HOME > Japan SPOTLIGHT > Article

Interview with Dr. Hiromi Murakami, Visiting Senior Fellow of the Global Health Innovation Policy Program at the National Graduate Institute for Policy Studies (GRIPS) & President of the Japan Institute for Social Innovation and Entrepreneurship (JSIE)

Women in Japan Not Yet Fully Utilized for Economic Growth

By Japan SPOTLIGHT

In spite of the Japanese government's efforts to raise women's participation in social and business activities as well as public policy in recent years to encourage diversity in society, Japan ranks 110th out of 149 countries in the World Economic Forum's Global Gender Gap Index 2018. Women earn 25.7% less in wages than do men and only 3% of women hold senior management positions in central government, while the OECD average is 32%. The Japanese government believed that encouraging women to get into business would lead to raising productivity, as women, on average, are more intelligent than men on the basis of academic achievements at school. But, in reality, little progress seems to have been achieved in promoting women's roles in society.

Japan SPOTLIGHT interviewed Dr. Hiromi Murakami, visiting senior fellow of the Global Health Innovation Policy Program at the National Graduate Institute for Policy Studies (GRIPS), and the founder and president of the Japan Institute for Social Innovation and Entrepreneurship (JSIE), which is working on encouraging women in Japan to bridge this gap.

Introduction

JS: First of all, could you please briefly introduce yourself and in particular how you founded the JSIE?

Murakami: After graduating from university in Japan, I started working for a Japanese company. At that time I never dreamt about spending so many years overseas, though I had lived abroad for two years while my father was stationed overseas when I was a junior high-school student. After working for the company for a few years, I wanted to go and study an MBA just like my male colleagues, by taking advantage of its training program available for employees and asked my boss if I could do so. I was told that the company would not send women to business schools as female employees usually quit after having a child or getting married. Even though the Equal Employment Opportunity Law was already put into practice, I realized clearly that gender discrimination remained.

So instead of asking the company to send me over to an American business school, I decided to go and study there on my own. After finishing business courses in the United States, I was given an opportunity to go to a French business school as an exchange student, and then worked for a German company. Having lived in France and Germany, and looking at Asia from there, I realized I wanted to study further about Japan and Asia from political, economic, and geopolitical perspectives. Then I moved to Washington D.C. and there studied international relations at a graduate school and found a researcher position at a think-tank. I loved my job at the think-tank and worked there while pursuing doctorate studies. Eventually, I ended up staying outside Japan for 21 years in total, including my two-year junior high-school days.

Having lived and worked in the US and Europe for a long time, I found that Japanese women are not given full chances to maximize their potential, as Japanese women are still expected to assume the traditional role of women in a society. Preoccupations with conservative ideas about the role of women in a society still heavily prevail in Japan, and women are trapped in a marginalized world where they feel they have so many limitations. Japanese women simply don't see that chances exist in front of them or dismiss them in the belief that they are not for them. When I moved back to Washington again when my husband was assigned to a post there, I founded the JSIE in 2015 in Washington with a mission to realize Japanese women, young people and other minority groups' greatest potential and let them see the true opportunities they are entitled to. We are bringing inspiration and stimulus to awaken them from their marginalized world and to unlock their full potential as leaders.

JSIE Program

JS: The JSIE is still relatively new. How many people are working for it? What kind of activities are you doing?

Murakami: The core members are three Japanese women who have worked or studied overseas and share a sense of urgency that something needs to be done to change the mindset of Japanese women. We have four principal activities.

