HOME > Japan SPOTLIGHT > Article

Interview with Jitsuro Terashima, Chairman of the Japan Research Institute

Outlook for the Aging Society in Japan

By Japan SPOTLIGHT

Japan is often referred to as a nation moving towards a superaging society at an unprecedentedly high speed. The majority of aged people in Japan, now and in the near future, were working full-time during the 1960s to 1980s, the so-called High Economic Growth Era in Japan. So they would have been influenced by the social and economic background of this era. What has made them feel so isolated and frustrated now? Gerontology is the study of the social, cultural, psychological, cognitive and biological aspects of aging. Maybe this multidisciplinary approach can provide answers to these questions.

Jitsuro Terashima, chairman of the Japan Research Institute, a Japanese think-tank that covers a range of policy issues, and president of Tama University in Tokyo, has recently been working on this issue and has published a book on gerontology. He was a senior executive of Mitsui & Co., Ltd. and has been involved in a wide range of public policy discussions as a policy advisor to the Japanese government for a long time, at the same time working as an academic on economic and social policy. Thus he is in a unique position to consider policy issues from the three angles of business, government and academia. His remarks in an interview with Japan SPOTLIGHT are summarized below.

Introduction

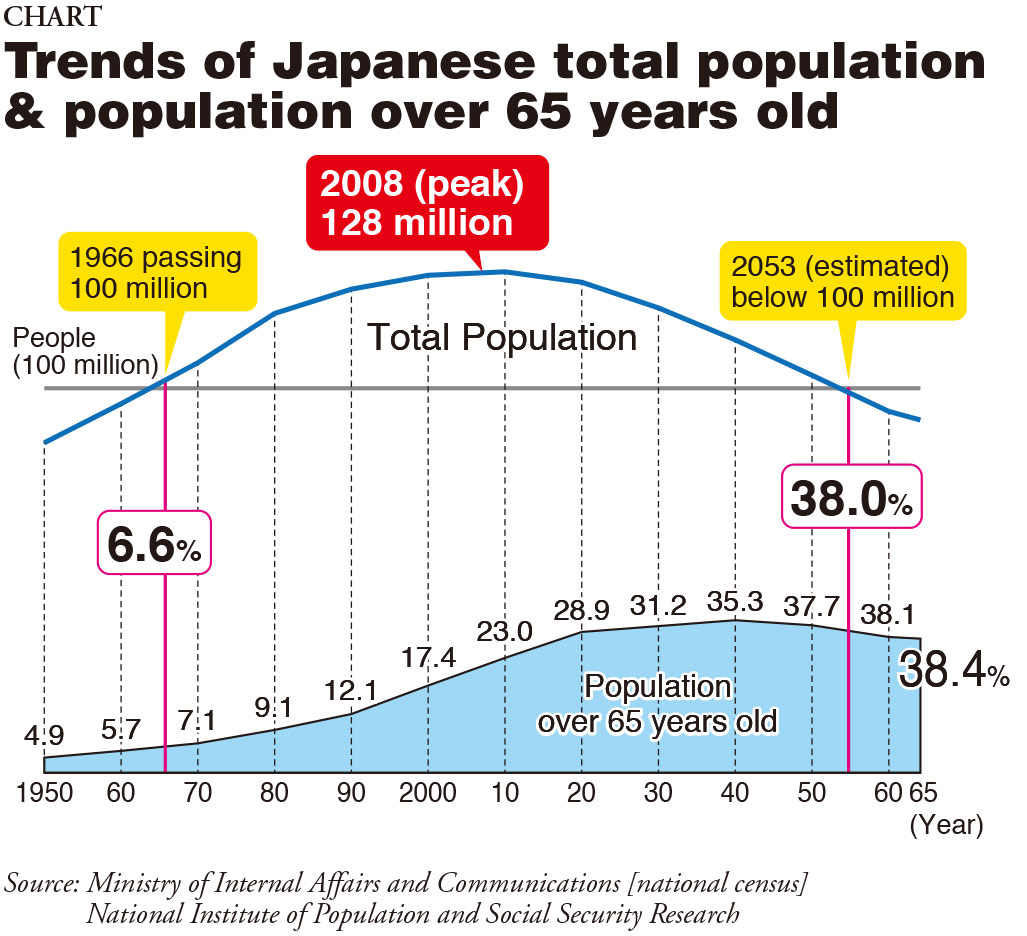

Japan is moving towards an aging society at a speed which no other country has ever experienced or will in the near future. The Japanese population was 43 million at the beginning of the 20th century and 100 years later had tripled. In 2008, it peaked after having reached 128 million and, according to one prediction, around 2100 it will have declined to 60 million, half of the population at the beginning of this century.

