HOME > Japan SPOTLIGHT > Article

Okinawa, Land of the Happy Immortals: Interview with Prof. Gordon Maxwell

By Jillian Yorke

Okinawa: Hints for Long Life & Good Health

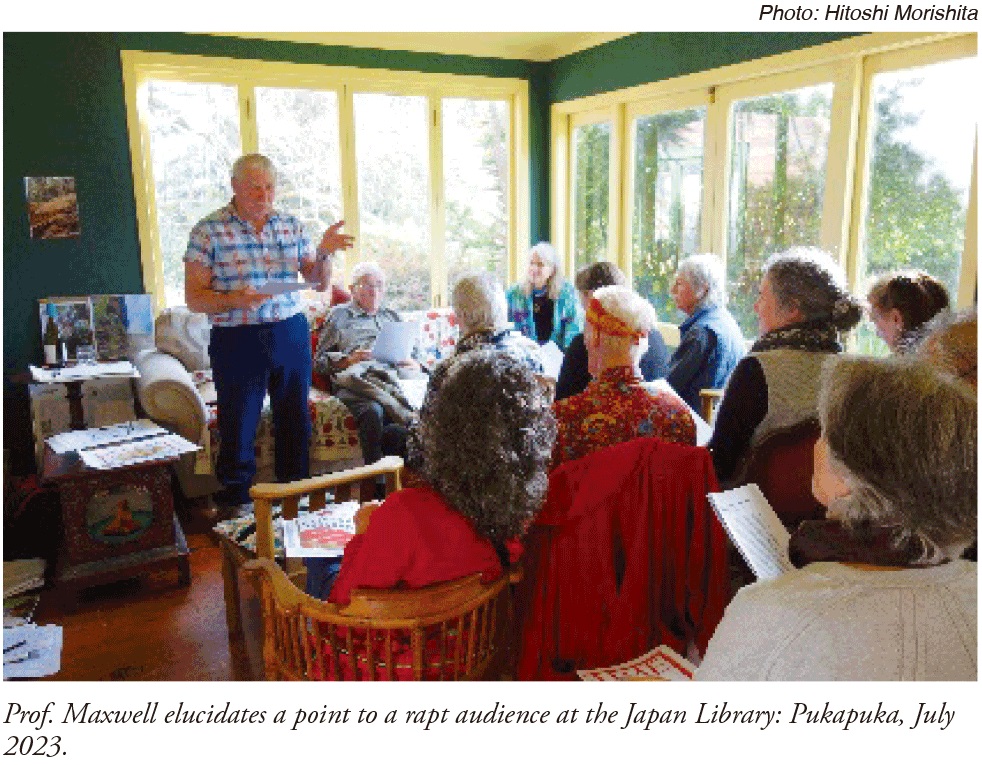

Okinawa, with its pleasant climate, unique history and culture, abundant and diverse fauna and flora, and laid-back lifestyle, has long been an appealing location for many people. On July 6, 2023, Professor Gordon S. Maxwell gave a fascinating talk at the Japan Library Pukapuka in Karanagahake, New Zealand, on his first-hand experiences and impressions gained while serving as the sole non-Japanese visiting professor attached to the University of Ryukyus at its most remote outpost. He discussed attitudes, philosophy, lifestyle, diet and dialect in Okinawan village life and the Okinawan archipelago, also known as "the land of happy immortals". The event was well attended; the audience eagerly lapped up the speaker's eloquent, passionate presentation, vast knowledge, and well-prepared materials and useful handouts, reflecting the universal interest in longevity and healthier living.