The first is the "Women's Initiative for Sustainable Empowerment (WISE) Program in Japan" that was started in the summer of 2015. The inaugural WISE program was modeled on Washington-style symposiums or conferences organized by think-tanks, with ex-government officials or top business leaders as panelists, where anybody in the audience can ask them any question. We wanted to create such an opportunity which had never existed in Japan where anybody can directly interact with these opinion leaders, who some in the audience might consider their role model and would like to emulate. Our very special guest was Carmen Lomellin, former US ambassador to the Organization of American States (OAS) during the administration of President Barack Obama, and Izumi Kobayashi, former president of Merrill Lynch Japan Securities and deputy secretary of the Japan Committee for Economic Development, and other distinguished American and Japanese women, including Margot Carrington, minister at the US Embassy in Japan in charge of public relations and cultural exchange also joined our panel discussions. The program attracted many talented female participants as the conference was organized in English. I was impressed by their enthusiasm and strong interest in talking with those leaders. Since then we have been organizing WISE every year.

The second is the "Washington Women's Dialogue (WWD)". Our first speaker was Aiko Shimajiri, then minister of state for Okinawa and the Northern Territories, as well as for space policy, when she visited Washington at the end of 2015. Having heard that she wanted to talk with Japanese women in Washington, we organized a dialogue with her and professional Japanese women working in the area. Since then, we have organized such dialogues 18 times so far, inviting role models to share their experience regardless of nationality, and each has attracted working women in Washington.

The third is the "First Movers Forum" aimed at encouraging people to have an entrepreneurial spirit and to think and act on their own. We invite young entrepreneurs in Japan as speakers to this forum several times a year. In Japan, working for a large company is still generally regarded as more prestigious and respectable rather than starting up a business of one's own. But there are nonetheless many attractive and creative entrepreneurs today in Japan, who are making an impact on society. This forum series features such "first movers" and presents the different perspectives and new social values they envision, as well as providing an opportunity for the participants to talk with them and be inspired by their experiences.

Finally, we have our "Global Peer Mentoring Network", an online program. In the US, there are various mentoring networks for working women, but such networks rarely exist in Japan for providing advice or consultations for working women. It is quite different from Japan that in the US there are many senior professionals, whether entrepreneurs or corporate leaders or high-ranking government officials, who are willing to offer advice to younger professionals. Therefore, we thought it would be helpful to organize an online network with these possible mentors and connect them with people who express their interest, for example, in working for an international organization and would like to talk to those professionals who have gone through similar career paths.

JS: Your programs seem to have gained positive responses. Are there any specific positive consequences starting to emerge from among the participants?

Murakami: From the second year, we started to focus on supporting social entrepreneurs with a relatively small number of participants at our annual WISE program. Among those participants, two women have started up their own businesses. We would like to support them to become success stories. Among our non-Japanese supporters, there are many interested in supporting Japanese women entrepreneurs as all of them pointed out that Japanese women are the most underutilized but have great potential for making an impact, and so the JSIE is now getting a variety of inquiries.

In the beginning, we were not well known and had difficulty even finding venues for events. But as our activities have continued and gained a good reputation we find an increasing number of people asking us to come and hold an event in different regions. In 2019, we will have two WISE events, one supported by the Kumamoto Prefectural government (Kumamoto WISE https://www.jsie.net/en/archives/6424/ on May 18-19, 2019) and the other co-sponsored by Ritsumeikan Asia Pacific University in Beppu in Oita Prefecture (Beppu WISE https://www.jsie.net/en/archives/5598/ on Aug. 2-4, 2019). So the positive consequences for us are that it is increasingly easy for us to gain support from partnering institutions and to acquire talented mentors and participants who are willing to join our WISE program.

Low Profile in Society & Business for Japanese Women

JS: In spite of efforts by the government and business corporations in Japan, Japanese women's participation in social and business activities remains insignificant. What do you think are the reasons?

Murakami: I think gender discrimination is still predominant in Japan. After having lived and worked in the US and Europe for so many years, in coming back to Japan I suddenly started to feel ill at ease. There are still traditional values prevailing about the role of women in Japan, namely working as a housewife and mother to keep their home happy and comfortable for their husbands and children. Those stereotyped values are naturally embedded in a variety of output from the media, and wherever you go you can find people who talk and behave unconsciously based on those values. For example, in a spontaneous conversation many would ask, "When are you going to get married?" or say "You cannot get married if you go to a graduate school." In an interview for a job, I hope that a woman might no longer be asked if she would quit the job if she has a child. The human resource department managers tend to assume women quit the company as soon as they have children, even though those women have no idea if they will ever get married.