Meanwhile, the world population is predicted by the United Nations to increase to almost 12 billion by 2100 from 7.5 billion now. Thus while the world population will grow explosively, the Japanese population will shrink. A declining population may not necessarily mean the decline of a nation, but we will nonetheless need to find ways to stop the country from declining in such circumstances. We must also understand that it will not be easy to draw up a blueprint to enable Japan to maintain its high profile and contributions to the world.

In my recently published Japanese book titled Gerontology Sengen (Declaration for Promoting Gerontology), I referred to the fact Japan is seeing not only a decline in population but also aging on an extraordinary scale. In 1966, two years after the Tokyo Olympics, when the Japanese population exceeded 100 million, the population over the age of 65 was only 6.6 million – in other words, about 6.6% of the total (Chart). But after 2050, when we predict that the Japanese population will be less than 100 million, the population over the age of 65 will be around 38 million – a percentage of around 38%. Taking 100 years as an average life span in the future thanks to significant advances in medical science, we have to assume that the average Japanese will live another 40 years after retirement at the age of 60, which is still the retirement age adopted by a large number of Japanese companies.

Up until now, all kinds of policy discussions in Japan concerning the aging society have focused on the increasingly heavy social costs, such as pensions, caregiving, and insurance, and how we could deal with them. The reason why I started discussions on gerontology and how aged people could contribute to society is that I believe we are now at a turning point where we should start planning new social institutions to respond to the question of how older people can support the aging society rather than how younger people can support the aged. In a society where the proportion of aged people reaches nearly 40%, it is impossible for the younger generation to support so many elderly. Even now, 70% of people at the age of 80 are in good health. So it will be important to create a platform where people even at the age of 80 would be able to support society. We will have to think about how to encourage the aged and women to work and participate in social activities more earnestly. Gerontology can help provide us with the capacity to plan based on social science as well as policy science in order to achieve it.