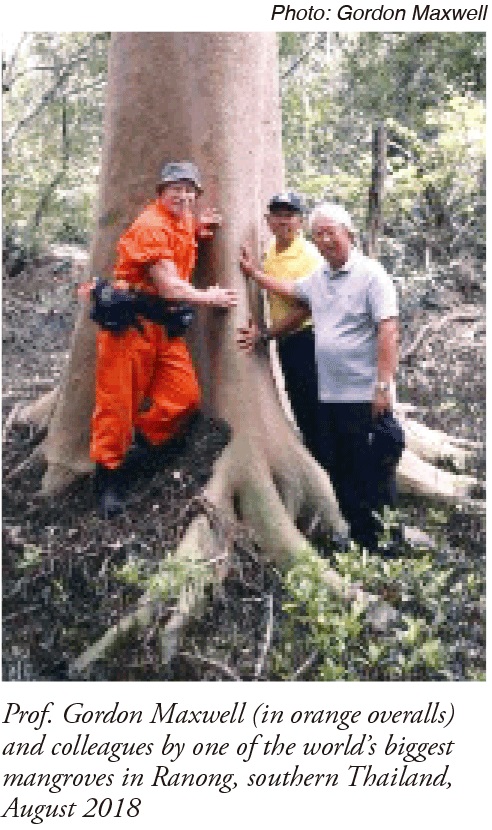

Prof. Maxwell, MA, MSc, PhD, Fellow of the Royal Society of Biology, is an ecologist and conservationist, with particular expertise in tree protection and mangrove studies. He has been a member of field-based research teams with the United States Antarctic Program and UNESCO. Although technically retired, he continues to lead fieldwork and conservation projects, splitting his time between his home in Hong Kong and his farm in Hikutaia, New Zealand. From his lifelong interest in biology, Prof. Maxwell believes that biology can enhance people's lives by deepening their connections with and understanding of the living systems that maintain the air, water and the environment.

In a follow-up to the Japan Library talk, I conducted an online interview with the professor.

JY: Please tell us something about your background and your connection with Okinawa.

GM: Mangrove research, which began in the late 1960s in New Zealand, brought me into contact with Prof. Sanit Aksornkoae of Thailand in 1980. From this meeting at Kasetsart University in Bangkok, the mangrove connections grew to include Dr. Sonjai Havanond of the Royal Forestry Department in Thailand and Prof. Shigeyuki Baba of Ryukyus University, Okinawa. The International Society of Mangrove Ecosystems (ISME) founded by Prof. Baba became a sustaining and enhancing catalyst for mangrove science, with a network which embraced the Tokyo University of Agriculture and the Mangrove Forest Research Center in the Ranong Province of Thailand.

I believe that there was something special about the Okinawan way of life that inspired Prof. Baba to nurture the ISME. He set up an electronic journal dedicated to mangrove science and the activities of ISME, and facilitated research and education expeditions to Okinawa (main island), Ishigaki and the very special Iriomote island in the Okinawa archipelago. In 2006, I was a visiting professor and researcher at the University of the Ryukyus' remote outpost on Iriomote. This was my second visit, the first being with the late Prof. Takehisa Nakamura of Tokyo University of Agriculture (TUA) back in the late 1990s, where we (Prof. Nakamura, Dr. Reiko Minagawa, Dr. Sonjai Havanond, and I--two Japanese, one Thai and one Kiwi) researched the mangrove mud lobster's strange mound-building behavior. Sonjai was then doing his PhD (TUA) studies under Prof. Nakamura and I was helping with field work. On both occasions I could feel something very positive and close to the essence of what generates and sustains health and happiness.

Typhoons & Cat Women

JY: What were your overall impressions and observations of the Okinawan lifestyle?

GM: You ask a very penetrating and good question when you inquire about how my Okinawan face-to-face experiences and observations had a big impression on me. During the TUA mud lobster field work, we stayed at a home on Iriomote known to Prof. Nakamura. Here the atmosphere was calm and the couple who owned the house had a serenity and calmness of persona which was, somehow, in phase with the peacefulness of the surroundings. Fresh seaweed and vegetables featured in the meals and a feeling of connection and happiness came with the food. At least part of this feeling was linked to nature and how the hosts had obtained both seaweed and vegetables from their island.

Several years later, in 2006, I visited a remote village in Iriomote and some old ladies did a folk dance and sang a song that included some traditional Okinawan dialect. An elderly lady gently beckoned me to dance, or more correctly and descriptively, to enable her to deepen the message she was attempting to share with me. An exchange of acceptance and understanding took place through eye-to-eye contact and a smile. Later, I returned to my research and rather monastic-like existence in the university outpost. Before leaving Iriomote and my research on mangrove forest structure, I experienced a typhoon and an encounter with two "cat women". The typhoon demonstrated the importance of mangroves as natural protective resources for fisherfolk and their boats. I was so impressed with the disciplined and calm appreciation of all this that I described it in a paper published by Coastal News in New Zealand (November 2006), entitled "In Winds of Hell...Escape to the Mangroves". In this paper, I outlined how Japanese people see the eco-economic value of mangroves and use them as a coastal refuge for their boats and themselves, as well as viewing them as ecosystems which sustain fisheries and provide natural products.

