HOME > Japan SPOTLIGHT > Article

2023 Will Be a Critical Year for the BOJ

By Nobuyasu Atago

Conceptual Definition of Price Stability

At the August 2022 Jackson Hole Economic Symposium, an economic policy symposium hosted by the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell made an extremely important point. Quoting former Fed Chairman Alan Greenspan from 1989, he once again explained the conceptual definition of the price stability that is the central bank's objective. Price stability, he said, "Means that expected changes in the average price level are small enough and gradual enough that they do not materially enter business and household financial decisions." This showed that he had a strong sense of crisis regarding the risk currently being faced.

The Bank of Japan (BOJ) has in fact expressed a conceptual definition of price stability many times in the past. Specifically, this was in October 2000 immediately after the zero interest rate policy was lifted, in March 2006 when quantitative easing was lifted, and in January 2013 when the 2% "price stability target" was implemented. Those explanations were consistent. The BOJ said that price stability is "A state where various economic agents including households and firms may make decisions regarding such economic activities as consumption and investments without being concerned about the fluctuations in the general price level." This is basically the same as the explanation given by Greenspan.

The reason this definition is important is that in both Japan and the United States price stability is stipulated by law as the central bank's objective. In other words, the ultimate objective of both the Fed's and the BOJ's monetary policy is price stability, not a 2% price target. The figure of 2% is nothing more than an intermediate target toward realizing the final objective. Therefore, being fixated on achieving 2% while losing sight of the final objective is putting the cart before the horse. Unfortunately, however, the central banks of both Japan and the US have fallen completely into this situation.

Fed Falling "Behind the Curve"

Since the summer of 2022, the US has been experiencing its highest inflation in 40 years. The effect of the coronavirus pandemic restricted supplies through both labor shortages and difficulty in parts procurement, and in addition there is no question that the more than $6 trillion in economic measures carried out by the Donald Trump and Joe Biden administrations had an effect as well. But that is not all. The US consumer price index (excluding food and energy) rose more than 3% year-on-year in April 2021, and despite the fact that the rate of increase rose above 4% from early 2022, the Fed did not begin raising interest rates until March 2022. At the time, Powell admitted at a press conference to having fallen behind the curve, noting that if they had been aware of the supply blockages and their effect on inflation they would have moved earlier.

How did the Fed fall behind the curve? In fact, it had been aiming to maintain a 2% price target, which it had not achieved for some time after the 2008 global financial crisis, and under the average price target strategy adopted in August 2020 the policy was left in place for some time even after the inflation rate surpassed 2%. This backfired. For the Fed, which fell behind the curve in raising interest rates and permitted high inflation, keeping inflation in check is its top priority, rather than overall economic conditions. Therefore, it has been raising rates since March 2022 at an unprecedented pace, despite the risk of falling into a recession.