Japanese society is such a society dominated by stereotypes and men and women both seem to be constrained by these thoughts and values. Women's freedom of choice is extremely limited under these circumstances whenever they may have to make a crucial decision in their life, such as choosing a job.

To tell the truth, we were shocked to see in one of our WWD meetings in Washington a young Japanese lady saying that her first priority in life would be to find a good husband and asking us how this could be done. Even such a young bilingual lady who had graduated from a top-level university with the aim of working internationally was not immune to the Japanese stereotype. There was another woman who said she would like to choose a job that could respond flexibly to her future husband's requests, namely she would prefer a job that she could adjust to easily in order to help her busy husband concentrate on his job. These women had started thinking about what Japanese men would not need to think about at all. We found it quite disappointing, since their thoughts were restricted by the Japanese stereotype on gender.

We have more than 200 Japanese women registered in the JSIE mailing list in the Washington area. All are not only bilingual but also very competent. The reason they are leaving Japan and working in Washington is that they would have more opportunities and fewer risks of being gender-discriminated against in the US than in Japan. It is truly unfortunate for Japan that it fails to utilize such invaluable talented pools of resources.

Changes on the Horizon?

JS: Even among men, until the 1980s those who devoted themselves to traditional office life, doing whatever their boss told them to do without complaint, were highly appreciated in business. But since the 1990s, we cannot expect to achieve growth simply by this method, and more innovative people who do not mind opposing their bosses now seem to be appreciated. Is this change starting to transform corporate culture?

Murakami: No, I do not think so. Corporate systems on personnel issues such as recruitment or an employee's performance assessment or incentives for working do not seem to have changed at all, since Japanese business people's mentality is still dominated by stereotypes of the ideal employee or the role of men and women. For example, until very recently, in a Japanese classified job section, there would be mentioned an upper age limit for recruitment, like only 35 years old. Even now, without such age limits, we still find spaces on CVs to be submitted to a company requiring the applicant's age and photo. I believe continuing such a custom is proof that Japanese corporations still cling to their old preconceived ideas about age and gender, and this can be considered a serious negligence.

During these 30 years since the burst of the bubble economy early in the 1990s, although there was a temporary reform by the administration of Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi during that period, Japanese companies have remained preoccupied by their memories of success in the past and their job assessment for promotion has been kept the same as it was in spite of globalization and a significant economic structural change in progress since the 1980s. When I was working for the US think-tank at the end of the 1990s I had a chance to interview top Japanese business leaders. One business leader told me that the Japanese economy would be restored when real estate prices rise back to their previous levels and the good old prosperous days return, so we just have to wait. I remember thinking there were very few who were aware of the urgent need for the fundamental transformation of the Japanese system that consists of seniority-based lifetime employment. This failure to acknowledge the need for reform imposes significant costs on our current society, economy, industries, and governance.

On the issue of policies to mitigate deflationary impacts, the Japanese government has chiefly been working on building up public and private investment while maintaining the system to feed into overproduction, the same as in the past. It should have started substantially investing in human resources. It is a great pity that we have not been sufficiently investing in education since the burst of the bubble economy, but I believe it is still not too late to do so now.

JS: But Japanese corporate culture seems to be changing in favor of raising diversity of human resources. Many large companies generally preoccupied with conservative ideas in Japan are now losing confidence in the usual business methods and are trying to get more women and non-Japanese among their board members.

Murakami: Unfortunately, such efforts have not yet achieved positive outcomes. The data show it clearly. In the central government, the percentage of female senior officials in positions such as director-general and deputy director-general is only 3% and in terms of the number of female senior managers Japan ranks as one of the lowest in the world. This is, I believe, the result of the reality of the Japanese business world where evaluation of the business performance of employees in line with values made by men and for men. With only 2-3% of women on boards, there is no diversity in business decision-making. Merely speaking about diversity and taking no action – this is our reality.