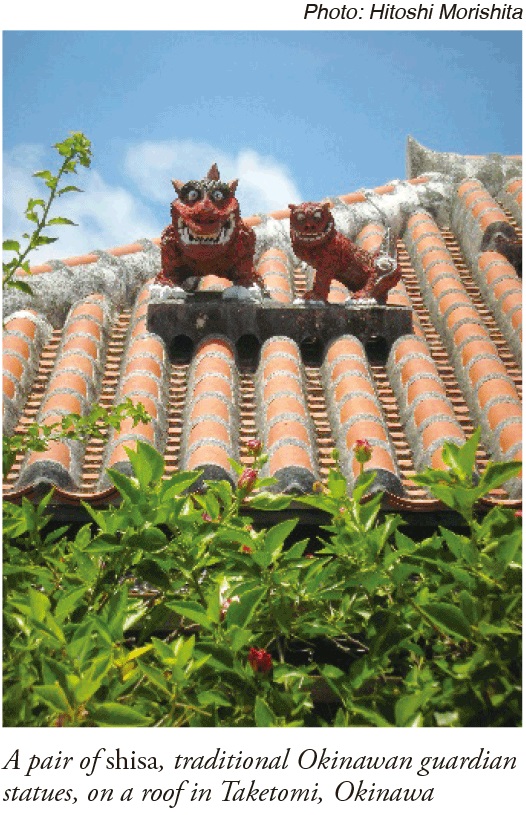

The cat women had studied the elusive and novel Iriomote cat, Felis iriomotensis, and had a deep affection and respect for this unique but endangered species, as indeed Okinawans in general do, as evidenced by the frequent road signs reminding people to keep alert, watch out for this precious cat, and protect its genetic diversity. Again, I detected that something much greater than pure science was in evidence here: it was a very Okinawan attitude to living in harmony with nature.

Wait Till You're 100!

JY: How did your attraction to and interest in Okinawa affect your later work?

GM: You ask me about how my embrace of Okinawa and aspects of its traditional culture has influenced my research and teaching. This is a very good question. There are many aspects to touch on here. I had shared some of my feelings and observations with a member of the ISME staff at Ryukyus University, Dr. Mami Kainuma, and she directed me to what has become a very important and much-loved book about attributes contained within the traditional Okinawan culture and lifestyle. This is The Okinawa Program by Bradley J. Willcox, D. Craig Willcox and Makoto Suzuki (2000, with a foreword by Dr. Andrew Weil, a renowned author on health issues). The book begins by quoting an inspiring Okinawan proverb: "At seventy you are but a child, at eighty you are merely a youth, and at ninety, if the ancestors invite you into heaven, ask them to wait until you are one hundred... and then you might consider it."

One aspect of my story here relates to the concept of human feeling. In The Okinawa Program, which was a bestseller, the authors describe this as omoro, which translated into English means "feeling" or "thought", omoro being a poetically expressed feeling or thought with many positive outcomes all related to mental and physical health and happiness. (Omoro originally referred to an ancient type of message-transmitting song.) I had experienced these feelings before I had read about them in The Okinawa Program. To discuss this fully would be way, way beyond the scope of this article. The essence of the message in The Okinawa Program is the theme that human health and happiness have their formation in a lifestyle which combines helping others, eating natural food, exercise, laughter, being easy-going, avoiding time-urgency stimuli, and being active at all ages. Of great interest to me has been that the Okinawan dialect does not have a word for retirement.

A host of thoughts, debates, arguments, and discussions could be triggered by an analysis of the consequences and implications of "retirement", such as: Was retirement invented to please those who control production? Did the pioneers of 19th-century New Zealand entertain a concept of retirement? Did Maori tribes retire older members of their community or did their functions in the community just ease up and change? How appropriate is a simple age-based retirement today? Is work a state of mind, just as an eight-kilometer walk to school is a hardship to a suburban child in a modern city, but part of normal life to a youngster in rural Nepal?

The Okinawa dialect does have the phrase hara hachi bu (the 80%-full rule for eating) and an easy-going or calm attitude captured in the Okinawan word taygay. Perhaps somewhat strangely and unexpectedly, my experiences and background seemed to connect with these Okinawa times and ideas. The lifestyles and outlooks of my mother and grandmother which were given to me (including a version of the idea of stopping eating a little before you feel full) were rekindled by components of my experiences in Okinawa, a very unexpected outcome.

A key underlying question was what is more important in long life: genes or lifestyle? Without a doubt, this book points strongly to lifestyle--although genetics does also count, to some extent.

Another special feature of Okinawa that amazed me was that even taxi drivers can talk about mangroves and appreciate their importance in ecology and sustainable fishing. Incidentally, all three authors of The Okinawa Program are still working, though Dr. Suzuki is now 89.