Price Stability Has Also Collapsed in Japan

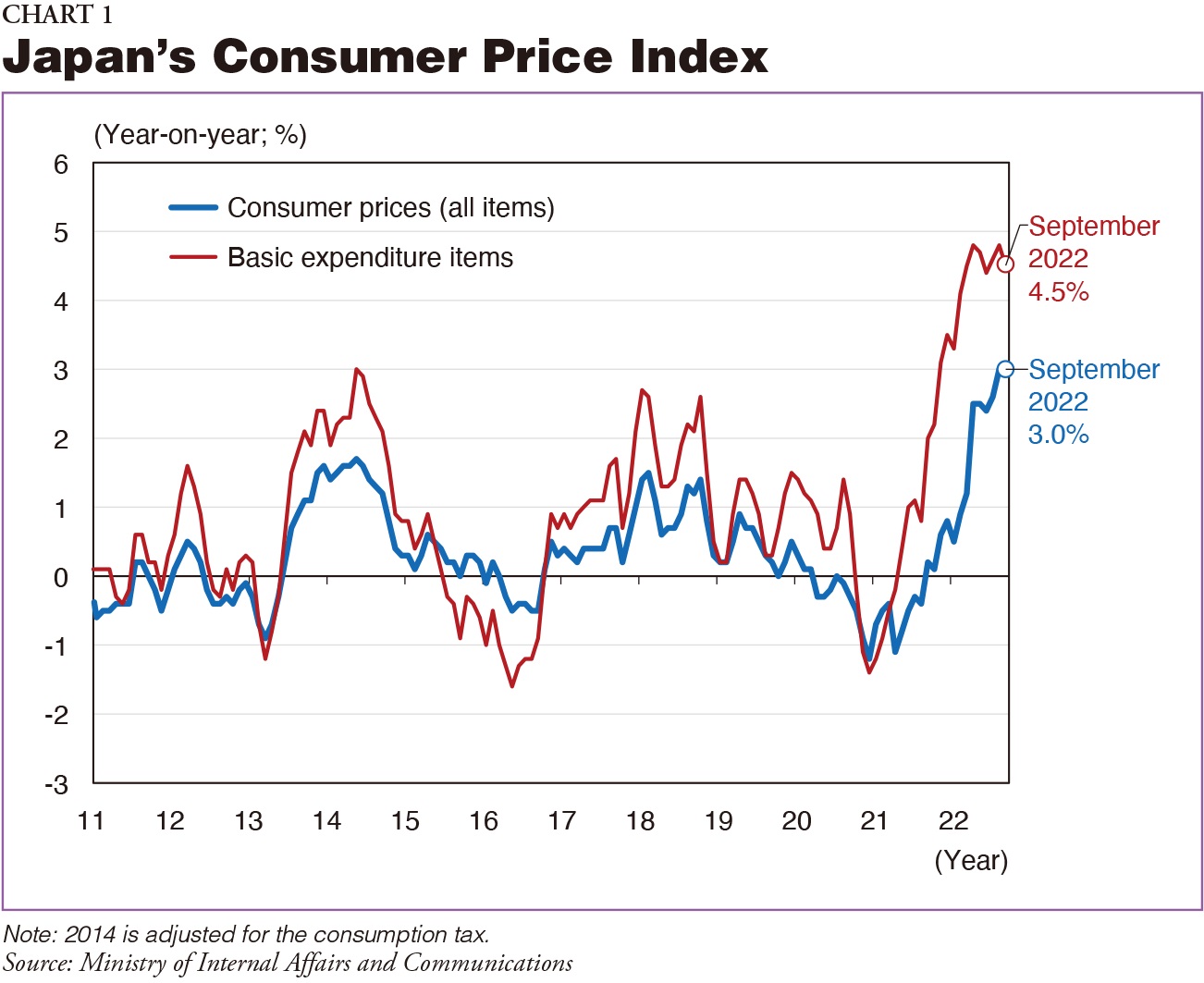

Price stability has collapsed in Japan as well (Chart 1). The rise in the consumer price index (CPI) hit the 3% year-on-year level in August 2022. Excluding the consumption tax effect, this was the highest increase in 31 years – since August 1991. The level for October is likely to have risen to the mid-3% range. With wage increases remaining sluggish, continued inflation above 3% could inflict significant damage on consumption in Japan. Chart 1 shows the CPI for basic expenditure items derived by reclassifying the CPI components. This index, which includes many daily necessities for which prices are less affected by demand, shows the rate of increase to be in the mid-4% range year on year, meaning inflation as actually being felt by people is much higher than 3%.