Entrepreneurship in Japan

JS: I guess today the best and brightest of young Japanese, regardless of gender, are increasingly interested in starting up their own business rather than getting a job at a large company with a seniority system. There seem to be in particular natural science majors emerging among the IT and biotech ventures. Will this be a trend in the future?

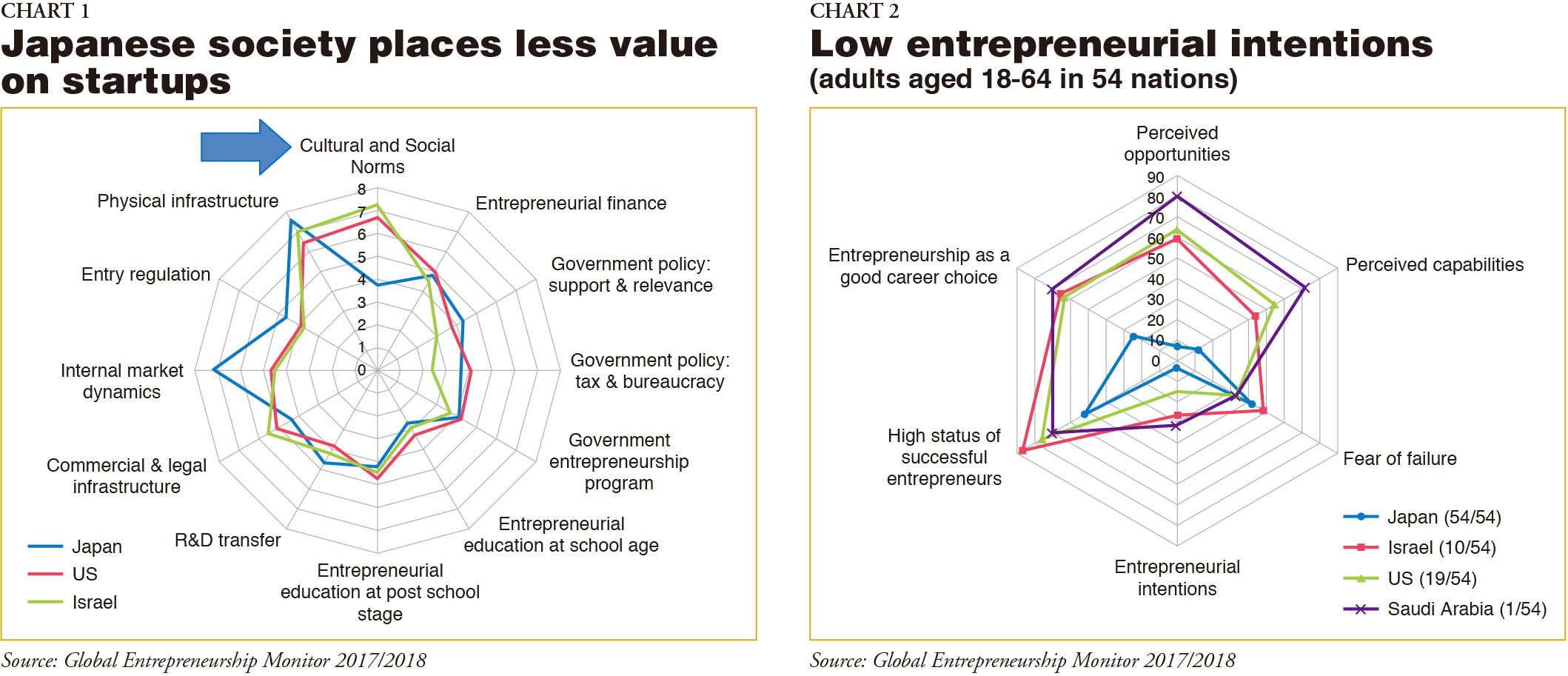

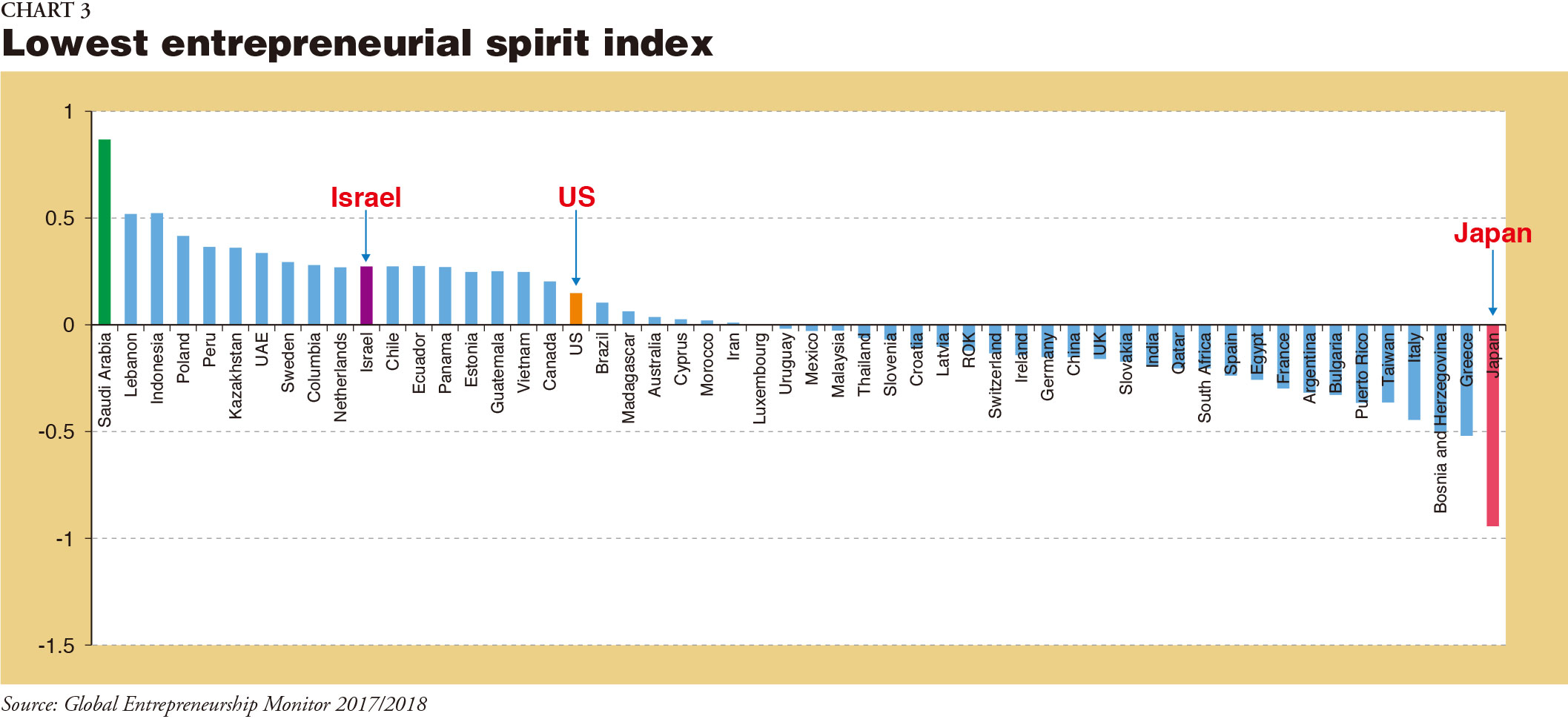

Murakami: I hope young entrepreneurs will be an engine for the Japanese economy, but I must tell you their business environment is very severe. Their social acceptance and entrepreneurial spirit index is much lower than in other countries among the indicators on entrepreneurship surveyed in an international comparison published in 2018 (Charts 1, 2 & 3). In other words, Japanese society is most reluctant to acknowledge entrepreneurs' efforts and achievements, and individuals neither see perceived opportunities nor entrepreneurship as a good career choice. This makes a significant difference from the rest of the world. Even though early entrepreneurial education is considered to be important, early Japanese education is not working either for encouraging creativity. A school teacher in Japan would not like a student trying to do anything that is outside the school rules. Everything is not allowed, except for a few things, so kids have to ask permission all the time. With such education, an entrepreneurial spirit would not be easily developed. The few emerging entrepreneurs you mentioned must be not the elite mainstream students in Japan but people estranged from the conventional Japanese school frameworks.

Financial support for ventures will also not be well accommodated in Japan. Fund raising is extremely difficult for ventures. Their management will face stumbling blocks unless they can secure funds to continue their business, and even if they won a million yen in prize money for their innovative products or services