Seaweed for Longevity

JY: As you know, Okinawa is one of the world's five "blue zones", areas renowned for the exceptional longevity and sound health of their residents. I understand that your experiences in Okinawa inspired you to further study the field of longevity and healthier lifestyles. (Note: The other blue zones are: Sardinia, Italy; Nicoya, Costa Rica; Ikaria, Greece; and Loma Linda, California, USA.) What are the elements of a longevity-promoting diet?

GM: There is evidence that in the 24 years since The Okinawa Program was published, the health of Okinawans has declined somewhat from the earlier outstanding statistic of having the world's longest-lived and healthiest people. Lifestyle changes towards modern eating habits like fast food have contaminated the Okinawan food pyramid. This traditional food pyramid ensured that fruit, vegetables, tea and onions featured strongly alongside flavonoid foods like soy products, such as miso and tofu, and seaweeds. A meal with a Ryukyu University colleague which featured red, green and brown seaweed soups was a memorable experience for me and I felt sharper and very alert during the day which followed this dietary discovery.

My Japanese friend was pleased and impressed that I, too, was an algae lover. He was intrigued when I mentioned one of my childhood jobs, which involved trundling a home-made cart all the way to my local seaside and filling it with brown seaweed, lugging this home, chopping the seaweed up with a sharp spade, and placing this organic fertilizer into garden soil under the watchful eye of my mother. Brown seaweed, as it turns out, contains fucoxanthin, an antioxidant. The soup experience demonstrated that aspects of the traditional Okinawan diet are still strong, and can help younger Japanese people to rediscover what has made the Okinawan way world-famous.

The traditional Okinawan diet is low-calorie (about 20% lower than the Japanese average, which in turn is about 20% lower than the US average) and focuses on unrefined complex carbohydrates (such as fruit, vegetables, and fiber-full whole grains), treating food as a source of healing power (known as nuchi-gusui, or "food is medicine", in Okinawan). As a result of this healthful diet and their very active lifestyles, Okinawans experienced the world's lowest incidence of coronary heart disease, stroke and cancer (three of the main killers in the West).

Reconnecting with Tradition

JY: Unfortunately, the recent statistics for Okinawa (such as on lifespan, healthy lifespan, disease, well-being, and poverty) are disappointing, with the elders living longer but the young dying younger. How can Okinawans reconnect with their healthier and more beneficial original lifestyles?

GM: The intrusive, dehumanizing impacts of excessive use of mobile phones, iPads and Whats-Apping have formed barriers to many face-to-face, eye-to-eye and voice-to-voice components of village life. Addictive iPad electronic games are stealing human interaction time from teenagers and other age groups; talking to and interacting with other people, especially the older generation, is deflected. The age of IT may be a mix of good and bad if it distracts people from such a meaningful, traditional lifestyle.

Modern, Western increases in mental and physical health issues have highlighted the wisdom of the traditional Okinawan way. Dressed in medical jargon, we find health professionals talking about such mind-body matters as the advantages of hypometabolic wakefulness. Translated, this means learning how to relax and meditate using such activities as focused breathing, concentration on sound in gentle and pleasing music, refiguring emotions with an inner smile, walking gracefully, and undertaking tai chi. In a state of hypometabolic wakefulness, one relaxes, stays on the edge of sleep, and slows one's metabolism down (the prefix hypo here captures the idea of reduction, the opposite of hyper.)

Perhaps the lasting message that the traditional Okinawan lifestyle brings is that these approaches to life are as important today, in the third decade of the 21st century, as they ever were. During the research conducted as part of the basis for The Okinawa Program, it was discovered that Okinawan elders (aged 80 to 90-plus) had lower levels of free radicals in their blood compared to younger Okinawans. This was linked to their low-calorie intake and high antioxidant intake from vegetables and legumes such as soy beans. Their diet was about 80% plant-based. The core message here is that free radicals (of which lipid peroxide is an important example) are bad news because they damage our cells and cause aging.

The top 15 "Okinawan healing foods" mentioned in The Okinawa Program are, in order: Okinawan tofu, miso, dried bonito, carrots and carrot tops, sanpin (a type of jasmine) tea, goya (bitter melon), kombu (dried kelp), cabbage, nori (dried laver seaweed), onions, bean sprouts, hechima (sponge gourd), soybeans, purple sweet potato, and sweet peppers. This diet also provides plenty of calcium, such as from tofu, an essential element of sound health. Moreover, the frequent drinking of tea, in a relaxed manner, aids digestion, metabolizes fat, and increases flavonoids. Widespread use of turmeric and ukon (Curcuma longa), along with a general reluctance to take Western-type drugs (unless they are herb-based), are also of relevance--especially considering that prescribed medications are now in fact one of the leading causes of death in many countries.

