HOME > Japan SPOTLIGHT > Article

Haiku Attunement & the "Aha" Moment

By Edward Levinson

As a photographer and writer living, working, and creating in Japan for 40 years, I like to think I know it well. However, since I am not an academic, the way I understand and interpret the culture is intrinsically visual. Smells and sounds also play a big part in creating my experiences and memories. In essence, my relationship with Japan is conducted making use of all the senses. And this is the perfect starting point for composing haiku.

Attunement to one's surroundings is important when making photographs, both as art and for my editorial projects on Japanese culture and travel. The power of the senses influences my essays and poetry as well. In haiku, with its short three-line form, the key to success is to capture and share the sensual nature of life, both physical and philosophical. For me, the so-called "aha" moment is the main ingredient for making a meaningful haiku.

People often comment that my photos and haiku create a feeling of nostalgia. An accomplished Japanese poet and friend living in Hokkaido, Noriko Nagaya, excitedly telephoned me one morning after reading my haiku book. Her insight was that my haiku visions were similar to the way I must see at the exact moment I take a photo. One of her favorites:

star shaped

pumpkin flowers

radiant humans

(Edward Levinson, Balloon on Fire, Cyberwit.net, India, 2019. Ibid for all other of the author's haiku.)

Nagaya sensed my haiku were captured in an instant and were seen and preserved the same way as my camera's eye. In this she is right. My haiku are not recorded as thoughts, but as sensory feelings that take me deeper into the wonder and symbolism of nature, the cycles and rhythms of the cosmos. Similar to what photographers call the "original capture", the special moment is first recorded in the heart, then developed into a visual word image on paper.

Most of my haiku come to me when my senses are in harmony with the surroundings, the mind preferably blank and receptive: quietly drinking a cup of tea, sitting or walking in nature, working in the garden, people watching, riding on trains, even driving.

The following spring haiku came to me while driving through the mountains on a misty wet day, as I was moving to start a new life in the Japanese countryside. Not wanting the heavily loaded van to lose momentum by stopping to jot down my thoughts, I kept repeating the poem like a mantra until I memorized it.

spring rain

washing heart

spirit's kiss

Later this haiku certainly surprised a Japanese TV reporter who was covering a "Haiku in English" meeting in Tokyo where I read it. Later it appeared on the evening news, an odd place to share my inner life.

Sharing has always been a part of haiku's history. The origin of haiku is entwined with renga poetry, which has a 700-year history. Renga poets collaborate on a poem by linking to and building upon the previous verses. The first 5-7-5 stanza of renga was called hokku and in Matsuo Bashō's era (1644–1694) it gradually became an independent poetic form. Renga was written as a group endeavor in contrast to haiku being written by an individual's experience. In the late 19th century, prolific poet Masaoka Shiki (1867–1902) began using the word "haiku" as the name for this stand-alone verse, as we currently know it. Shiki was influential in promoting the idea of haiku as shasei, "sketches of life", which is popular today. Here is just one of his 20,000 haiku:

get drunk, sleep

weep in a dream

mountain cherry blossoms

(Masaoka Shiki, The Shiki Zenshū Vol.11, Kōdansha, Tokyo 1975, in Japanese, above translation by author.)

Receptivity & the Unthinking Mind

When writing my haiku, the first image/word connections usually come to me in Japanese. I quickly scribble them down phonetically using the Romanized alphabet, following standard 5-7-5 syllable pattern, keeping to the rule of 17 syllables. Then I render them into English while working to make Japanese kanji versions more poetic. While not always exact translations, the English and Japanese haiku play off each other. On occasion English comes first or both versions come out simultaneously.

The original idea, the "aha" moment, is most often stimulated by a scene or image that inspires me. I call this process "Visual Stimulation and the Unthinking Mind". Some obvious sources of inspiration for haiku poets: nature, touching human relationships, societal problems, ironic or humorous juxtapositions, and encounters with art.

My first impression becomes the basis of the haiku. The thinking brain part, searching for the best words, creating a rhythm, polishing what I call the "punch line", come after the first vision in the unthinking mind.

