins early. Few use the country's official title – the Democratic People's Republic of Korea – or even the abbreviation DPRK. Some avoid the official usage because they do not want to give legitimacy to a state that, in their view, has no right to exist. To them, there should be no division on the Korean Peninsula. Korea was one for over 1,000 years. It should not be divided. Even the Japanese colonial administration did not do that. For many people with little knowledge of history, it is the North that is blamed for the division. But the process that saw the emergence of two separate states on the peninsula started long before the Korean War. Outside powers – the United States and the Soviet Union – carried out the initial division. Their intentions were initially limited to taking the Japanese surrender. The Cold War intervened, and the two powers oversaw the development of separate states on the peninsula. The leaders of both states wanted unification. Each denied the other's right to existence. (To some degree, they still do, summit meetings notwithstanding.) Belligerent noises and threats came from both. The North struck first. Although the smaller in population, it had the means to do so thanks to the Soviet decision to give it an army. The US made a different decision. South Korea had a lightly armed super police force that proved no match for the forces from the North. If there had been no outside intervention, the problem of Korean unification would have been solved in 1950. But intervention there was, and the war settled nothing. Now two even more hostile states faced each other across the division line, initial hostility made worse by the bitterness of war.

Relations between the two Koreas were not helped by the rest of the world. During the war, the United Nations had set up a commission – the UN Commission for the Unification and Rehabilitation of Korea (UNCURK) – that pledged to bring about the "rehabilitation and reunification of Korea" which followed on from its 1948 declaration that the South was the "only legitimate government on the Korean peninsula". Although the wording did not say that it was the only government on the peninsula, it acted as though that was what was meant, a position that Western countries went along with. Not until the early 1970s, with the first substantive contacts between the two Koreas since the Korean War and the winding-up of UNCURK, did the position change and Western countries begin to open diplomatic links with the North.

From the war onwards, the default mode outside the North for referring to the two Koreas was "Korea" for the South and "North Korea" for the North. The implication, clearly, was that the South was the real Korea. (Something similar happened in the case of divided Germany and Vietnam.) The North was odd, an aberration. Of course, there were ways in which the North contributed to this image. It was a tough totalitarian regime that maintained a fierce independence. Few visited it. Even among the socialist states, it was seen as a difficult partner; it was grasping and needy and it went its own way as far as it could.

The Odd Place

The North was seen as a threat but also as a strange, bizarre place. Both themes persist. Exaggerated claims about its military might abound. Its rhetoric is indeed ferocious. Yet it is in reality cautious, behaving like many small states surrounded by much bigger states, all far better equipped. When not dealing with its alleged threat to world peace, most press reports on the North are dominated by what is seen as its weird nature. In recent years, these themes have included the claim that the North believes in unicorns, or focused on the strangeness of the leader's hairstyle, while in July 2016 the British newspaper, the Daily Mail, reported that Kim Jong Un was devastated by international sanctions on luxury goods because of his love of Swiss cheese and watches. We have had giant rabbits, catfish and a regular diet of weird leaders doing odd things – all are jumbled together whether true or not. To many it is the worst country in the world in a host of areas from human rights (yet look at some African or Middle Eastern countries) to architecture (most former Soviet cities could compete on that score).

But It Will Not Just Fade Away

A persistent theme is that the North is doomed to collapse any day now. Even the failure of this to happen so far does not stop the predictions. As with those who believe the end of the world is near, if it does not happen at the predicted time, it will certainly do so next time – or the time after that. In 1949, the British Cabinet noted a report from the Seoul Legation that the North Korean army was disaffected, there was widespread starvation in the country, and that the regime was on the point of collapse. Forty years later, the British commentator Aidan Foster-Carter wrote, following the collapse of the Soviet Union, that North Korea would be next, if not in two years, certainly in five. When that did not happen, he twice more gave it five years, then stopped predicting.

The fact is that the North has survived despite war, invasion, the longest sanctions regime in the world, economic collapse and the end of its main trading partners, famines, floods and drought. Soviet forces had liberated the north of the peninsula in 1945. The Soviet Union may have enabled the Communist forces to dominate the area and undoubtedly played a major role in the establishment of North Korea. Dependence on Soviet guns to maintain its position was ended by 1949. It was China that saved it during the Korean War, not the Soviet Union. Unlike the states of Eastern Europe, from the 1950s onwards it moved to a more independent position, drawing as much on Korea's historic past and even on the practices of the Japanese colonial administration to give the state legitimacy. The collapse of the Soviet Union, which caused the collapse of Communism in Eastern Europe, worried the North, but it did not have the same effect on it as it did on the European states.

Unification?