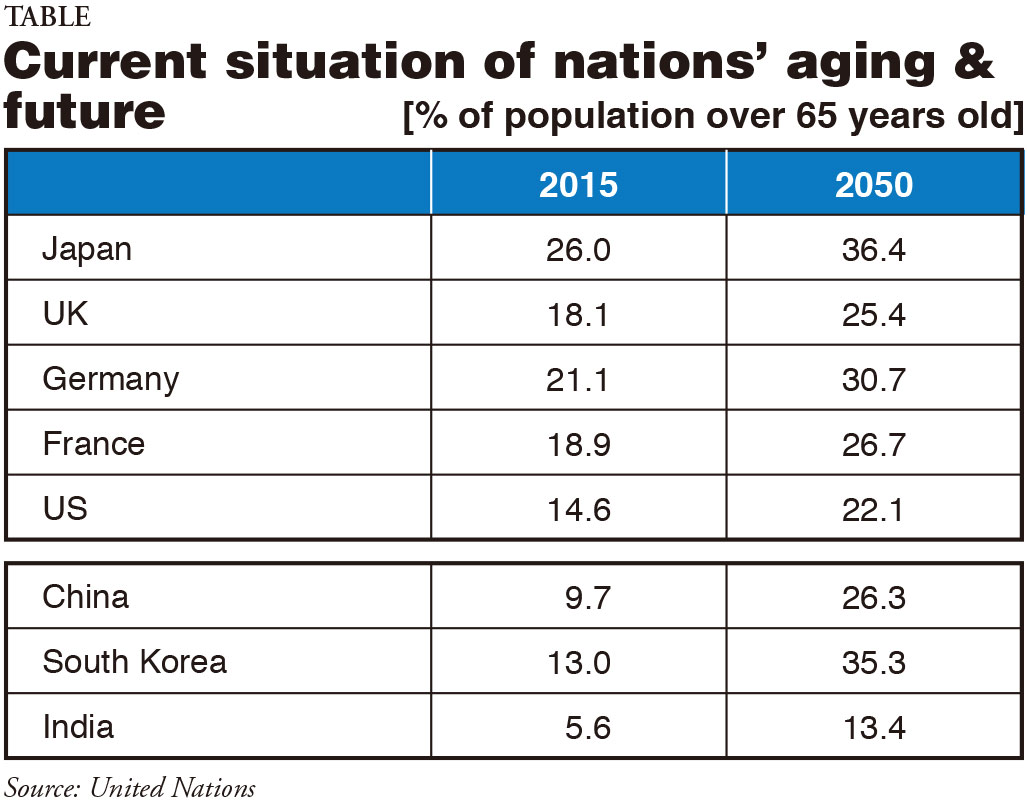

It is clear that Japan is experiencing aging at the highest speed and on the largest scale now in the world (Table). South Korea and China, sooner or later, will catch up with Japan and become aged societies as well. So the lessons Japan learns from gerontology could be crucial for social and economic stability in East Asia. The key to success will be how we can create a platform for senior people's social participation.

Aging Society Expanding in the Suburbs

Another point that I would like to mention is that life for the elderly in the suburbs of post-industrial Japan will be very different from that in an agricultural society. In the postwar period, Japan became an affluent nation by earning foreign currency through exports of its industrial goods while importing food and natural resources from overseas – this having been considered the most efficient way to achieve wealth. It was not wrong to do so by building up industries like steel, electronics and automobiles in the painful process of economic restoration after defeat in World War II. But this process resulted in the concentration of industries and populations in large cities and lowered the food self-sufficiency ratio to only 38%. Moreover, what is now going on is that the people who supported this process, including the baby boomers, are all becoming aged and have made their homes in concrete blocks in the suburbs of large cities. The most efficient way for them to live after retirement was thought to be to live in one of these apartments, or even luxury ones, in the suburbs of large cities. Thus, buying a luxury apartment with a bank loan and paying it off by retirement age was said to be the typical success story for a man earning a salary from a company. So a large number of people are now living there as senior citizens.

In the case of an agricultural society, the senior citizens live very close to primary industries, such as farming or fishing, and find it easier to participate somehow in social activities related to them, even though they are getting old and losing their physical vitality as well as willingness to work. By contrast, the aging society in the suburbs of large cities, surrounded by concrete blocks, would have a zero food self-sufficiency ratio. Assuming that the proximity of food and agriculture to the place of living is related to human happiness, the distance between them increases anxiety.

I recently met the chairperson of the American Association of Retired Persons (AARP) in Washington, D.C., which helps organizes affairs for 36 million retired people all over the United States. There is no organization like this in Japan. After retirement, most of the Japanese employees living in the suburbs of large cities leave the labor union and live independently, neither organized nor integrated into a human network, but with only their memories of having worked for a company. In other words, they tend to be isolated easily. Besides this loneliness in their psychological situation, they may also experience a lack of agriculture or religion in their urban life.

On religion, for example, they may have visited the cemetery of the temples where their parents and ancestors are buried or taken part in a summer festival at a shrine in their neighborhood. But they may not have questioned themselves more deeply about how they should tackle their concerns about life, which is a fundamental and essential part of a religion. This lack of religious life might cause them to panic and fear that they could not manage by themselves if they suffered from a terminal cancer. Elderly people who have not already thought deeply about life and death might not be able to maintain self-control. After hearing from a doctor that they were at the final stage of cancer and would not be able to live another three months, they might panic and become aggressive towards nurses, or bother doctors by asking insistently questions like "What happens to us after death?" So hospitals would then have to employ clinical psychologists to deal with such patients and today even clinical religion teachers are important. They are expected to tell patients at a terminal stage how to face death. Occasionally, distinguished priests play this role.

Such challenges for the aging society in Japan are the result of an industry-oriented economic development model completed in the postwar period. This model enriched the country materially but not mentally. Japan is becoming a large-scale aging society having lost its mental affluence. This could cause serious issues. Therefore, through gerontology, the study of the use of elderly people's capabilities, we must create a social system where senior citizens recognize that human beings are social animals and affirm their social relations and contributions to society as they get older.