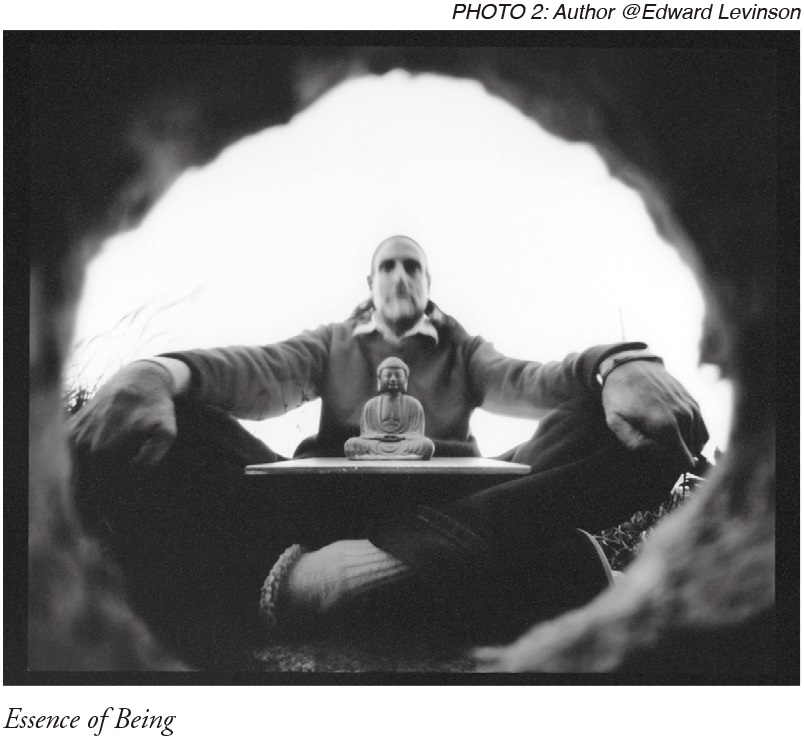

The popular image of Zen Meditation is to sit, concentrate on breathing and try to become empty. The empty space is conducive to being receptive; a heightened sense of awareness to one's surroundings is also a benefit. This is just one example of a practice that creates fertile ground for seeds of inspiration to sprout. Other formal meditation practices are just as valid, be they religious or any of the mindfulness techniques encouraged these days.

Kigo Seasonal Words

Traditional Japanese haiku nearly always include a seasonal word called kigo. In the haiku above it is "spring rain". Japanese season word dictionaries called saijiki help writers include one in their verse. Saijiki lists exist in English as well. My original inspirations usually include kigo, but I don't force them into the poem.

Since I am an avid gardener and also practice what I call Nature Meditation, using seasonal words mostly happens spontaneously without thinking. The sounds of the cicadas in summer easily stir up some poetic image. A winter cold north wind brings shivers, wakes you up, creates a feeling of the unknown. Cicada and north wind are standard kigo that every haiku writer from the most famous Bashō to school kids will likely use.

My translation of one of Bashō's famous cicada haiku, from The Narrow Road to the Deep North:

silence...

penetrating the stones

a cicada's voice

(Matsuo Basho, Oku no Hosomichi, originally published in 1702, various English translations available.)

And one of mine:

cicadas crying

heart worrying

can I succeed?

On the hot summer day when I wrote this, many upcoming fall projects were on my mind; the vibrating cicadas seemed to amplify my anxiety.

I like to do my morning breathing and attunement practices outside in nature as much as possible. It can be trying on cold winter days, but worth it for rewarding inspirations like this one, which received an Honorable Mention in the well-known Itoen Haiku Competition:

north wind

touches my shoulders

awakening dreams

Many of my haiku are written in the free-style. Not using kigo increases the possibility to universally share special moments. In this next irregular haiku, with no kigo and which also doesn't use the 5-7-5 pattern in the Japanese version, I hoped to bring some laughter to the reader by practicing the kokkei (sense of humor) style of haiku. But at the same time I try to convey some basic truth about life.

play in dirt, boy

work with dirt, man

sleep on dirt, dog

As haiku should be, it was born from a real life episode, a natural example of one of my lecture titles: "Writing Organically with Inspiration as the Seed." One day while babysitting a friend's young son, we were out in my vegetable garden at planting time. The boy was sitting in his innocent world playing in the dirt. I was working, digging diligently with my spade preparing the soil for seeds. My dog, tired of playing with the boy and not in the mood to dig, was peacefully sound asleep. Man, boy, and "man's best friend" linked in a moment.