The complication for North Korea is in some ways similar to that faced by the German Democratic Republic (East Germany) in 1989-90. Once the Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev made it clear that the Soviet Union would no longer support their Communist leadership, states such as Hungary or Poland could change government without fear of challenge. East Germany, however, had until 1945 been part of a unified Germany. Its people had been exposed to the German Federal Republic (West Germany) through radio, television and direct contact. Many wanted a return to a united Germany. There was some opposition from other countries that had fought Germany in World War II and feared a united Germany would be too powerful. This was overcome, and the two German states merged into one. But an East-West divide persists. Although they had not fought each other, as the Koreas had, divisions had grown up between them that proved hard to overcome. East Germany had a smaller population than the West. Its economy, although widely regarded as the strongest in the former Soviet sphere of influence, lagged well behind. Its industries were old fashioned compared to the West. In some areas, it is true, it was ahead. Social security and health provisions were more evenly distributed in the East, based on need rather than the ability to pay. There was one other problem in the relationship. Suspicions of the East in the now dominant West led to many job losses amongst those who had worked for the East German regime. Some were tried and sentenced for having carried out state policies.

All this resonates with North Korea. The elite are aware of what happened in East Germany, in Libya and Iraq. Some of that group are well aware of the voices in South Korea that call, not for reconciliation, but for revenge. At best the senior leadership sees loss of status and loss of jobs. At worst they see the prospect of being executed or imprisoned. It is preventing this outcome that keeps them loyal to the system and its leader, not the bottles of brandy or even the fast cars that Kim supposedly gives out from time to time. To quote an old proverb, they hang together – stay united – or they hang separately.

Even if the worst did not happen, the North Korea leaders have had clear indications over the years that there is a quasi-colonial attitude towards their country in the South. This was made abundantly clear during the Lee Myung-bak and Park Geun-hye presidencies. In South Korea, companies and the government see the North, if not quite virgin territory, as ready for exploitation. The South will help with developing existing resources and looks forward to exploiting a literate and obedient workforce. This does not bode well. Many will know how hard it is for those from the North who have gone to the South to fit in, whether they are from the non-political classes or from the elite.

In the South too, there are doubts about the idea of reunification. Back in 1989, the South witnessed a brief surge of enthusiasm for the idea, as Eastern Europe was transformed. It was not long, however, before doubts began to creep in. Having only just begun to reap the benefits of the economic development since the early 1970s, many looked askew at giving them up to pay for sorting out the North. The famine years of the 1990s made things worse. It became clear that the North was no paradise. Most of its much-vaunted achievements were well in the past, indeed if they had ever existed outside the pages of glossy magazines. Costs of reunification in Germany proved far greater than anybody had expected.

Dealing with Reality Not Dreams

Unification thus seems unlikely in the foreseeable future. Perhaps one day, when all those who experienced the Korean War years have passed on, and when the two sides get to know each other better, it may happen. But there is a long way to go. So, there is little choice but to deal with the North as it is, not as one might hope that it might be.

Here it would help if one got away from the overheated discussions on the threat from the North. Nobody would deny that the North has been an irritant to its neighbors, but beyond the South it is not a threat to their existence. Even in the case of South Korea, 2019 is not 1949. The balance of power has shifted in most matters to the South. Even the possession of nuclear weapons does not give a real advantage. The use of such weapons on the peninsula would not only lead to massive retaliation but could have an effect on the North itself.

A real threat to the US or, even more unlikely, to Europe, seems far-fetched. Former US Secretary of Defense William Perry pointed out the huge discrepancy between the North and the US. If the former were to use any of its tiny nuclear arsenal against the US, it would face a counterattack that would certainly mean the end of the regime and possibly the complete destruction of the country. This would be President Donald Trump's fire and fury with a vengeance. And while the North has shown that it will practice brinkmanship, it has not shown itself suicidal.