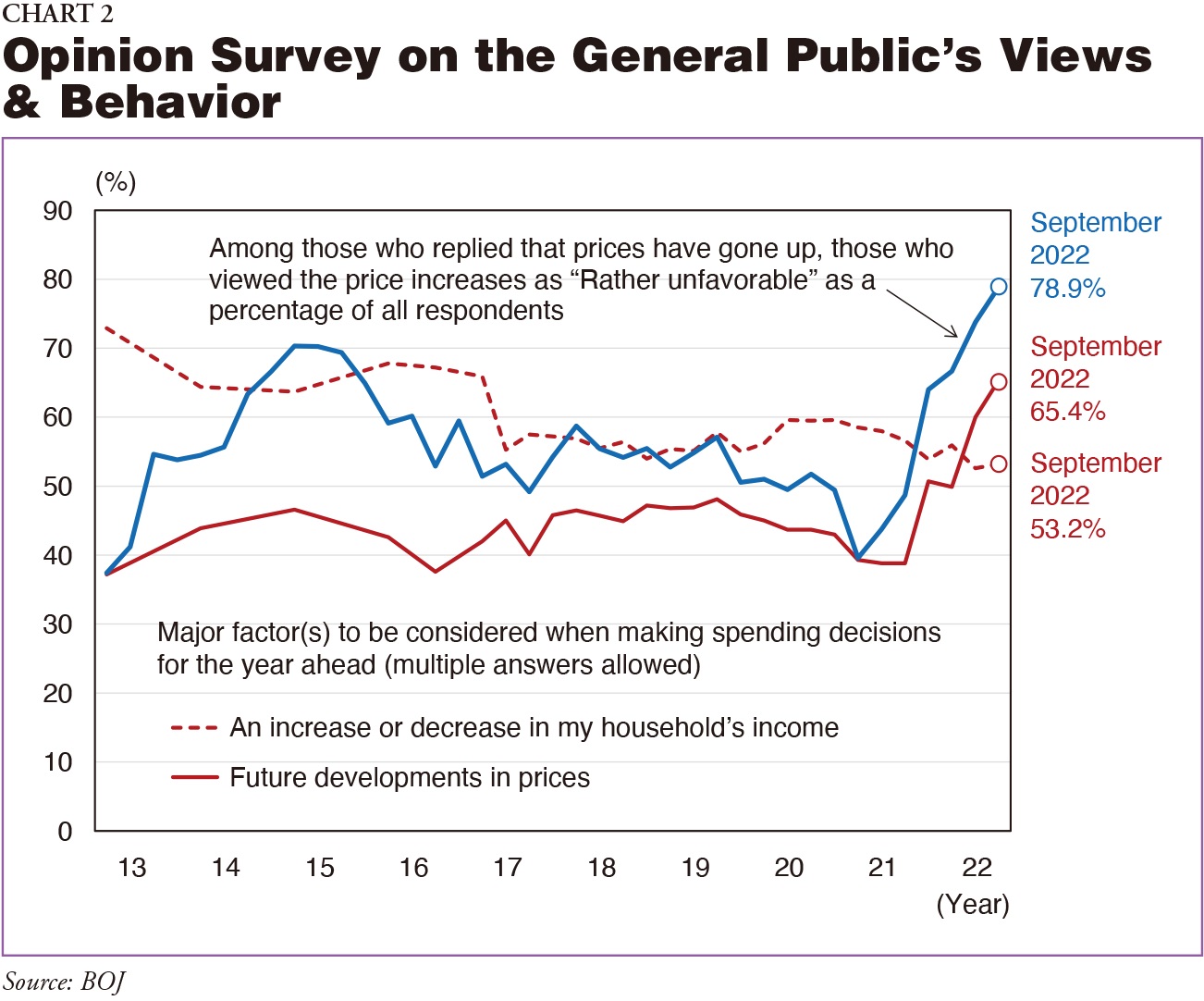

Many Japanese people are already feeling the burden of current inflation. Chart 2 shows the results of the BOJ's Opinion Survey on the General Public's Views and Behavior. The blue line shows the percentage of people, among those who replied compared with one year ago, who think prices "Have gone up significantly" or "Have gone up slightly" and who viewed price increases as "Rather unfavorable", and this figure has recently increased significantly. The red line and the dotted line show the "Future developments in prices" and "An increase or decrease in my household's income", which are particularly major factors to be considered when making spending decisions. "Future developments in prices" has overtaken "An increase or decrease in my household's income" since the June 2022 survey. In terms of the aforementioned conceptual definition of price stability, the Japanese people are clearly disturbed by price level movements.

Unmoving BOJ

Nevertheless, the BOJ has shown absolutely no signs of moving (at least as of the writing of this article in late October). If anything, BOJ Governor Haruhiko Kuroda's explanation has been that recent inflation is a temporary result of supply constraints, and that it is important to be tenacious in maintaining easing. This assertion closely resembles Powell's in 2021 when the Fed fell behind the curve, but Kuroda appears to believe that wages will not rise sufficiently unless Japan emerges from low growth, and seems confident that against that backdrop current inflation will not continue for an extended period. In addition, the US and European countries are beginning to move toward normalization even as the risk of falling into recession is increasing, but in the event Japan was to do the same and that caused an economic downturn, there is no question that Kuroda would bear the brunt of the criticism.

The important point is a secondary ripple from an upturn in wage increases and inflation expectations. At the aforementioned Jackson Hole symposium, Powell affirmed that whether inflation is caused by increased demand or supply constraints, this does not reduce the Fed's responsibility for price stability. Underlying this statement is a caution against a secondary ripple from an upturn in wage increases and inflation expectations. If this were to occur, the inflation that the Japanese people are already struggling with would be increasingly prolonged.

On the other hand, Kuroda expects a secondary ripple. His best-case scenario is that as the coronavirus pandemic is eventually brought under control, the economy will normalize and this will bring about an improvement in corporate earnings, which in turn will lead to a recovery in the balance between wages and higher inflation rates. It would be ideal if the 2% price stability target were then achieved, but that would be a miracle. Kuroda's thinking that a certain degree of wage increases would eventually lead to inflation falling below 2% is realistic. And the risk of recession in the US and Europe is increasing. There is currently no rational reason for Kuroda to move toward normalization, and people are being forced to endure high inflation while seeing the BOJ's inaction.