Rather than intellectually include kigo, I prefer them to flow naturally into the context. Many haiku messages transcend seasons or appear on the boundaries of two seasons. Internationally some countries don't have four seasons, while the Nepal Haiku Society recognizes six seasons in their country for creating haiku. Japan is also said to have five if you add the rainy season.

Beyond Kigo

One of Japan's most respected modern haiku poets, Ban'ya Natsuishi, writes without regard for seasonal words, while inspired by personal, political and philosophical issues. Here is one of his haiku with a strong environmental message.

Where there was a tree

near the pure spring – –

the noise of saws

(Ban'ya Natsuishi, Endless Helix Haiku & Short Poems, Cyberwit.net, India, 2007. Ban'ya Natsuishi is the haiku pen name of Masayuki Inui.)

Natsuishi could have easily added a season word, but the impact is much greater as it is. One might at first think it is the "spring season", but "near the pure spring" implies natural spring water. It could also be a hidden reference to Rachel Carson's environmental warning described in Silent Spring. It creates a simple image, one that is universally understood and lets us decide the meaning.

In a literary commentary on Natsuishi's works Mary Barnet writes, "Haiku is not merely truth, it is wisdom coming from the juxtaposition of disparate realities." (Mary Barnet, At the Top: Haiku and Poetry of Ban'ya Natsuishi, p.10, Cyberwit.net., India, 2019)

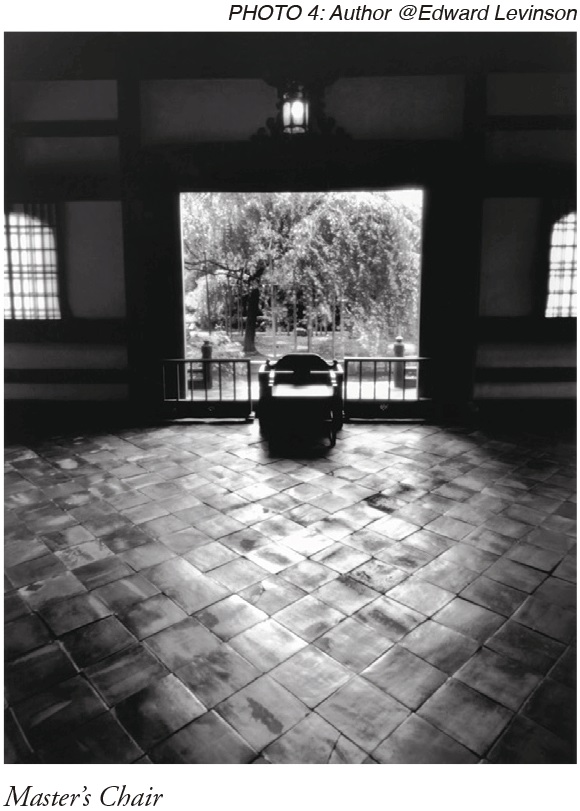

With a different mood, here is one of my haiku that also contains no season word:

window of light

on stone floor

Buddha appears

"Window of light/on stone floor" may imply a season where the angle of the sun is lower in the sky, but it is not really important to what I was feeling at Anrakuji Temple along the Ohenro 88 Temple Pilgrimage Route on Shikoku Island.

Universal Haiku

As a writer immersed in Japan and its culture I often wonder if certain of my haiku will only have meaning for Japanese readers and people familiar with Japanese culture. Does it have international appeal to bridge cultures? More importantly, can a personal haiku (with or without a kigo) have universal meaning and share something special with the world? Natsuishi's "noise of saws" certainly does.

