HOME > Japan SPOTLIGHT > Article

Has Populism Peaked?

By Matthew Goodwin

Introduction

In recent years, the rise of populism has been one of the most striking aspects of contemporary politics. The arrival of figures such as Donald Trump in the United States, Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil, Matteo Salvini in Italy, Marine Le Pen in France and Nigel Farage in the United Kingdom has triggered global debates about the health of liberal democracy, thrown light on the "losers of globalization" and questioned the long-term survival of mainstream political parties and ideologies.

Despite variations in support from one country to another, at a broad level this "family" of political parties has put down deep roots. It has prospered from social and economic divides that were a long time coming and which may be exacerbated by the unfolding Covid-19 crisis. In short, I will argue that whereas the 1980s and 1990s saw the electoral rise of these parties, the 2000s and 2010s have witnessed their consolidation in many political systems. National populism, put simply, is here to stay and will continue to influence global debates about trade, taxation, supply chains, redistribution and, increasingly, the role of China in the world order. This essay shall begin by defining what we mean by "national populism" before charting its electoral rise and consolidation, and then conclude by reflecting on the potential impact of the current Covid-19 crisis.

What Is National Populism?

National populism as a movement is not just about political protest or one single issue, such as immigration. The definition Roger Eatwell and I give in our book National Populism: The Revolt Against Liberal Democracy (Penguin, 2018), is that national populism seeks to "prioritize the culture and interests of the nation, and promises to give voice to a people who feel that they have been neglected, even held in contempt, by distant and often corrupt elites". As part of a broader quest to give voice to a neglected people, national populists typically favor "direct" rather than "liberal" conceptions of democracy; they want to prioritize the majority popular will, such as through the use of referendums, over individual and minority rights.

Seen from the perspective of national populists, "the people" are a homogenous and unambiguous community that is contrasted with the neglectful, self-serving and corrupt elites. The "pure people" is based on a more exclusive and organic conception of the nation, which populists argue must ultimately be defended from an array of wider threats: immigration and rising ethnic diversity, Islam and growing Muslim communities, and social liberalism.

In more recent years, many national populists have also modified their position on the economy. During the 1980s and 1990s, many of these parties were broadly comfortable with free market capitalism, which was partly linked to their strong opposition to communism. But since then many have become more critical of capitalism and the role of the market. Today, many national populists have shifted more closely to an economically nationalist position. Marine Le Pen, Steve Bannon and others argue that free-market capitalism has been detrimental to the interests of workers and undermines the culture of the nation. It is often argued that national governments should now prioritize the rights and interests of the working-class over large-scale transnational corporations that have no real obligation to the national community.