Diminishing Market Function

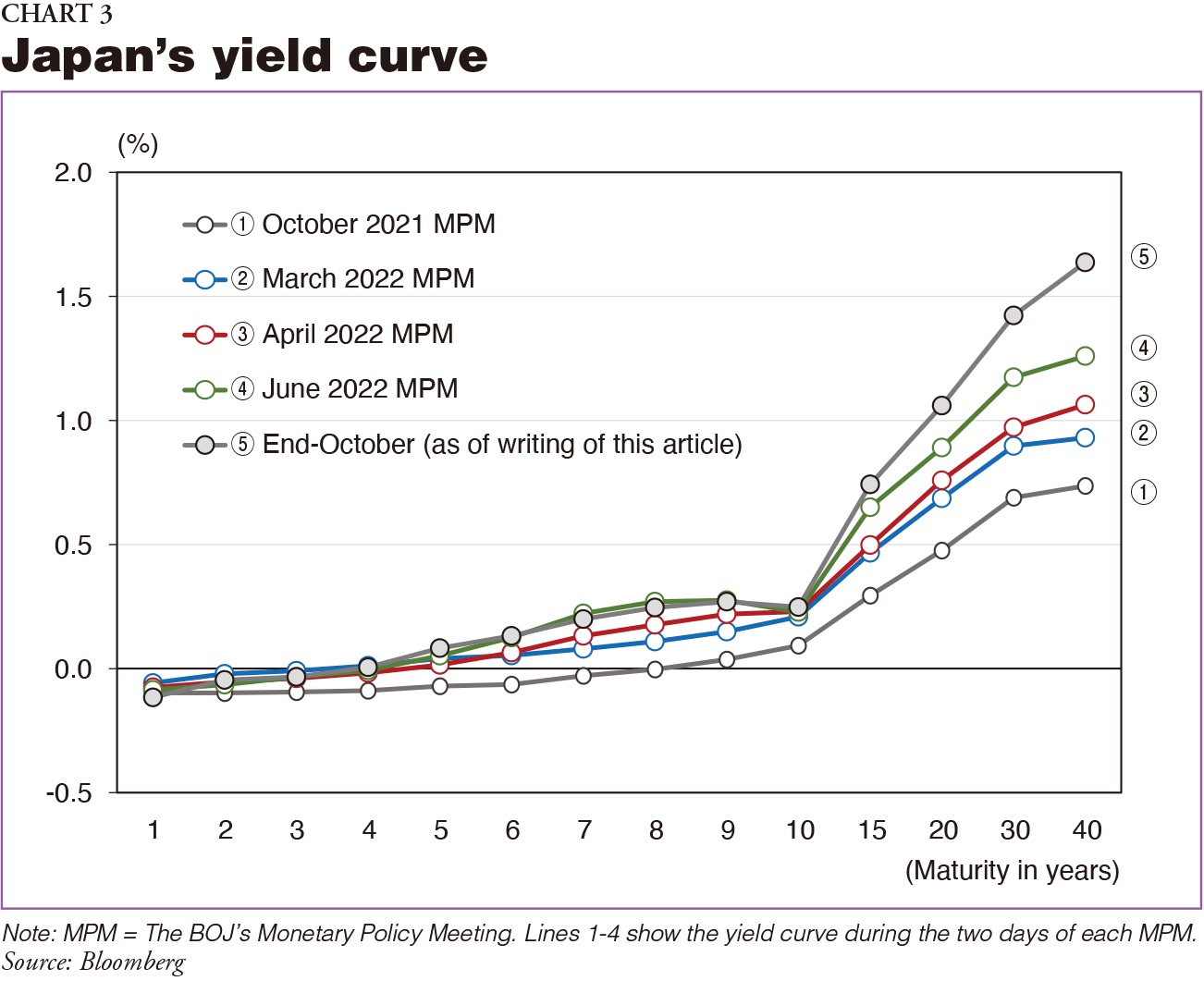

Market distortions are also increasing significantly as a result of Kuroda's stubborn refusal to act. Currently, the BOJ's yield curve control (YCC: officially "Quantitative and Qualitative Monetary Easing with Yield Curve Control") means that a negative 0.1% interest rate is being applied to a portion of financial institutions' current account deposits at the BOJ, while at the same time the guidance target for 10-year rates is "approximately zero". If the BOJ were to be strict in controlling the 10-year yield at 0%, however, the side effect of less liquidity for Japanese government bonds (JGBs) would increase, so the BOJ is tolerating 10-year yield fluctuations within a band of -0.25% to +0.25%.

Against this backdrop, US long-term interest rates, factoring in Fed rate increases, began rising sharply from March 2022, and this led to a stronger trend of Japanese 10-year yields rising as well. As a result, the upper level of 0.25% was exceeded in late March, and the BOJ was forced to use "fixed-rate purchase operations for consecutive days", in which it purchased an unlimited amount of JGBs at a designated rate to bring the yield below 0.25%. In addition, it is not only 10-year yields that rise along with US long-term interest rates. This put upward pressure on the entire yield curve, from short- and medium-term maturities to ultra-long-term maturities. Despite this, the BOJ continues to force only the 10-year yield lower, and as a result major distortions have emerged in the Japanese yield curve (Chart 3).