Likewise, the extremely low incidence of dementia in older Okinawans, compared to that in the West, has been linked to the drastic difference in the amount of refined sugar ingested. Moreover, as Dr. Sanjay Gupta emphasizes in his book Keep Sharp: Build a Better Brain at Any Age (2021), "the most important thing we can do to enhance brain function and resiliency is exercise--as in, move more and keep a regular physical routine." Frequent, lifelong physical exercise is an essential element of the traditional Okinawan way of life. Gupta points out that neurogenesis, the production of new neurons in our brain, can occur even when we are very old--if we provide the stimuli.

Reflecting the frequent research finding that connection with others is a vital factor in healthful aging--while isolation is a strongly negative factor--the moai social system of small groups of people who meet regularly, often throughout their lives, providing mutual support and combining practical physical help with companionship, is an ancient Okinawan community structure. These groups offer support of all kinds, including spiritual and financial, as needed. As for other factors, long working lives, frequent laughter, and positive mindsets were all the norm in the Okinawan islands of olden times. The abundant sunshine there, with its resulting high amounts of Vitamin D, is likely to be an element that supports good health, as numerous studies have found. These fruit- and vegetable-loving islanders also surely have a high intake of beneficial Vitamin C. Smoking is inadvisable if you seek longevity, but alcohol in moderation does not appear to be problematic. Indeed, many centenarians throughout the world, including in the Ryukyus, have a small daily tipple. The respect that older people traditionally received in Japan is certainly supportive.

Data and examples like these should positively influence public health schemes, local community support systems, and the dietary behaviors of schoolchildren.

What Can We Learn?

JY: What can we learn from the traditional Okinawan way of life, to improve our own life experience?

GM: This is an excellent question for our times. Indeed, it goes well beyond the confines of "our own life experience"; it is relevant to today's world. These days, with the extended office working hours, compounded by often long commuting hours and the "work from home" modus operandi that exploded in many work situations during the recently faded age of Covid-19, the traditional Okinawan life- and work-style offers a much-needed message.

Today, we witness work-related behavior called "lie-flat" appearing in China and even in Vietnam. This mindset emphasizes a minimalist approach to work, avoidance of involvement, and seeking meaning and purpose in life from interests outside the office. I have read of reports from Japan too where even millennials--young people born after 2000--are seeking alternatives to 10-hour working days and seeking solitude and sanity in depopulated Japanese rural villages, including in Okinawa--where, often, low-cost housing can be easily found. Concomitant with this trend and rediscovery of meaning in life and work, is the rediscovery of the causes of both mental and physiological illness. Clearly, aspects of the traditional Okinawan lifestyle and philosophy of life and work are very relevant here.

It is likely that the instant communication technologies such as Whats App and incompletely contemplated messages have become an explosion in electronic messaging. Many people are on overload. This overload contributes to substandard thought. The notion that time for thought is vital, precious and oh so very human tends to be lost in a tsunami of e-messaging. Life becomes a race fed by an almost endless flood of instant and inadequately conceived partial messages. Sending any Whats App has too often replaced voice to voice and thoughtful exchanges and problem solving.

JY: The last few years in particular have brought about much divisiveness and polarization in the world. Do you have any suggestions on how we can heal these rifts?

GM: Your question about what we can learn (or, better, re-learn) from the traditional Okinawan way of life and how the divisiveness or polarization that pollutes our mental health can be reduced, leads us to another issue of our times, the ongoing, relevant issue of education. Earlier in this interview we mentioned the wisdom of reaffirming and promoting the many values of the Okinawan diet and lifestyle. The knowledge on which the Okinawan traditional teachings are based has a valuable message for schools and daily life and work. To enhance community health--at all ages and stages--through applying the Okinawan wisdom could help us in Japan and in so-called "developed" economies to make a better "work-life balance" become the new norm. One hugely welcome further outcome of such a rediscovery would be the resulting tremendous savings in public health costs. Another equally welcome positive result would be the enhanced productivity in schools and offices that comes with positive feeling--with omoro in action.

May the "land of happy immortals" teach the world how to stay sharp, keep strong, and spread happiness.

Japan SPOTLIGHT January/February 2024 Issue (Published on January 10, 2024)

(2024/01/16)

Jillian Yorke

Jillian Yorke is a translator, writer and editor who lived in Japan for many years and is now based in New Zealand, where she is the curator of the Japan Library: Pukapuka.

Japan SPOTLIGHT

- Coffee Cultures of Japan & India

- 2025/01/27