According to one analysis, if people after retiring at 60 live in their concrete blocks in the suburbs of big cities for many years, whether they are couples or singles, 70% of them will become mentally ill by the age of 80. Already there are some who aggressively and repeatedly call the local administrative offices to make complaints. More than 70% of them are over 70 and many of them are former company executives.

Building Platforms for Social Participation

My work in gerontology is not superficial – such as how to encourage senior citizens in Japan to work longer – but attempts to analyze what kind of people have been raised against the economic and social background of the postwar period and how we can encourage greater social participation for the elderly in our aging society.

To be more specific, we founded the Research Council of Gerontology and there we are actively discussing how to maintain Japan's vitality. Among the issues discussed so far, tourism has attracted growing attention. In 2018, the number of inbound tourist arrivals in Japan exceeded 31 million and 80% of them were Asians. In my view, the type of tourist will change in the future. From a global perspective, in a country with GDP of more than $5,000 per capita, interest in overseas travel would grow, and with more than $15,000 per capita, overseas trips would change from group tours to personal or family trips.

This means we will see a change in the nature of Chinese visitors soon, as Chinese per capita GDP reached nearly $10,000 in 2018 and will probably be closer to $15,000 in the near future. Chinese tourists have come to Japan so far mostly on group tours to purchase many things in large quantities, but when their per capita GDP passes $15,000, they may turn to more personal objectives in their visits to Japan, such as family trips involving renting a car. Japan could offer medical tourism, history tourism or industrial tourism as high-end goals, and in such cases we would need more high-end tourism professionals to provide useful information for such individual visitors. These professionals would need advanced linguistic skills and rich international experience. For this purpose, we could organize a network among the elderly living in the suburbs of big cities and establish a qualification exam to assess their language skills in either English or Chinese, for example, or their knowledge of Japanese history. We could then create a platform for people who have a number of skills that senior citizens could participate in. Young people would prefer to earn money by working rather than people's appreciation, but the increasing number of elderly people would prefer social acknowledgement of their work as a contribution to society rather than whatever money they might earn. So it would be very significant if this enabled the elderly to work as professionals in high-end tourism.

In terms of Japan's relations with the rest of Asia, if we can increase the number of Asians interacting with the Japanese through networking it could help revitalize the Japanese economy. Whether Hokkaido, the northern island of Japan, prospers or not would depend on how many people who do not actually live there but in Tokyo or the rest of the world can interact with the residents and enhance their contribution to the local economy through networking.

Another possible platform for encouraging older people's social participation would be in raising children and education. The administrations in each region should take the initiative to encourage elderly and knowledgeable persons to participate in projects to raise children as a whole community.

There is also the area of food and agriculture. I know of a group of elderly people living in Yokohama who are helping an apple farm in Nagano to produce apples. At first, with no one to take over the farm in Nagano, 20 to 30 people who live in apartments in Yokohama got to know about it and started going to the Nagano farm and engaged in producing apples there. Among them were people who had formerly worked as accountants or for trading companies in marketing and business development. All of them took advantage of their professional experience in the past in working for the apple farm. Now, having had technical lessons at the apple farm, they have learned to produce jam and juice from the apples, and they now produce vegetables as well.

At Tama University, they organized a project for rice production from planting to harvesting for older residents in the Tama area of Tokyo, with the university providing bus transportation for them. The participants are delighted to see what they produce and this is an enriching experience for them. That is one way in which gerontology can help address the seeming emptiness of an aging society.

Revitalizing Intelligence Among the Generations

In thinking about an ideal aging society, I believe that revitalizing three groups among the generations will be necessary. The first is the group aged from 18 – high-school graduates – until graduation from university or graduate school. We will need to improve the scope of knowledge they can acquire through advanced education and address the particular needs of the new age.