it would not be sufficient. The JSIE, our organization, is a social entrepreneurship company and we always find it difficult to secure a sufficient budget for activities, while every year we are asking for grants from foundations or the government. This is a big difference from the US where non-profit sectors often undertake government tasks, as in the form of the third sector over plural fiscal years. In Japan, foundation grants alone are available though limited, and it is considered typical that non-profit social projects suffer a chronic shortage of money, and therefore their activities are often not sustainable, even though their projects are helping local communities for public purposes.

I would like the Japanese government and people to think about new schemes providing a sustainable fund flow from the public sector to social entrepreneurs to undertake certain projects. By giving the right incentives, I think Japan can eventually be an entrepreneurship-friendly country.

Other Issues

JS I think Japan should have more contract-oriented jobs in which individual values and skills and incentives can be respected in order to enhance the happiness of each employee. What do you think?

Murakami: Yes, I think so, too. When I was working for a foreign-affiliated company, I found my work contract functioned very well. In accordance with the contract, every year I talked with the management about "what capabilities I have and how I can contribute them to the company's activities" or "what I would like to achieve this year based on the company's expectations" or "what would be beneficial for both of us given the company's mission or activities and personal goals". We concluded a new contract reflecting this conversation and on the agreed-upon contract we reviewed them at the end of the year, what was achieved and what was not, then discuss what can we do better. We could accept even a wage decline or additional training based on this review. I think it would be better for Japanese companies to follow this kind of consent-based model.