Historical Trends

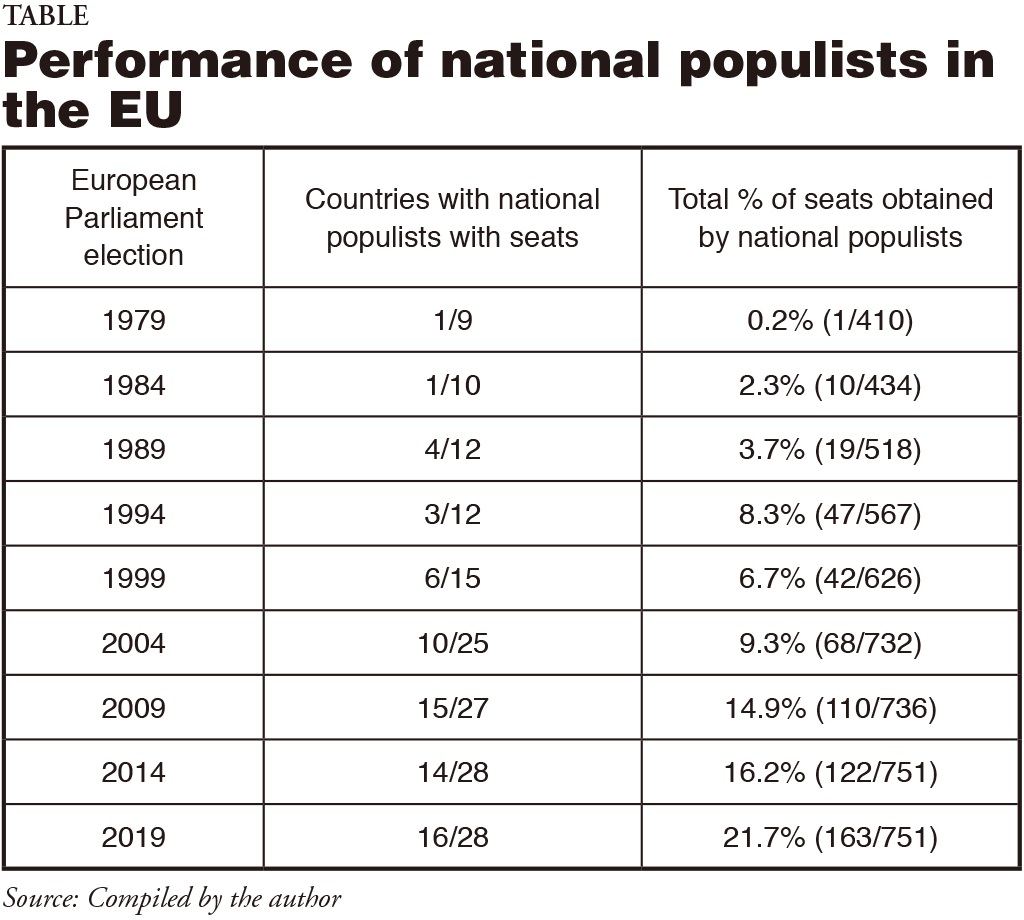

How has national populism performed over time? We can explore this question by considering, first, the historic trend in public support for these parties in Europe. For this paper, I have examined how dozens of national populist parties have performed in European Parliament elections, which have been held every five years since 1979. This is a useful way of examining the broader evolution of this party family. It also allows us to see how these parties have generally moved through three distinct periods: a period of breakthrough, a period of growth and then a period of consolidation.

In the first election, held in 1979, the only successful national populist was the right-wing Progress Party, which polled 5.8%. Overall, at this election these parties were barely visible – they won only one seat, or 0.2% of all seats in the European Parliament. But from hereon, throughout the 1980s, the number of successful parties began to grow. National populism entered its "breakthrough" stage.

Most analysts link this breakthrough period to several factors: to the end of the postwar economic "miracle", which saw strong rates of growth come to an end with the oil crisis and rising unemployment; to rising public concern over new waves of immigration into Europe; to the "modernization" of Western societies that included a weakening of trade unions and a more individualistic society; and to national populist parties themselves becoming more effective at campaigning. Specifically, they started to distance themselves from the open racism and opposition to liberal democracy that had marked their more unsuccessful predecessors. The breakthrough period saw parties like the French National Front, the Republicans in Germany, the Flemish Bloc in Belgium and the Danish People's Party poll strongly. By the end of the 1980s these parties held 19 seats in the European Parliament, or 3.7% of the overall total (Table).

During the 1990s and 2000s this period of breakthrough made way for a period of "growth", as many parties began to poll even stronger. Having held only 0.2% of seats in the European Parliament in 1979, the populist parties had achieved 8% by 1994 and would later gain nearly 15% in 2009, 16% in 2014 and then 22% in 2019. During the 1990s, they continued to benefit from public discontent with the established political parties, rising immigration and a strong sense of pessimism about the future. They were also helped by the end of the Cold War, which shifted the focus away from large external "systemic threats" in the global world order and back onto the nation-state. This helped the populist parties to turn up the volume on issues such as immigration and national identity – issues that mainstream politicians often avoided discussing.

Fast forward to the 2000s and 2010s and these parties had started to enter a phase of "consolidation". Several external events helped: the terrorist attacks on Sept. 11, 2001, the recession in 2008, and the emergence of a major refugee crisis in 2014. Against this backdrop many populist parties began to enjoy their strongest returns. By 2014, the number of countries where such parties polled at least 10% had jumped from 14 to 23, while the number of countries where they polled at least 20% grew to 12, with seven polling more than 30% of the vote. Countries with especially strong national populist parties included Hungary, Italy, Bulgaria, Poland, Greece and the United Kingdom.

Populist Party Supporters

Who was voting for the national populist parties? During the 2010s, many studies confirmed that much of this support came from less well educated, working-class and socially conservative voters who tended to share two motives: first, they wanted to express their opposition to, and distrust of, the main parties; and, second, they wanted to voice their concerns about the level and speed of immigration and rising ethnic and cultural diversity. Men, production workers, and those who had left school at the earliest opportunity were the most likely to cast a vote for these parties. There were some important exceptions. For example, at the 2017 presidential election in France, Marine Le Pen polled fairly strongly among young women and also LGBT voters who felt anxious about the growth of Islam and Muslim communities. In the UK, the Brexit Party drew much of its support from older voters, while in countries like Italy and Austria the populist parties were more successful among the middle-aged and young. But, in broad terms, these are parties that have relied most heavily on working-class men who feel left behind by globalization and anxious about immigration and ethnic change.