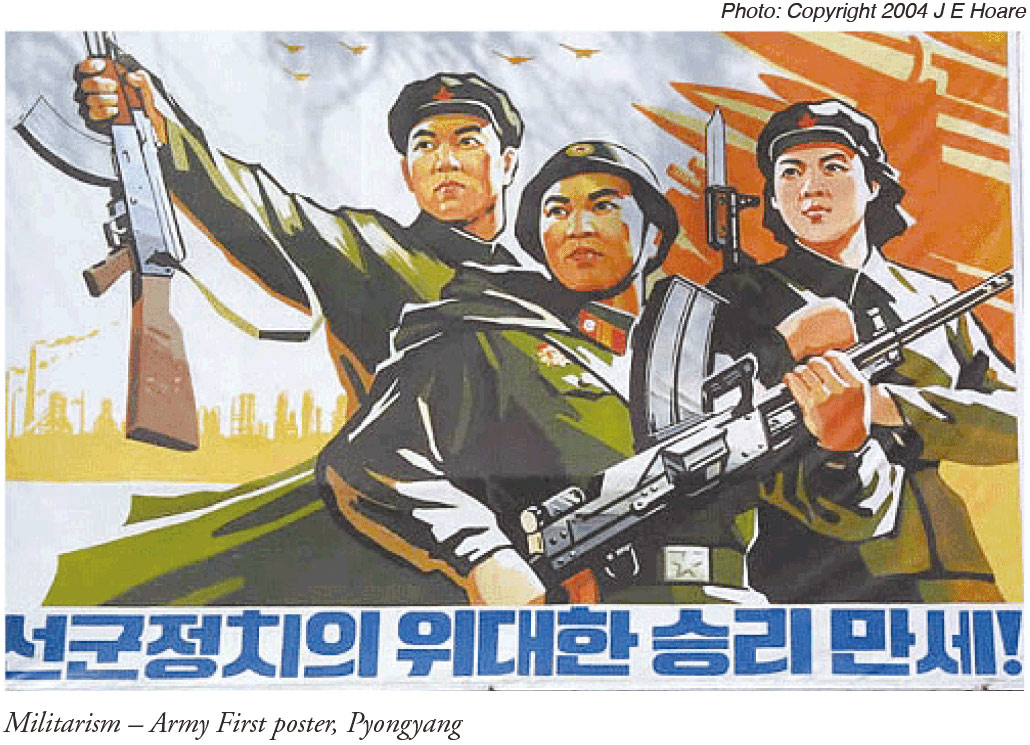

Yes, Kim Jong Un has made threats and shown warlike scenes. The armistice agreement has been denounced and declarations of war are regularly flung about. But nothing happens. The North still respects the armistice. There have been so many assertions that this or that development is an act of war that it is hard to take them seriously. Kim in the control room would look more authentic if the computers were plugged in and the telephones were connected. Or even if the map on the wall did not look suspiciously like a blown-up airline route map rather than the rocket trajectories against the US that it claimed to be. What is forgotten is that such pictures are primarily for internal consumption, designed to show a leader in control and standing up to the enemies of the North.

You Cannot Trust Them!

That North Korea does not stick to its treaties and agreements is by now a well-established mantra. It is certainly a tough negotiator. Like other East Asian countries, it is usually more attached to the general spirit of a document than to the precise text. If, however, it is to its advantage to be more precise, it will be. What its negotiators do expect is that there will be equal and mutual advantage. If there is backtracking or a lack of reciprocity, to the North that excuses it from meeting its side of the bargain. Essentially that is what happened over the 1994 Agreed Framework. The North believed that it had stuck to the agreement since it had capped and halted its plutonium-based nuclear program. That was all that was covered in the agreement. When the US did not seem to be pursuing its side of the agreement – by 2002, it was estimated that it was eight years behind schedule, while the new George W. Bush administration was showing signs of hostility – the North began pursuing an alternative route towards its original goal. If the administration had wanted, it could have raised its concerns quietly under the terms of the Agreed Framework, as the administration of President Bill Clinton had done. But eager "to confront evil", it chose a different path. It was not wise since it opened the way to the situation we have today. Yet the lesson was not learned, and agreements continued to founder because of a wish to add new conditions or to change the terms.

The United Kingdom had a more successful, if minor, experience. In the document establishing diplomatic relations signed in December 2012, it was clearly stated that we would be allowed secure communications as we did everywhere else. When I got to Pyongyang and raised the issue, I was told that North Korean law would not permit this. We could have telephone and fax communications, but no embassy or international organization could have access to the Internet. The World Food Programme, whose staff travelled all over the country, was particularly anxious for improved communications but had been regularly turned down.

In our case, the standoff continued for a year. I raised the issue on a regular basis, and North Korean officials visiting London were also bombarded with the same message. As I drew near the end of my time in Pyongyang, I thought I would try a different tack. Since I was going straight into retirement, I had nothing to lose! So one evening at my apartment where they had come for dinner, I told the European Department that they were running the risk that I would recommend to London that we abandon the idea of a resident embassy since we could not work as we were. The usual objections were aired but, perhaps by coincidence, a week later I was called aside at a party and told that we could have our communications. The Note authorizing this arrived the following day. As it happened, the budget was overspent so there was no change while I was there. But my successors benefitted as did other embassies and international organizations. And there has never been any attempt to go back on the agreement.

What Should Be Done?

For most of the period since 1945, North Korea has been seen as an awkward nuisance at best or as a potential source of trouble at worst. Rather than engage with it in the hope of effecting change, the way to handle it was to isolate it. In the light of where we are today, I find it hard to argue that such a policy was unsuccessful, especially given what happened during the short period (1998-2002) when South Korea and the US followed a different approach. Yes, it cost money but there were real achievements. A nuclear program was capped. The South began to build a new relationship with its neighbor, as did the US and many other countries. Even Japan began to benefit. Nobody got all they wanted from the better relationship, but it was the start of a process. If the momentum had been kept up, who knows where it might have led? The developments in 2018, the moving away from the threats and counter-threats of 2017, offer a glimmer of hope. Moving away from sanctions would benefit ordinary North Koreans as would the development of trading and other links. Rather than isolating the North, some of the effort that goes into implementing sanctions would be better used in providing training and opportunities to see how things are done elsewhere. Kim Jong Un has shown an interest in getting away from confrontation. Perhaps we should build on that.

Japan SPOTLIGHT March/April 2019 Issue (Published on March 10, 2019)

(2019/04/17)

James E. Hoare

Dr. James E. Hoare has a Ph.D. in Japanese History and joined the Research Department of the British Foreign Office in 1969. He was posted to Seoul, Beijing and Pyongyang. He now writes and broadcasts.

Japan SPOTLIGHT

- Coffee Cultures of Japan & India

- 2025/01/27