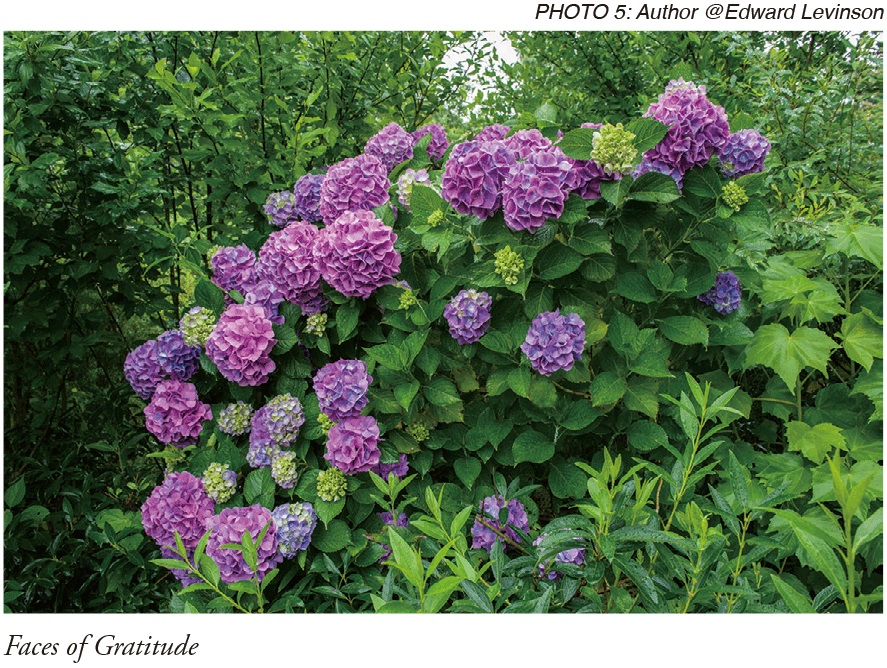

Most nature images will easily cross cultural boundaries. Consider this one of mine:

full of heaven's rain

heads bow to the earth...

hydrangea flowers

Hydrangea is a kigo easily recognized as "summer" in many places around the world. However, "full of heaven's rain" refers to the rainy season in Japan, which happens to be when the hydrangea are in full bloom. Regardless, it was the picture of "heads bowing to the earth with thanks for the rain" that inspired me and is universal in nature.

Participating in the 10th World Haiku Conference in Tokyo in 2019, I heard many of the international attendees baring their souls, sharing their experiences of life that easily transcended national and ethnic boundaries. Many included seasonal references from their own countries but just as many didn't. The following example, from a Moroccan poet, is likely a homage to Bashō's famous haiku – "old pond/ frog leaps in/sound of water":

A clear pond

The birds

Fly into the depths.

(Sameh Derouich, in World Haiku Conference Anthology, published by World Haiku Association, Japan, 2019, edited by Ban'ya Natsuishi.)

For Japanese haiku respecting the 5-7-5 pattern is important and adds necessary discipline to the "no kigo" style. Both traditional and modern Japanese haiku are actually written as one long line – not three short ones as in English. In Japanese language, the ear instinctively hears the 5-7-5 sections. The 17 syllables are called on: long vowels are counted as being two on and the ending "n" sound is also counted as one separate on in the 17 total count, increasing the need for brevity. However, rules allow for extra syllables when necessary.

The 5-7-5 pattern is not really practical in English and other languages. Using a short-long-short line form is one alternative, but with different languages having different word orders, this often doesn't work. However, in any language, the sound and rhythm of the haiku is important. I would like to see more emphasis on haiku as "spoken word" poetry that brings alive the writer's experience of a moment.

On Demand Inspiration

Ku-Kai are gatherings for haiku poets of all levels. They meet, compose, and share haiku upon a given theme or seasonal word. Sometimes the poems are written and polished in advance; sometimes they are composed on the spot. Constructive criticism is usually allowed and the best haiku of the day, selected by the teacher or group, are read aloud.

Writing haiku on demand is not my usual way to work. As noted, I prefer to go with the raw inspiration of a moment, but occasionally I will join such a meeting.

To my surprise I found I could come up with a good haiku using my imagination, creating a visual scene without really being there. But to do so, I must have a real memory or feeling for that word; the heart and mind still need to be calm and empty for something true to myself to come out.

So one rainy Sunday afternoon sitting around a table with a group of Japanese haiku hobbyists, I shut my eyes and focused on the group's theme image of takenoko, the summer seasonal word for "bamboo shoots" sprouting in a thicket and also a seasonal food delicacy for many.

confused on the path

bamboo shoots

show the way

The image is personal in tone and perhaps not immediately obvious to the casual reader. Tampered bamboo shoots, popping straight out of the ground, and pointing upwards like arrows, appeared in my mind's eye as symbolic markers guiding me on my path.