Continuing Consolidation

The consolidation of national populism had continued up until the most recent elections in 2019, leading many commentators to suggest that perhaps support for these parties had peaked. Once again, the most successful of these parties were in Hungary, France, Poland and the UK, although this time a number of other countries saw some very significant results. Italy saw the rise of Salvini's League, which had become successful enough to join a national coalition, before resigning from it in 2019. Several other parties in countries that had once been considered immune to national populism also broke through for the first time. In Spain, Vox became more visible, while in Sweden the Sweden Democrats also enjoyed a record result. Overall, national populist parties won at least 10% of the votes in no less than 16 countries, at least 20% in seven countries and at least 30% in four. They could now claim, in 2019, to have more than 16% of all seats in the European Parliament – a record high. Matteo Salvini, Marine Le Pen, Nigel Farage and Viktor Orbán have become household names.

The period of populist consolidation has also been reflected in other events. Similar movements have also polled strongly elsewhere in the world, including support for Trump in 2016 and for Bolsonaro in 2018. These examples point to how a growing number of populist parties have entered governments around the world. Indeed, recent analysis confirms that there are "nearly five times as many populist leaders and parties in power today than at the end of the Cold War, and three times more since the turn of the century" ("High Tide? Populism in Power, 1990-2020" by Jordan Kyle and Brett Meyer, Tony Blair Institute for Global Change, 2020).

Crucially, the influence of populist parties has also been indirect, with several studies showing how their electoral rise has encouraged mainstream parties to adopt tougher positions on issues such as immigration, law and order, and integration. This can be seen in countries like the UK, where the Conservative Party has adopted many of the policies that were previously advocated by the national populists, including its support for Brexit, a more restrictive migration policy and greater redistribution between the different regions. It also helps to explain why many center-left social democratic parties have struggled to retain support. Particularly since 2005, and mainly in Europe, social democracy has plummeted to record or near-record lows as voters have wanted to talk more about identity and belonging, and less about traditional economic questions.

National Populism at Peak?

To what extent, then, does this third phase of consolidation signal that national populism has now peaked? This question is likely to attract a great deal of attention should Trump lose the presidential election in 2020 and French President Emmanuel Macron win re-election in 2022. It is not hard to see how the global debate might swing quickly behind the assumption that it is now populism, rather than liberalism, that is in retreat. But putting these specific contests to one side, there are three factors that look set to influence the fortunes of national populism around the globe: (1) public demand for populism; (2) immigration; and (3) the more recent coronavirus crisis.

In terms of public demand, it seems unlikely that there will not remain an appetite for populist policies in the years to come. As recent surveys have underlined, there remains considerable disillusionment with the performance of national economies and strong distrust of established politicians. For example, according to a major survey of 27 states by Ipsos-MORI in 2019, globally 70% agreed that their economy is "rigged in favor of the rich and powerful", 66% agreed that "traditional parties and politicians don't care about people like you" and 54% agreed that their "society is broken", a figure that jumped to 63% in the UK and 84% in Poland (https://www.ipsos.com/ipsos-mori/en-uk/global-study-nativist-populist-broken-society-britain). The same survey found that 64% of adults agreed with the suggestion that their country "needs a strong leader to take it back from the rich and powerful", with the French (77%), Indians (72%) and Belgians (65%) being most likely to share this view. Linked closely to this demand is the specific issue of migration, which lies at the heart of the appeal of national populism. Eric Kaufmann has convincingly shown that as members of the ethnic majority in Western states become aware of their declining share in the overall population, they become more likely to backlash politically, voting for populist and ultra-conservative parties (Whiteshift: Populism, Immigration and the Future of White Majorities, Penguin, 2018). Immigration is also likely to remain highly salient in the years ahead as Republican voters in the US, Brexit voters in the UK and others across Europe call for lower levels of migration and more restrictive policies. For example, according to a major study by the Pew Research Center in 2019, more than 70% of voters in Greece and Hungary view immigration as a "burden", a view shared by 54% of Italians, 50% of Poles, 42% of the Dutch and 39% of the French (https://www.pewresearch.org/global/2019/03/14/around-the-world-more-say-immigrants-are-a-strength-than-a-burden/). The same survey found that between 2014 and 2018 public attitudes toward immigration had become more negative in Greece, Germany, Italy and Poland but more positive in Spain, the UK and France. Such numbers suggest it is unlikely that one of the core issues for populists will fade from the horizon. The European Union has also still not resolved the lingering refugee crisis in southern Europe while the outbreak of yet another economic crisis in 2020, coming little over a decade after the recession in 2008, will likely exacerbate these tensions further.