The greater challenge at the moment, however, is with the generation in their late 30s to early 50s, the parents of the first generation. They have been living in an era of continuous economic decline in Japan after a peak around the year 1990. In 1997, the annual disposable household income of Japanese salaried workers topped out and it has been declining since then by at least 400,000 yen during these two decades. So even if there had been no growth in disposable income, people in this generation coming closer to the elderly group would have been able to save around an extra 8-10 million yen on average to prepare for an aging society. In addition, while baby boomers had spent their young days during the Japanese economy continuously progressing and were able to pursue their dreams by synchronizing their own development with their companies' growth, the Japanese in their 40s have not been given such dreams in a continuously deflationary economy, even among businessmen promoted to be directors at the core management of their companies, despite working earnestly on their specialties and supporting specific sections in their companies. So it is not an overstatement to say they have never had the experience of seeing dreams come true. With little in savings and without having realized any dream, they remain very unhappy.

So this generation will need to consider whether what they learned 20 years ago at university will be relevant to them now. In the 21st century we have seen the deciphering of the human genome completed, while artificial intelligence (AI) and big data attract growing attention. With such technological innovations, the knowledge of social science acquired 20 years ago may be of little use in this revolutionary age. They will have to learn about these innovations by themselves in order to feel at ease.

For the third group among the generations – those aged over 60 – things will be fundamentally different. The intelligence needed for the younger generations is fluid intelligence, namely the ability to solve problems using logic; but for the older generations it will be crystallized intelligence, the ability to draw on one's knowledge and experience. Elderly people will suffer from declining memory, but with better crystallized intelligence they could find solutions to problems by analyzing their own rich experience. For example, if you have had numerous experiences of a broken heart in your life, you would be able to give helpful advice to a young broken-hearted person.

I would emphasize for this generation the importance of the theory from Buddhism that all existence is subjective and nothing exists outside of the mind, as we are coming closer to an age of AI. Machines will be appropriately judging the rationality of the means to achieve goals, and will always defeat a human being in this selection process, no matter how much effort human beings may make. But no matter how much AI advances, it will never be able to be moved by anything. There is a story told by an Italian AI expert about Apollo 11 when Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin became the first human beings to walk on the Moon in 1969. They saw the Earth rising in the sky over their module after they had landed and they burst into tears, overwhelmed by the thought of it and of where they were. This ability to weep cannot be replaced by any computer. This human thought that they had finally came to such a place so far away from their parents, wives, and friends whose faces instantly emerged in their mind is uniquely human and no machine could imitate it.

In other words, there is no logical rationality between means and goals in the human sense of beauty. For example, you would jump into the water to save a drowning girl before asking yourself if you could swim or not. You might drown if you cannot swim. But this could be interpreted as human aesthetics. Human beings would do their best not only for their own interest but for the persons they love. It is not too much to say that the quality or scale of your work may be determined by your respect for your boss. No computer would be able to replicate human aesthetics. The revitalizing of your intelligence will thus depend on your age and circumstances, as well as the nature of the challenges you face, rather than making efforts to increase your knowledge of the liberal arts.

It should also be noted that the concept of a "marginal person" will be key to preventing elderly and retired people in the suburbs of big cities from falling into solitude and unhappiness. Anybody working for a company should be positively valued by the company for their good work performance, so you should be an irreplaceable colleague. But this does not necessarily mean that you would have to devote all your time and energy to your company. It would be better to do many other activities outside your company, and then you could have an objective view and raise your value as an individual.

When I was working for Mitsui, I worked for a wide range of voluntary study groups outside the company across business, government, and academia, as well as the media. I was supporting a variety of business firms in their planning of business strategies. On the government side, I participated in policy discussions of advisory committees to the administration, including the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry and the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism, as well as in public projects. In academia, I was a visiting professor for a number of universities and built a synergy with business. I believe that we should keep an objective eye on our own company while working hard and devoting ourselves to it.

In Japan, some people feel they have little value as an individual after retirement and leaving their company. In order to avoid this, we should keep on revitalizing our intelligence. Unless we do so and maintain our own views on issues aside from our company's view, and reintegrate our working experience into theories based on those views, we will be unhappy eventually in an aging society.

Japan SPOTLIGHT July/August 2019 Issue (Published on July 10, 2019)

(2019/07/11)

Japan SPOTLIGHT

Written with the assistance of TapeRewrite Corporation.

Japan SPOTLIGHT

- Coffee Cultures of Japan & India

- 2025/01/27