With this, job descriptions are clearly defined and this will help both company and employees to fairly evaluate job performance. It is important for both sides to agree upon the company's expectations as well as the employee's rights and responsibilities. That will help people with clear understandings about their tasks and make people work with greater satisfaction.

JS: As the number of non-Japanese employees will increase in the future, do you think such diversity will change the Japanese working style?

Murakami: Yes. I think we have a good chance to get the best and brightest foreign workers in Japan, as the US is now restricting immigration. Foreign workers will expect a fair and transparent assessment of their job performance, so their labor contracts will need to be clear and fair. Collusive agreements, often seen in Japan, will not work well anymore and instead all the aspects of a labor contract will need to be clarified and explicitly written. With this, Japanese women who left Japan to work or study abroad may be tempted to come back to Japan and would bring a strong degree of competence and true diversity to Japanese business.

In most of the years after 1988, the ratio of university entrants (including entrants into short-cycle colleges) to the total number of those who have finished their compulsory education has been higher among women than men. So it would be disastrously wasteful for the Japanese economy if competent women remain discriminated against or misjudged and deprived of good job opportunities. This situation could be substantially altered by a change in job performance assessments. I hope Japanese men will really help to realize such a wonderful result.

Japan SPOTLIGHT May/June 2019 Issue (Published on May 10, 2019)

(2019/06/12)

Japan SPOTLIGHT

Written with the cooperation of Naoko Sakai who is a freelance writer.

Japan SPOTLIGHT

- Coffee Cultures of Japan & India

- 2025/01/27