In mid-June, 7- to 9-year yields rose above 10-year yields, so the BOJ added 7-year JGBs, which are deliverable issues for futures (cheapest issues) to the scope of its fixed-rate purchase operations for consecutive days. This, however, invited greater market distortion and disruption. With liquidity for newly issued 10-year JGBs having become extremely low, there was then a huge drop in liquidity for 7-year JGBs, making it difficult to procure cash bonds for arbitrage transactions with futures. As a result, JGBs needed to settle futures transactions could not be procured, and many deliveries failed (settlement was not completed). In addition, because of the large divergence between futures prices and cash prices, futures' hedging function diminished. It became particularly difficult to use futures to hedge ultra-long-term cash JGBs, and this had an adverse effect on bidding and transactions for ultra-long-term JGBs. This distortion in the yield curve continues today, making the bond market quite vulnerable as yields in ultra-long maturities are easily prone to rise.

Continuing Yen Weakness

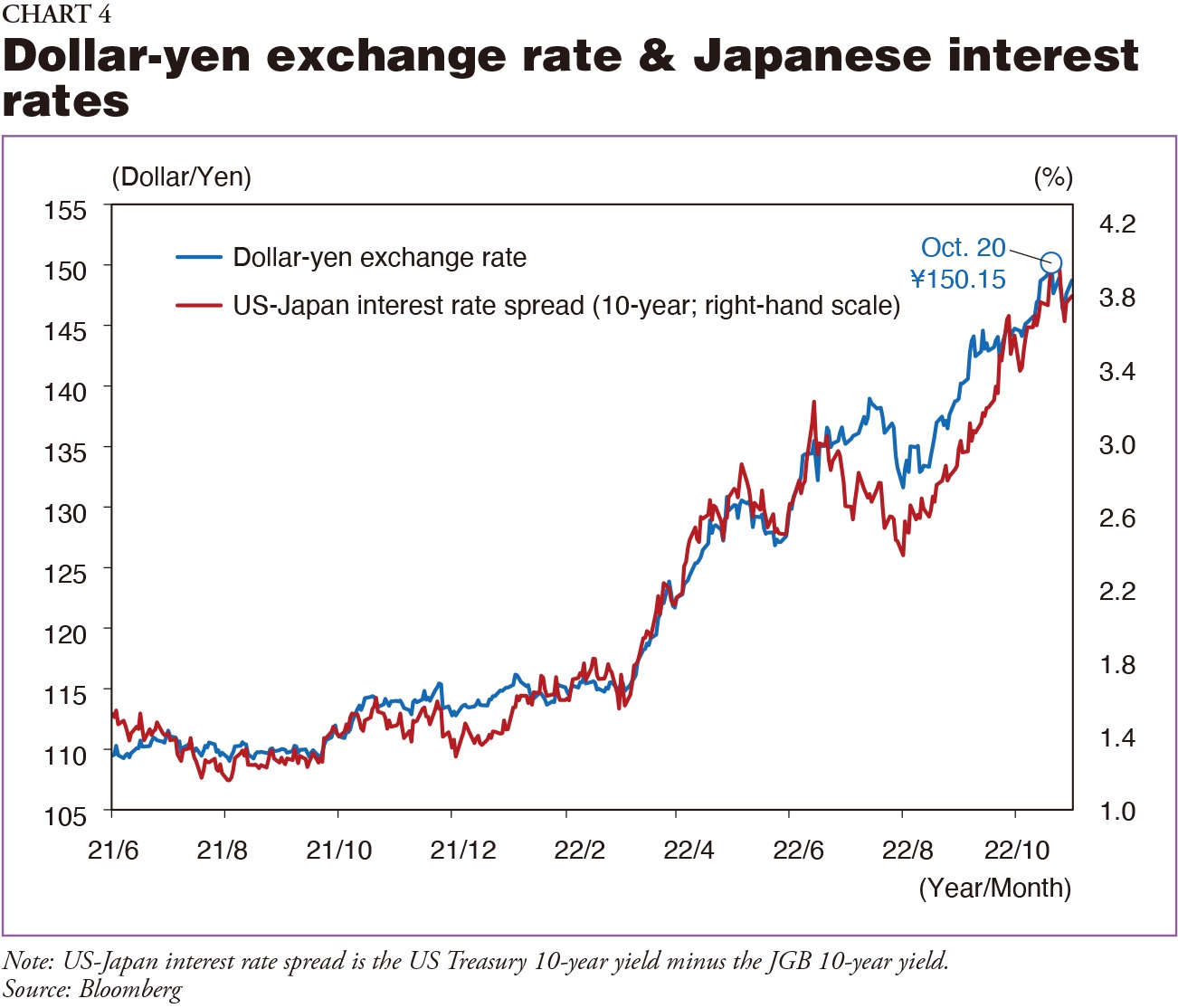

While long-term interest rates in the US are rising sharply as they factor in inflation and rate hikes, long-term rates in Japan are being held to 0.25% through the BOJ's rigid YCC, causing a rapid widening of the spread between US and Japanese rates. This encourages the buying of dollars for yen, and the dollar-yen market, which had been stable at the \110 level until February 2022, saw the yen weaken by 40% from March to August (Chart 4). The Ministry of Finance, which has jurisdiction over currency policy, began intervening by buying yen and selling dollars when the yen fell to \145.90/$ on Sept. 22, its weakest level since August 1998. This did not halt the yen's slide, however, and the BOJ intervened for a second time on Oct. 21, immediately after the yen fell below the psychological benchmark of \150/$.