Sometime later I pulled from my bookshelf a slim volume of haiku by Kobayashi Issa (1763-1827), a famous poet of peasant background, and smiled when I found this one:

The daikon picker

points the way

...with his daikon

(Kobayashi Issa, in Inch By Inch 45 Haiku by Issa, translated by Nanao Sakaki, La Alameda Press, New Mexico, 1999.)

Photos & Haiku

Using photographs as stepping-stones into haiku is extremely popular in Japan especially on TV programs, blending their need for visual content with written shasei style life imagery. We can also see numerous examples of traveling photographers creating photographic essays to illustrate Bashō's famous walking journey to the North.

In the past I often did slideshow presentations with my nature photographs narrating them with Nature Meditation suggestions. Many people found it easier to meditate looking at images, which then led them into their own worlds. I was often asked which came first, the meditation theme or the photo. Truth is, the creative process goes both ways, and is the same when pairing photos with haiku.

One evening I took an abstract rain photo while sitting in the car at a shopping center. Back home, seeing the enlarged photo on the computer, I composed a caption for posting it on social media; without thinking, it came out naturally as a haiku. The photo moment came first; the haiku followed later after seeing the screen image but is based on a real life episode.

rainy night

waiting for you

tears of light

In another local experience, where admittedly the thinking mind slipped into the process, I contemplated the difference between the spring and fall sunsets. I was driving east towards home down the two-lane highway known as Nagasa Kaido (translated loosely as "The Long and Winding Road"). A red sunset ball in my rearview mirror seemed to hang there forever, like one of those red laser-pointer dots, following my actions, appearing as red catch lights on unsuspecting house windows and shimmering across water filled spring paddies.

In the fall, the sunset is short and sweet, to the point of being made into a well-known Japanese metaphor: Aki no yūhi, tsurube otoshi, "The fall sun sets as a bucket dropping [rapidly] into a well." (Tsurube otoshi – "dropping bucket" – is on the fall season word list).

Suddenly I wondered if there is an opposite image for a spring season, long-lasting sunset. My metaphor came out in the form of a haiku, with many photos to match it already in my archives!

spring sunset

floats freely

balloon on fire

Beyond the Image

In art and life, finding validation of one's own work by seeing the work of others is comforting. These three modern haiku are not "linked" on purpose; the authors are from different countries and backgrounds, writing on their own at different times, but they share the same theme.

Walking is philosophy's

best friend – –

voices from the clouds

(Ban'ya Natsuishi, Ibid, Endless Helix Haiku & Short Poems)

The window asks

Does the wise man know

I am the eye of eternity?

(Abdulkareem Kasid, Sarabad, Shearsman Books, UK, 2015. Kasid is an Iraqi poet living in the UK.)

a hole in the sky

the eye of God opens

I am seen

(Edo, haiku pen name of the author from the Japanese Megumi no Michi meaning "Road of Blessings").

Can we experience haiku as a conversation or prayer, in addition to the traditional idea of a painted word image? Is it simply a picture or is it a work of art? Are they personal experiences or universal feelings? Do we really need to intellectually think about it?

Following the path of both traditional and modern haiku, I want to watch, feel, and write naturally, to read and see the light of others. Through deceptively simple haiku I discover seasonal, spiritual, philosophical, humorous, and ironic epiphanies as well as our commonality.

feeling fine

running with my camera

mountain laughing

Note: The author's book Whisper of the Land was the subject of a Japan SPOTLIGHT interview in the Nov.-Dec. 2015 issue (https://www.jef.or.jp/journal/pdf/204th_Interview_03_xx.pdf). His books are available at www.edophoto.com and www.whisperoftheland.com

Japan SPOTLIGHT May/June 2020 Issue (Published on May 10, 2020)

(2020/06/17)

Edward Levinson

Edward Levinson is an award-winning photographer and short filmmaker, as well as an essayist and poet. He exhibits and publishes internationally; as a speaker he presents photo-illustrated talks on photography, creativity, and his unique experiences with Japanese culture. He is a member of The Photographic Society of Japan and The Japan P.E.N. Club. Living in Japan since 1979, he resides in Kamogawa, Chiba Prefecture, inspired by nature and Japanese culture.

Japan SPOTLIGHT

- Coffee Cultures of Japan & India

- 2025/01/27