Possible Impact of the Covid-19 Crisis

This brings me to the third and final point about the future potential for national populism: the Covid-19 crisis. Before exploring this, it is important to note how the current crisis – the lockdown – differs from the previous crisis – the recession. The crisis of 2008 was a "double crisis" that was economic and political, whereas as the crisis of 2020 is a "triple crisis" that impacts health, the economy and politics. The crisis of 2008 was "top down", beginning in financial markets and then spreading across society, whereas the crisis of 2020 is "bottom up". Already, studies in the US and the UK confirm that it is the left-behind, economically precarious low-skilled and less well-educated workers who are most likely to die from the virus and also suffer the adverse economic effects that have followed the outbreak. In the UK, for example, it is those same production workers, builders and low-skilled retail workers who in the working age population have been most likely to experience disproportionately high death rates.

It is also worth noting that different social and economic groups will have fundamentally different experiences of this crisis. At the start of this crisis self-isolating was largely compulsory. But it is now becoming voluntary, with the professional middle-classes being more likely to be able to work from home. Over time, self-isolation will become an economic luxury and one that is largely restricted to those who have university degrees and professional occupations. This may exacerbate many of those social divides that had started to open before the recession of 2008 and were then sharpened by it. It seems unlikely that this crisis will promote cross-class solidarity.

Lastly, this crisis looks set to fundamentally and permanently reshape the public view of China. Already, around the globe an array of polls and surveys suggest that attitudes toward China are hardening. Before this crisis, when people tended to think about China they often associated the country mainly with trade and economic competition. But this crisis looks set to feed a much wider debate about whether or not China presents a "systemic threat" to Western values, human rights and, ultimately, ways of life.

For example, since the crisis erupted Americans have become far more convinced that China poses a "major threat" (62%), and are more likely to hold unfavorable views of China (66%) and express no confidence in President Xi Jinping (71%). Crucially, these views cross party lines. Disliking China is quickly becoming one of only a few things that unite a deeply polarized America. For example, the Pew Research Center recently revealed that 75% of Americans think their country should end its dependence on China for medical supplies. This issue will also have implications for the US presidential election in November. Some podcasts by Trump campaigners indicate they plan to turn the presidential race into a referendum on China, to shift the focus away from the domestic handling of the crisis onto this perceived threat. Democratic presidential candidate Joe Biden, who some Trump campaigners call "Beijing Biden", will be presented as being too soft on China.

Most Americans, and many others around the globe, have not had to think about systemic threats in this way since the end of the Cold War. Younger generations have largely not had to think about them at all. While attitudes toward China were already deteriorating before this crisis, an array of surveys since the outbreak of Covid-19 – in not just the US but also the UK, India and Australia – suggest they have deteriorated further. Sensationalist talk about "the end of globalization" is misleading – globalization will muddle on. But as we come out of this crisis, and most likely without an independent international investigation into how it started in the first place, there will be greater public pressure on governments to localize supply-side chains and take a tougher line on China. It is not hard to see how this new climate might benefit those who will seek to blame the crisis on a new external threat.

For each of these reasons, therefore, it feels unlikely that national populism is about to retreat. Over the past three decades, and especially in Europe, it has passed through the stages of breakthrough, growth and consolidation. By the time of the coronavirus crisis many of these parties had become established and serious players in their political systems. The outbreak of the crisis, like the one before it, looks set to exacerbate the underlying social divides that have helped to bring about this consolidation, and so while national populism has peaked, I find the suggestion that it will now decline somewhat unconvincing.

Japan SPOTLIGHT July/August 2020 Issue (Published on July 10, 2020)

(2020/08/12)

Matthew Goodwin

Matthew Goodwin is professor of Politics at Rutherford College, University of Kent, and associate fellow of the Royal Institute of International Affairs at Chatham House. He is the author of six books including the 2018 Sunday Times Bestseller, National Populism: The Revolt Against Liberal Democracy (Penguin).

Japan SPOTLIGHT

- Coffee Cultures of Japan & India

- 2025/01/27