With these recent exchange rate movements, and amid the jostling among countries to prevent their currencies from weakening and thereby feeding inflation, Kuroda's repeated comments tolerating the yen's weakness appear to have held back the Japanese government. As with other central banks, however, the BOJ does not make policy adjustments to account for exchange rates, and it should not. If exchange rates do affect monetary policy management, it would be in cases, for example, where they are combined with a spike in resource prices and having an adverse effect on the Japanese economy. Accordingly, the important thing to consider when considering the direction of monetary policy is not to look for the future direction of exchange rates, but rather to analyze the effect of current exchange rate movements on the economy and prices.

Deflationary Pressure from Deteriorating Terms of Trade

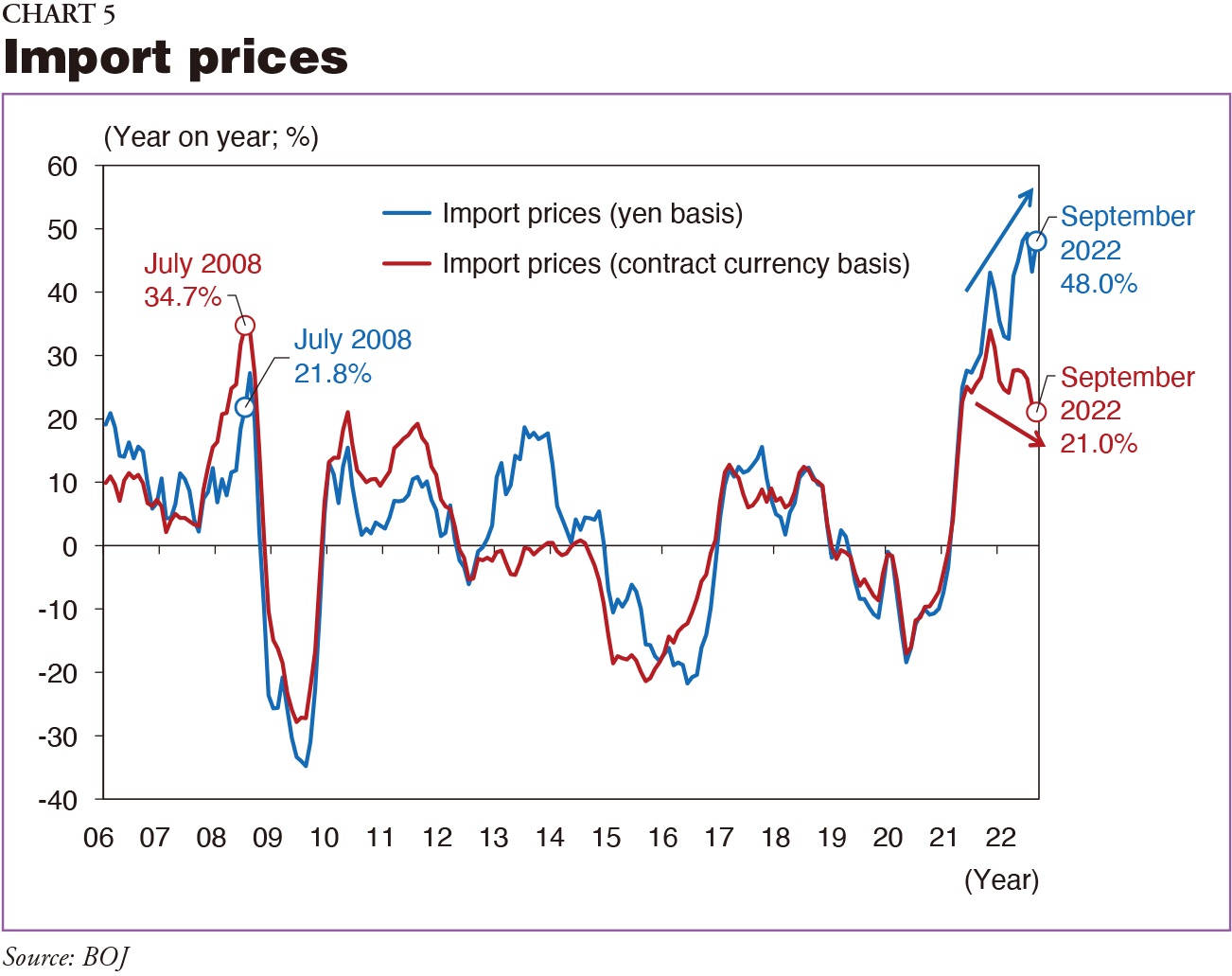

Drastic yen depreciation like we are seeing today significantly raises import prices in yen terms, and higher costs for imports puts upward pressure on domestic prices. Import prices compiled by the BOJ are on a contract currency basis and a yen basis. The contract currency basis indexes import prices in the currency in which the importer actually concluded the import contract, and the yen basis indexes contract prices in yen terms. We are now beginning to see a drop in resource prices that had risen sharply as a result of developments including Russia's invasion of Ukraine, and the year-on-year increase in import prices on a contract currency basis is narrowing. With the yen's drastic depreciation, however, the year-on-year increase in import prices on a yen basis continues to grow (Chart 5).

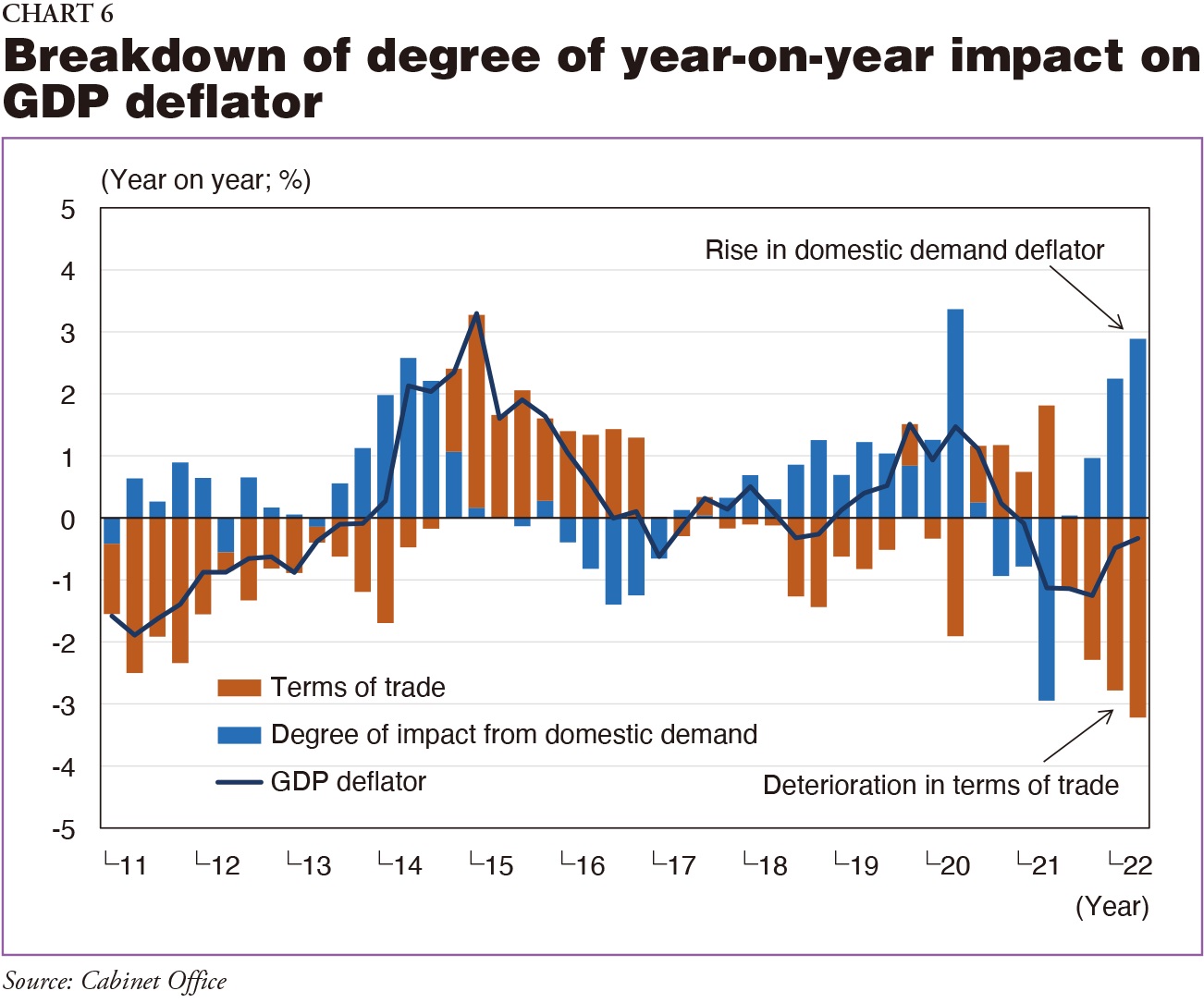

The rise in import prices (yen basis) not only causes inflation by pushing up domestic prices, it also puts deflationary pressure on the economy by curtailing corporate earnings and retail consumption. This rise in import prices, which has both inflationary and deflationary aspects, creates a peculiar phenomenon in which the GDP deflator falls even though consumer prices and the domestic demand deflator are rising. For the April-June 2022 quarter, consumer prices (all items) rose 2.4% and the domestic demand deflator was 2.6%, but the GDP deflator was a negative 0.3%. These twists and turns are created by terms of trade.

Real GDP is a country's nominal GDP – the total of the country's added value – excluding the effect of price fluctuations, and the GDP deflator shows those price fluctuations. Broadly speaking, because GDP is made up of both domestic demand and external demand (exports minus imports), the GDP deflator can be expressed as three variables: the domestic demand deflator; the external demand-related deflator, in other words the export deflator; and the import deflator. The import and export deflators are used to compile import and export prices. If we understand the difference between the export deflator and the import deflator to be the change in terms of trade, it becomes possible to break down the degree to which the GDP deflator is affected by the domestic demand deflator and terms of trade. This calculation is shown in Chart 6.

Looking at this chart, the effect from the domestic demand deflator has recently been rising significantly, while at the same time terms of trade have deteriorated by an even wider margin, for an overall negative effect, and this can be confirmed by the fact that the GDP deflator is negative year on year. It is the deterioration in terms of trade that creates deflationary pressure when the import deflator rises sharply, and this is the reason Japan's GDP deflator is not rising. This will come as a shock to adherents of the quantitative theory of money. From the January-March 2020 quarter to the April-June 2022 quarter, prior to the spread of the coronavirus pandemic, money stock (M2), formerly called the money supply, was growing significantly – by 35.1% in the US, by 17.9% in the euro zone, and by 14.3% in Japan – but on the other hand, while the GDP deflator rose to 11.9% in the US and 6.3% in the euro zone, it fell to a negative 1.0% for Japan.

Outlook for Monetary Policy

From this, we can say that in Japan we should not look at the GDP deflator for domestic inflationary pressure. The CPI is higher year on year at the 3% level, and the consumption deflator is also above 2%. In Japan as well – putting aside whether or not it is a temporary phenomenon – the unbearable inflation that people are facing is a fact, and this is why the BOJ is coming under increasing criticism for strictly sticking to the "price stability target" of continuously achieving a 2% rise in consumer prices and stubbornly continuing its unprecedented easing.

Maintaining low interest rates is the government's endorsement of populism, but we must not forget the major side-effect of complacency about the dangers of budget deficits. Discussions about the size of the second supplementary budget (general budget), passed by the cabinet on Oct. 28 as part of the comprehensive economic measures to overcome high prices and achieve economic revitalization, started at roughly \20.0 trillion to cover the GDP gap, but grew on requests by ruling party lawmakers who were concerned about the government's declining approval rating, and ended up at \29.1 trillion. Despite this uncontrolled fiscal expansionism, the fact that long-term interest rates did not react like they did in the United Kingdom is because the BOJ's YCC prevented that from happening. No matter how much the BOJ itself denies this, the market sees through YCC as blatant fiscal financing. Japan's fiscal situation is much more severe than the UK's.

The BOJ governor will be replaced this spring. This change can be seen as a critical moment for the bank's monetary policy. Markets are looking with anticipation toward monetary policy management after the retirement of Kuroda, who stubbornly refused to move toward normalization. This is true at least for JGB market participants and financial institutions. If the market becomes the price-making mechanism for 10-year yields, it will become clear that the restoration of the bond market, with a yield curve that conforms to fundamentals and the underlying assumption of arbitrage trading being carried out freely, is desirable.

The BOJ has two options. One is to continue with unprecedented easing while putting forth policies needed to address its side-effects. The other is to examine its policy, including a review of the position of its "price stability target" of a 2% rise in consumer prices, and to begin normalization. I see the most likely scenario being one in which unprecedented easing continues while addressing the side-effects as long as there is a high risk of a recession in the US and Europe, and after that recession ends and an upturn in the economic environment is confirmed, to embark on a policy review. The outcomes of the US and European economies and their monetary policy management will have a major effect on the BOJ's actions during 2023.

Note: This article was completed on Nov. 7, 2022.

Japan SPOTLIGHT January/February 2023 Issue (Published on January 10, 2023)

(2023/01/16)

Nobuyasu Atago

Nobuyasu Atago is senior operating officer and chief economist at Ichiyoshi Securities Co., Ltd. He worked at the Bank of Japan until 2015. He was also a chief forecaster at the Japan Center for Economic Research and a chief economist at Okasan Securities. He holds a Master's degree from Kobe University.

Japan SPOTLIGHT

- Coffee Cultures of Japan & India

- 2025/01/27